(An attempt to synthesise the results of discussions held between the 3rd and 8th July, 1978)

Preface

This report was published in the Bulletin of the Communist Platform, No. 2, June–September 1978, and is an attempt to present the discussions of two socialist feminist workshops held in Bombay (a smaller,more theoretical Marxist discussion from 3 to 5 July, and a bigger discussion including a larger number of women activists from 6 to 8 July) in a coherent manner. It therefore involves some selectiveness in what is reported and what is not, which undoubtedly was influenced by our own standpoint.

We may not now agree with every word we wrote then, but looking back at it after a period of more than 40 years, one thing that strikes us is our prescience in identifying sexual assault as a major issue, and in attempting to accommodate it within a revolutionary socialist perspective. A new wave of the Indian women’s movement emerged after the Supreme Court in 1979 reversed a decision of the Bombay High Court and acquitted two policemen accused of raping a minor Adivasi (indigenous) girl, Mathura. Autonomous feminist groups were formed and erupted in protest up and down the country, and they continued to organise on various issues, particularly violence against women, with large-scale protest actions, sustained campaigns in support of victims, demands for legal action against perpetrators, and proposals for reformulation of patriarchal laws. We were involved in the earliest groups, the ‘Forum Against Rape’ – later renamed the ‘Forum Against Oppression of Women’ – in Bombay, and Stree Sangharsh and Saheli in Delhi. These groups were broadly socialist, but independent of political parties, including left parties.

However, this mass upsurge of women after the Supreme Court decision in the Mathura rape case also showed how short-sighted we had been at the time of our workshops in opining that large-scale feminist struggles might not arise in India. The Indian women’s movement surged ahead in subsequent decades, along with an upsurge in movements based on identity politics.

Secondly, we can identify an intersectional analysis (although of course we did not use the word), which sees gender and class oppression under capitalism as coming from different roots and producing a form of oppression of proletarian women that was different from the oppression of working-class men as well as upper-class women. This reflection was triggered by our experience in socialist groups where the ‘women’s question’ was seen only in relation to capitalism, ignoring the connected but independent structure of patriarchal oppression. By contrast with the mechanical materialist understanding of the Communist parties of that time, we were trying to develop a phenomenological understanding of the roots of women’s oppression, and to identify the intersection between gender oppression and class oppression in order to develop the elements of a socialist feminist perspective drawn from the experience of working-class women.

This also entailed going beyond the liberal, existentialist and radical feminist theories circulating at that time. In exploring the difference between bourgeois feminism and proletarian feminism, we discussed the issue of unwaged domestic labour and the daily and generational reproduction of the labour force, linking it with the reproduction of the capitalist system as a whole. The idea that men should share domestic labour so that more women can participate in wage-labour has been almost mainstreamed now, but the redistribution of resources to deal with class inequalities is not on the agenda. On the contrary, the effects of economic crisis for working-class women includes hidden costs in the form of an increase in the time spent in invisible labour: a reproductive tax paid by working-class women to sustain households in the face of cuts to the public sector, privatisation of public services, and macro-economic policies based on the assumption that the time women spend to sustain their families and the economy is infinitely elastic. The commodification of biological reproduction through the emergence of global birth markets and the renting out of wombs by poor women in the South raises further questions for a socialist-feminist perspective.

The question of what goes on in working-class households continues to be a matter of debate among Marxists, with some still holding that it is only a site of individual consumption and not of production, others holding that there is production of use-values but not of exchange-value within such households, and yet others arguing that both use-values and exchange-value are produced in them. We also tried to understand the complexity of the struggle of proletarian women trying to preserve a concern for personal relationships of mutual recognition and love, and how this needs to become a part of the working-class struggle rather than being seen as contradicting it.

What we – and the autonomous feminist groups that were formed in the 1980s – did not take up initially were the multiple intersecting axes of oppression affecting women from Dalit, Adivasi and minority ethno-religious communities as well as LGBT+ communities These were subsequently taken up self-reflexively and in action by members of autonomous feminist groups, albeit unevenly and not always to the satisfaction of the oppressed groups, and the debate continues even today.

The Indian women’s movement and the upsurge of movements based on identity politics have raised crucial issues, but at the same time there has been a shift away from class, with a narrow focus only on gender and other identities in analysis and action. This makes it all the more important to bring back and broaden the question we tried to tackle when we examined the interaction between class and gender. With right-wing ideologies relentlessly gaining strength, the need to identify the linkages as well as the contradictions between capitalism, patriarchy, heteronormativity, and caste and ethno-religious dominance becomes imperative.

Many of the issues we identified as requiring further research and analysis were ones we worked on in the following years and decades. In that sense, these workshops can be seen as setting out an agenda.

Amrita Chhachhi and Rohini Hensman, September 2020

***

Introduction

What is a revolutionary perspective for women? This is a question which communists have by and large evaded in one way or another. The most common mode of evasion is to say that the oppression of women is inevitable in capitalist society and can only be abolished when that society is overthrown. The conclusion: all efforts must be directed towards the overthrow of capitalist society, and women must be drawn into this effort wherever possible, or at least prevented from hindering it. Why this is an evasion is that it ignores the way in which the oppression of women is itself an obstacle to the overthrow of capitalism and why, therefore, a struggle against this oppression is an integral part of the struggle against capitalism. If the latter standpoint is accepted, then the elaboration of a revolutionary perspective for women can be seen to be a necessary task of communists. These discussions were an attempt to begin this task. To this end, certain fundamental questions were identified and sought to be answered: What are the roots of the oppression of women? What form does this oppression take in capitalist society? What movements have arisen in opposition to it, and what is the ideal tendency of these movements? What specific form does the oppression of women take in India? Have any movements arisen in opposition to it, and if so, what is their nature? It is out of the answers to these questions that the elements of a perspective would emerge.

The Roots of Oppression

The question we took up as our point of departure was: what are the roots of the oppression of women? The answer, proposed by Engels and subsequently accepted on the Left – that it is a consequence of the development of private property in the means of production – struck us as being inadequate. These roots, we felt, went deeper and originated earlier: the subjugation of women has been a feature of the most primitive and the most modern societies and appears to be rooted in some fundamental characteristic of the human race. What could this be?

One possible answer which was discussed was that this characteristic is the basic biological difference that makes it possible for a man to rape while a woman cannot. The implications of this can be drawn out by a comparison between human and animal sexuality. In animals, sexuality is linked with reproduction; likewise in human beings. But, in animals, a merely biological relationship is involved, while, in human beings, it is a human relationship. This means that, on one side, the relationship can rise far above what is possible for animals, to love; but, on the other side, it can also be degraded to a sub-animal level, to the forcible violation of another’s person, to rape. On one side complete mutual affirmation of each other; on the other, self-affirmation as the total negation of the other’s humanity, the reduction of the other to a passive object.

But the mere possibility of rape is not sufficient to account for itsoccurrence. The latter needs to be explained by the universal human desire for recognition. This can perhaps best be explained by an elaboration of Susan Brownmiller’s metaphysical parable in terms of Hegel’s Master/Slave dialectic. The primordial fight occurs not between a man and another man, but between a woman who rejects a man as mate and a man who tries to compel her to accept him. He seeks recognition of himself as a desirable partner, but can gain it only by negating her autonomy, which gives her the right to say no. Hence the fight, in which the woman is inevitably defeated, raped, reduced to the status of a thing. Thus, the first class division in society is that between men and women; women as slaves, objects to be possessed, and men as possessors. To begin with, women are ‘public property’, to be possessed, violated at will. It requires a higher development of man’s sense of his own individuality before the idea of permanent possession of women arises. (And, here, surely, language is very revealing. It is said that a man `possesses’ a woman when he sleeps with her; but never vice versa. In this one word is contained the whole idea of woman as a mere thing, a possession.)

What is being argued is not that the subjugation of women arises from some inherent male aggressiveness, but, rather, that this is the primary form in which the man seeks recognition. While the woman, by biological fiat, is compelled to recognise the other’s humanity and to depend on his volition as to whether he will recognise her or not, the man is bound by no such requirement. It is important to emphasis that the essential element is the desire for recognition, which here takes the form of domination, of compelling the other to concede recognition and thus of negating the other’s autonomy as a human being. Ultimately, it is a most inadequate form, for the recognition is accorded not by another who is in turn recognised as a human being but by a thing, a slave.

If this is correct, then it becomes much easier to explain why women have, until very recent times, accepted their subordinate status. To be reduced to the status of the possession of one man may constitute a denial of one’s full humanity, but it certainly carries many advantages. As owner, he has obligations as well as rights – first and foremost, the obligation to protect the woman from other predators. On the side of society, too, it is recognised that this woman, by virtue of belonging to one man, cannot be violated at will by others without fear of punishment. Secondly, within this stable set-up, however lop-sided it is, some degree of human affection is possible between the partners, and between them and their children or at least the woman and her children. These are compensations. So, she accepts defeat.

Here we have a situation far more complex that Hegel’s Master/Slave dialectic, some of the premises of which are distinctly dubious, although uncritically accepted by Simone de Beauvoir. To begin with, the assumption that the Slave gives up the fight because of the unwillingness to risk life, while the Master wins because he is prepared to risk his life. Here, on the contrary, the woman gives up precisely because she does not wish to lose what Hegel might call her `honour’, i.e. she does not wish to be subjected to a process of humiliation and dehumanisation worse than death. And secondly, we may question the assumption that to risk one’s life in order to kill, rape, torture, plunder and enslave, as in war – i.e. in order to destroy and degrade life – is really more human than to risk one’s life in order to give, preserve and protect life. For women are certainly capable of fighting to the death, or working and starving themselves to death, to protect the lives of those they love. It appears, at least, that de Beauvoir’s equation of killing withrisk of life is questionable. Yet the real loss of humanity involved for women in acceptance of their subjugation cannot be ignored either; the abandonment of the development of most of their capacities is a devaluation and mutilation of their individualities which produces its own special neuroses and distorted expressions of love – love as possessiveness of husband and children, slavish docility, an attempt to live a vicarious life through the male members of the family.

It is important to stress that we are here talking not about the historical origins but theroots of women’s oppression. In other words, this element underlies all oppression of women up to the present, although the oppression itself may take different forms in different epochs, and in a class society may take different forms for women of different classes. Just as ruling class power embodied in the state is not at all times experienced as naked coercion, the subjugation of women may not for long periods be felt as brutal oppression. Nonetheless, we found this element underlying many more subtle and insidious forms of oppression.

Very early, then, a certain role is allotted to women as a consequence of their biological difference from men. The same biological fact makes them an object of desire, the captive whose desire is desired, and an instrument of production of the most fundamental element of production – labour-power. Around these functions an institution grows up – the family. The second question we asked was: what is the location of the family within a materialist conception of history?

All societies, from the most primitive to the most advanced, must reproduce human life; hence in each society some specific social relations of human reproduction, a specific form of the family, must exist. The reproduction of human life is simultaneously the reproduction of the individuals between whom those relations are formed, and the production of labour-power, which enters as an element into the process of production. In all societies of relative scarcity, and especially in those where labour-power is a dominant element in production, there arises the necessity for social control over women, who are the reproducers of labour-power. It is evident, then, that the social relations of human reproduction, kinship and family relationships, are linked to the social relations of production, and that the form of the family is determined by the relations of production. We concluded that any definition of the mode of production must account for the relations of human reproduction and their link with the relations of production.

The domination of women now becomes a more complex affair. Initially it was undertaken in order to ensure a captive source of recognition for the man’s individuality; but this very act gives him control over the production of labour-power, the most important means of production. This control in turn is a source of social recognition, recognition by society as someone of worth and value. There is a distinction between these two forms of recognition, although they are interdependent. Suppose, for example, that X is an excellent musician, who for some reason suffers a paralysis and can no longer perform. For the public who admired his performances, he may cease to exist; but there is something in his personality, an inner core, which survives this loss, and for someone who loves him ‘for his own sake’ he certainly would not have ceased to exist. Conversely, if his performances have been recorded, he may continue to get social recognition long after he is dead. But someone who loved him can no longer recognise his individuality, because as a person he has ceased to exist. For a living individual, both forms of recognition are essential. Lacking individual recognition in a close personal relationship or relationships, he or she becomes a complex of social attributes – citizen, doctor, athlete, carpenter, mechanic, entertainer or whatever – but without any centre which can integrate these attributes into a single personality. And since consciousness of oneself is dependent on recognition by the other, the self will also be cognised as a disintegrated self. This will inevitably reflect back in a negative fashion on the individual’s contribution to society as a whole. On the other hand, for an individual to express and gain recognition for all his or her capacities within one or a few relationships is impossible; many capacities require a wider social context for expression at all, and lacking this, simply will not develop. An individual deprived of this wider social context will thus likewise be crippled, and the sense of loss of oneself which results from this crippling must inevitably distort and corrode all close personal relationships.

Social recognition is accorded to individuals for some supposed or real contribution to society, and two major forms have existed historically: the performance of labour, which results in the production of a service or a material product; and the ownership of property, which, if separated from labour-power, becomes a condition for the performance of labour. In all societies where labour-power is the dominant element in production, control over its production – i.e. control over women – would be an important source of social recognition and power (e.g. tribal societies where women and grain – means of reproduction and subsistence – were in the control of elders). Here, too, it is important to note, is a different form of achieving recognition through domination: social status as power, control over other human beings.

Once again, where does this leave women? On one side their subordination is necessary in order to guarantee individual or personal recognition to the male half of society; on the other side their subordination is also necessary in order to ensure social control over the production of labour-power as an essential means of production. When these two sides come together, they neatly trap women in a cage. But – and this is an important consideration – it is a gilded cage. So long as she produces children to the required extent and in the required manner, so long as she single-mindedly recognises the man she has accepted as her Lord and Master, so long as she cares for and looks after the whole family, she is adulated and idealised as the repository of all virtue and honour, goodness and beauty, the conscience of society, selfless devotion, and so on and so forth. Even though this hardly counts as recognition of her individuality, it is still better than nothing. Challenge this role, however, and she runs the risk of the most brutal punishment – being burned as a witch, perhaps, or gang-raped, a form of punishment which we found has been used both in the most primitive tribal societies and in contemporary capitalist societies.

It is not surprising, then, that most women do not challenge; they accept the role, and the necessary crippling of their capacities and personalities that goes with it. An example of this is the vast number of love-poems written by men to women extolling their beauty, goodness, etc. and the relatively insignificant number of such poems written by women to men, although love is supposed to be their sole end and aim in life. The point is that a love-poem, although addressed to an individual, is a social form of expression; and women, although they are expected to express love in their person, are not encouraged to express themselves in a wider social context. Their creativity must adapt and limit itself to expression within the confines of the family. This exposes the admiration they are accorded as admiration for some treasured article of property like a fine work of art. The relationship of possession in marriage is once again underlined in the fact that marital rape is not considered to be a possibility: clearly, one cannot steal one’s own property.

Oppression under Capitalism and the Feminist Movement

The fundamental relation of production of bourgeois society is that between the bourgeoisie and proletariat. The relations of reproduction must therefore reproduce these two basic classes; that is, they must produce human individuals belonging to these classes, and therefore constitute a system of human relationships within which they can be produced. (For the moment, we left out of consideration intermediate and disintegrating strata.) This, then, is the function of the family in bourgeois society. This discussion raised many questions. Two basic questions seem to be involved. (1) What is the adequate form of the family in the capitalist mode of production? (2) Is it identical in the bourgeoisie and the proletariat?

The bourgeoisie, according to the Communist Manifesto, tears away the sentimental veil from the family, and reduces all relationships to relations of cash. In tearing away the individual from all bonds of a communal nature, capitalism does not spare the family community; the war of each against all of bourgeois society is the war of the lone individual against all other lone individuals. All relationships are mediated through the universal mediator, money; and all individuals, relating to one another and to society through money, are equal. The ideal tendency of bourgeois relations of reproduction, therefore, is towards the destruction of all sentiment within such relationships and their reduction to the exchange of equivalent for equivalent. i.e. sex for sex or sex for money. Children are the heaviest losers in this system; having nothing of value to exchange, and no means of struggling for their own individual interests, they are inevitably pushed to the margins of society, and only tolerated even there because they perpetuate the race. A magnified and more comprehensive boarding-school system would perhaps be the most adequate form of bourgeois child-upbringing. As for the principle of inheritance, the inheritance of power was already being challenged by bourgeois thought in the eighteenth century, and there is no reason to believe that the inheritance of property by relatives is an absolute necessity in a world of share capital and public property; at any rate, the perpetuation of capitalist property can easily be conceived of even without such a system. Conversely, property itself is often an agency in breaking bonds of sentiment within the bourgeois family (one need only think of the bitter struggles over property which are well known to occur within such families).

Obviously, the existence of such relationships on a large scale in their extreme individualistic form is unthinkable. This is because social relations of reproduction are also human relations, relations within which human beings seek recognition of their value as individuals. There is surely a contradiction inherent in bourgeois individualism: individuality is sought to be expressed in the form of individualism, which is precisely a form in which it can never be realised because it negates the other, whose recognition is the condition of self-consciousness, consciousness of one’s own individuality. Yet this tendency is perhaps what is at work in the progressive dissolution of all community ties, including those of the family, in bourgeois society. At least, we can question the idea that the nuclear family is the adequate form of the bourgeois family.

In the proletarian family, it was agreed, there existed the material basis for superior human relations in the absence of property and the constant struggle against capitalist exploitation; but how exactly these manifested themselves was not clear. One thing seems to be apparent: that the relations in a proletarian family cannot be relations of competition, of a war between the individuals in it. The very survival of the proletariat depends on the limiting of competition within it, and this is more than a formal matter: a sense of solidarity and comradeship is an essential emotional condition for the proletarian struggle. If these were to be eroded at their most vital point, the results could be drastic. This is perhaps the source of the violent opposition initially offered by male workers to the entry of female workers into the labour-force as competitors with them on the labour market, thus bringing competition into the family itself. This opposition takes a reactionary form at first; but the impulse behind it is as much a resistance to the break-up of human relationships that offer some emotional sustenance as an effort by the men to preserve a hierarchical family structure. If only the latter element were involved, it would be impossible to explain why proletarianwomen also seek to perpetuate the family, sometimes going through struggle and hardship in order to do so. They would not so easily become deluded victims of ‘bourgeois ideology’ unless it in some way, however inadequately, met their own needs. When we discussed this question it became apparent that in withdrawing from the wage-labour force, women workers were not merely a passive object of technological change, pressure from their menfolk or bourgeois ideology; rather that this, like absenteeism, was a form of protest against the alienation of factory labour, the extra burden it constitutes for them, as well as a positive assertion of their concern for their children’s welfare. The major factor seemed to be that in housework, however backbreaking, protracted, boring and isolated the work itself, they could see the products of their labour doing some good to people they cared about, instead of being sold on an impersonal market for the profit of an oppressive employer.

In fact, an examination of the history of the working class shows that it was the bourgeoisie who uprooted and tore apart the proletarian family, and the proletarians, both male and female, who won it back through struggle. Having been forced to concede it, as they were forced to concede trade unions, the bourgeoisies then proceeded to make use of the family, as it also made use of the trade unions, as a means of controlling the working-class struggle. Perhaps they did even more. It is possible that it used the form of the family won by the proletariat as a model for its own relations of reproduction. The nuclear family would then be a much more complex phenomenon than simply the bourgeois form of the family. It would be the form of the family won by the proletariat under conditions of capitalist production (e.g. mobility of labour-power), and then incorporated and institutionalised by bourgeois society. It would be an example of the way in which the proletariat, even though as yet incapable of achieving a revolutionary transformation of society, nonetheless acts as a subject of history, leaving its mark on bourgeois society even while it is shaped by that society.

The family in capitalist society has a measure of stability inasmuch as it reproduces the classes of that society and provides personal recognition for one half (the male half) of the society. But it comes under attack long before capitalist relations of production themselves begin to disintegrate. This attack has come from the feminist movement, whose birth takes place under capitalism. Why?

This question we could not adequately answer, although some tentative ideas were put forward. The development of the productive forces under capitalism has two important consequences for women. Firstly, the development of effective methods of birth control, which has released them from almost continuous childbearing throughout their years of maximum activity. With this has come the recognition that a condition which appeared to be natural, ordained by God, is in fact a matter of human choice. With the possibility of control over their own bodies in this area has come the demand for such control, which no amount of religious bigotry has succeeded in stopping. With the greater part of their lives freed from childbearing, the idea that this alone is the natural function of women ceases to have any material basis.

Simultaneously the enormous development of the productivity of labour under capitalism for the first time makes labour-power a subordinate element of production. As the creator of surplus-value it of course still plays a crucial role; but in terms of quantity, the need for it diminishes with each technological advance. After the major periods of primitive accumulation are over, there is not so much a shortage of labour-power as a surfeit of it: the necessity for social control over reproduction in order to ensure an adequate supply of labour-power disappears. Just when women become capable of controlling their reproductive functions, society ceases to need to compel them to do otherwise. Conversely, the periodic necessity for capitalism, especially in the early stages, to incorporate large masses of women into the wage-labour force undermines from another side the idea that the role of women is exclusively in the sphere of reproduction. In these developments, perhaps, can be found the material basis for the development of the feminist movement.

The feminist movement is directed against the inadequacies of bourgeois social relations of reproduction; but it attacks these from different standpoints. There was a problem in identifying different currents within the feminist movement. If the criterion used is the method of struggle, the main divisions appear to be between an individual, existential mode of struggle through an attempt to create new types of personal relationships, and a political mode of struggle. Alternatively, if the criterion is thegoal of the struggle, then the main distinction would be between bourgeois and socialist goals, and within these there could be attempts to change relationships between individuals as well as attempts to change relationships between or within social classes. If we provisionally adopt the latter, we could tentatively divide the feminist movement into two major currents – revolutionary and bourgeois – although in any movement both currents may be closely intertwined.

Bourgeois feminism which adopts political methods is aimed mainly at the achievement of equality of women within bourgeois society. Its major demands have been that women should have equal political rights (right to vote and stand for election), equal rights to the ownership of property (and thus also to the exploitation of the labour-power of others), right to work and equal wages (i.e. the right to sell one’s labour-power and be exploited to the same extent as men), and equal opportunities for getting an education, jobs, etc. It appeared that this movement could both advance andhinder the achievement of socialist goals and the interests of women. For example, the right to employment and the right to vote could result in the growth of confidence, consciousness and self-activity amongst women; but the right to equal exploitation, which meant abandoning demands for special protection for female labour, and the right to serve the nation and make equal sacrifices for it in time for war, injured the interests of the working class as a whole, and especially the female portion of it. Assessing this current from the standpoint of the total emancipation of women is therefore a complex matter; one cannot simply write off the movement as bourgeois and therefore useless, nor can one adopt a simple stageist view that it necessarily precedes and leads to the further development of a revolutionary feminist movement.

The existentialist attempts to achieve the same goal have ranged from Simone de Beauvoir-type attempts to discover new forms of relationships between individuals (no marriage, no children), to the extreme solutions of radical feminists like Shulamith Firestone, who see the solution in the complete cutting-off of stable human relations between men and women, reproduction and childcare reduced to purely technical functions, and so on. Here, the problem that is sought to be resolved is the crippling of the individuality of women which inevitably occurs under the existing system of relationships. But the solution is seen in terms of female individualism which is opposed to male individualism. As in the case of bourgeois feminism which takes a political form, the premises of bourgeois relationships are taken for granted, so that equality is the equality to compete; in the bourgeois war of each against all, it is assumed that the assertion of individuality must be at the expense of other individuals. The inevitable conclusion must be sex war.

A thorough analysis of these movements would be necessary before any definitive evaluation of them can be made. But it appears that from such a standpoint the emancipation of women can never be achieved. For, if the problem is one of recognition, then the achievement of a competitive equality is no solution. Women may achieve the same degree of social recognition as men – which is in any case very limited for the vast majority – but by refusing to concede personal recognition to men, they do not thereby gain it for themselves. At best, they can return to an original state where institutionalized forms of domination have been eliminated and only brute force can subjugate them. This is perhaps the condition that exists in America, where equality for women has progressed far, women form almost half of the labour force, millions of women beat their husbands, and yet women are daily subjected to the most brutal assaults. However much they arm themselves against such assaults, the threat of them must always be there, and with it the danger of being overcome by superior force.

Thus, two criticisms can tentatively be made of bourgeois feminism. Firstly, that its tendency is towards pure individualism, and, in this direction, there can be no solution to the problem of recognition, neither social nor personal, which we found to be at the root of the oppression of women. Secondly, that it still views the problem from the standpoint of a concealed male chauvinism. The effort is directed towards making women the same as men; in this effort it is overlooked that some of the values that go into the definition of `masculinity’ may well need to be rejected by men and women alike (e.g. aggressiveness, competitive individualism); likewise, that some of the values which are supposed to be `feminine’ are in fact human qualities which should be common to both men and women. Thus, they negate the contribution which women can make and have made to human culture. The love of children, for example. Marx once said that he could forgive Christianity all its sins because of the love of children which it introduced into human culture. But to this day, this is by and large considered to be a feminine attribute. To assert it as a human quality is to acknowledge one aspect of the contribution women have, despite tremendous disadvantages, made to human culture. To seek to eliminate it from women and from human culture is implicitly to accept the values of a male-dominated, achievement-oriented, commodity society, where human qualities which neither win fame nor make money are considered to be inferior or useless. Only on some such assumption could radical feminists characterise child-rearing asanimal activity – presumably implying that children are little animals who could just as well be brought up in menageries. Paradoxically, then, this current of feminism asserts that women can become human only by ceasing to be women, by rejecting female sexuality, mutilating themselves in a different way, becoming female eunuchs. In its essence it is therefore anti-female and anti-human, and makes no contribution to the abolition of the dehumanised relationships which lie at the root of the oppression of women, but rather takes them to their logical conclusion.

The movements which have grown up around the demand for abortion, protests against rape and wife-beating, demands for the recognition of the social importance of housework, are potentially revolutionary although revolutionary goals may not explicitly be stated. The demand for abortion, although it may itself be met within bourgeois society, is in fact an assertion of the right to control one’s own body, which in bourgeois society is constantly violated, sometimes systematically and outrageously as in the case of torture and rape (which we felt were closely linked) perpetrated through the state (police and army). Thus all these demands – free abortion, no rape, no wife-beating – point towards a system of human relationships free from coercion and domination even if this aim is not consciously articulated.

The Proletariat and Feminism

The recent importance being given by Marxists to the significance of housework perhaps expresses an increasing opposition on the part of working-class housewives to this specific form of oppression. Although this cannot be seen as the root of their oppression, yet it is an important form in which oppression is experienced, as well as constituting the material link in bourgeois society between relations of production and relations of reproduction, and hence clarification of the relations involved is a necessary task for Marxists. The socially necessary and value-creating character of housework establishes on a scientific basis the roots of this domestic slavery in capitalist production relations; and the demand for wages for housework, however we assess it, at least expresses an awareness that this is a social problem which cannot be resolved on an atomised basis (e.g. sharing of housework between men and women). The question as to why so many processes of production closely connected with reproduction have remained unsocialised was not resolved, although it was pointed out that partial socialisation has taken place – e.g. schools, laundries, processed foods etc. An answer may lie in the large portion of unpaid labour which can be concealed in housework, as well as the necessarily labour-intensive nature of the work involved. Both of these factors, as Marx pointed out inCapital, make it less profitable for capitalists to produce the same goods and services by means of wage-labour engaged in large-scale production. If this is the case, the demand formore wages for housework (forsome wages are already provided in means of subsistence) may be one of the most effective means of obtaining socialisation of housework, since the history of trade unionism has shown that an increase in wages is one of the major motive forces pushing capitalists to rationalise production. But the question remains: how would it be possible to fight for such a demand or related demands, given the isolated nature of the housewife’s labour?

There are two reasons given for the generally low level of militancy among women, and although they are often assimilated to one another, it is important to distinguish them. One is that the nature of household labour, the fact that it is carried out in isolation, makes it impossible for housewives to develop a collective consciousness or participate in social struggles except as appendages of their menfolk who engage in socialised production. This idea stems from a conception which sees class consciousness as determined by the nature of the labour process. Thus, housewives can achieve only a family consciousness, since their labour is confined to the family; workers can achieve a collective consciousness, but one which is confined to the corporate group to which they belong, the workplace or trade union: thus trade union consciousness, syndicalism. The logical conclusion of this conception, which was asserted by Kautsky and emphatically repeated by Lenin inWhat Is to Be Done, is that the working classcannot, by its own efforts, achieve class consciousness or revolutionary consciousness. It is only the bourgeois intelligentsia, by virtue of its own mental labour-process dealing with abstractions like society, state, production and classes, which can achieve a revolutionary consciousness which they then inject into the proletariat.

This is a fundamentally false conception of class consciousness, which remains at the level of the most superficial determinants of consciousness and fails to comprehend how consciousness develops through the striving to understand struggles whose nature is determined by the totality of social relations and not simply by relations in the workplace. Thus, it is completely unable to explain important periods of working-class history: for example, how it was that one of the most advanced forms of struggle and organisation, the workers’ government, was discovered in 1871 by a Paris proletariat consisting largely of small-scale producers with a significant proportion of women, and without the help of a bourgeois intelligentsia giving them class consciousness from outside.

The other reason commonly given is that women, having the responsibility of maintaining the home due to the sexual division of labour, are emotionally far more vulnerable to the hardships of their children, and therefore unwilling to engage in any action which endangers the family welfare and income. This condition would apply not only to housewives, but also to women workers, and appears far more plausible than the first reason. We have reason to believe, for example, that where women are unwilling to go on strike, or to let their husbands go on strike, or act as strike-breakers, the reason is their commitment to the family’s welfare. Likewise, the extent to which they drive themselves on a piece-rate system, sometimes competitively excluding casual workers in the process, is also a function of devotion to their families. They thus act in the interests of a corporate group – the family – without taking into account the interests of the class as a whole, just as for long periods the workers struggle for the interests of a wider corporate group (based on workplace, industry, etc.) without taking into account the interests of the class as a whole. In both cases there is an adaptation to bourgeois individualism, inasmuch as competition between these sub-communities within the working class continues to occur; but also an adaptation of individualism to the needs of the working class, inasmuch as competition within these sub-communities is eliminated.

But this is not a static contradiction requiring an external agency (the bourgeois intelligentsia) to break it. Rather, the dynamics of the class struggle itself lead to situations where the apparent contradiction between the interests of particular groups of proletarians and the class as a whole disappears and the entire proletariat is able to constitute itself as a community, a class for itself. And it is surely not accidental that it is in such periods that women have been most active, shown the greatest initiative and courage in struggle. At any rate, one of our tasks would be to study such situations from the standpoint not of a theory of class consciousness which views the proletariat as a passive object of bourgeois ideology, but a theory which conceives of the proletariat, including the female portion of it, as conscious subjects struggling to define and achieve their historical tasks.

From this standpoint, the struggle of proletarian women to protect the interests of their families takes on an entirely different significance; it is implicitly a struggle to preserve a concern for personal relationships, the love of children, mutual recognition and love, even if it takes on the appearance of passivity, docility or conservatism; it is therefore not to be negated, buttranscended and thuspreserved in the wider struggle for socialism. Without this contribution, socialism would appear as a society of socialised production in which there is comradeship and solidarity but no love: social recognition for the capacities of an individual, but no recognition for the individual’s personality as an integrated totality. This is probably the way in which socialism is conceived of by most proletarian women, which is why, possibly, they show little or no interest in struggling for it. The way in which collective struggles in their place of residence (against extortionate rents, eviction, neighbourhood rape, etc.) as well as attempts at cooperation and mutual aid begins to develop a collective consciousness in proletarian housewives, which is then further developed as these struggles mesh in with more generalised social struggles – this is a process which has not received even a fraction of the attention it requires. Such a study is necessary in order to understand why certain forms of organisation and struggle – e.g. trade unionism – have by and large received little interest from women, and to identify what forms of organisation and strugglecan fully involve them and historically have done so – e.g. the Commune, street committees, soviets, etc.

It is from this standpoint – the standpoint of the proletariat as a conscious subject struggling to constitute itself as a class – that the importance of specifically feminist struggles within the working class (e.g. against wife-beating, rape, the commercial use of the female body, etc.) can be gauged. For the working-class family is the sphere where wage-labourers are produced – i.e. not a thing, labour-power, but living individuals in which this labouring capacity is embodied. Hence it is important not only that a mere capacity to labour be reproduced, but that living individuals prepared to accept the system of wage-labour, of factory discipline, of enforced production of surplus value, be reproduced. And here the bourgeoisie has scored a success. Just as it was able to make use of trade unions to limit the class struggle after earlier having been forced to concede the right of combination, it has been able to use the proletarian family, won from it by bitter struggle, as a breeding place for `good’ proletarians. The hierarchical structure which still exists in proletarian families – not merely because they are dominated by bourgeois ideology, but because the basis for this adaptation to bourgeois ideology exists in the continued search for recognition as domination – reproduces in the most intimate sphere of life the fundamental features of class society. Children who daily see their father giving orders to their mother, who see their father beating their mother and are themselves ill-treated, perhaps by both parents, can only grow up accepting it as a ‘fact of life’ that human society is inherently hierarchically structured with those above having the right to use and abuse those below them. The authoritarianism of factory and state becomes far more easily acceptable if authoritarianism is seen as an essential element of human relationships as such, and the reduction of human beings to mere embodiments of the commodity labour-power is so much the more credible when they see women being treated as possessions, use-values, objects, commodities, in their own homes and in society at large.

It follows that the acceptance by women of the present situation is a condition for the stability of the capitalist system, while struggles against these forms of oppression in fact strike at the roots of the reproduction of capitalist relations of production and reproduction. As Marx pointed out in relation to the English and Irish workers, it is inconceivable that the proletariat could overthrow the class domination of the bourgeoisie unless it has first eliminated all relationships of domination and subordination within its own ranks. Another way of putting this is to say that the constitution of the proletariat as a human community is the condition of its revolutionary success. So long as proletarians collaborate in suppressing the development of the capacities of other proletarians, they put obstacles in the way of these others participating in the class struggle and thus constituting working class solidarity. At the same time, they dehumanise themselves and thus render themselves less capable of struggling against the dehumanisation of bourgeois society. One example of this is the demoralising effect on themselves of the acts of rape and other atrocities committed by the Red Army in Germany. Another is surely wife-beating in the working class and other forms of male chauvinism, even if they are concealed under the cover of revolutionary phraseology. As Engels correctly remarked, in such families the man is the bourgeois, the woman the proletarian. The worker first has to fight the bourgeois in himself if he is to be successful in fighting the bourgeois class. Male chauvinism in the working class, like chauvinism in the working class, is a form in which bourgeois ideology enters the proletariat and dominates it.

The solution to the corporate (family) consciousness of the housewife cannot be the counterposition of another corporate interest (say, that of the factory or trade union), but, rather, itssubsumption into a wider class interest which does not oppose but preserves the interest of the family and especially of the children who may not be capable of directly fighting for their own interests. Where such a class interest is not constituted, hostility and suspicion between competing corporate groups, or mutual indifference, can arise. But it is important to understand that this is a contradiction inreality, and not merely a consequence of the backwardness or illusions of the women.

Thus the socialist-feminist struggle against dehumanised human relationships, against recognition as domination and for recognition as mutual affirmation, is an integral part of the struggle for socialism, a part without which that struggle cannot be successful; it is also a necessary struggle in the sense that male domination within the working class and passive female acceptance of it come directly into conflict with the tendency of the working-class struggle, which increasingly demands the solidarity, unity and active participation of the whole class. At the same time, the ultimate emancipation of women cannot be achieved without the abolition of the division of labour and the achievement of communist production, which will allow the full development of the capacities of men and women alike and accord them social recognition, at the same time abolishing class domination, one of whose forms of expression is the rape and torture of the dominated class.

The possibility of free expression of all capacities in socialist production and of social recognition of the individuality expressed in those capacities will eliminate the crippling effect of both domestic slavery and wage slavery, which is largely responsible for the morbid possessiveness in human relationships which is sought as a substitute. In a society where social recognition is gained not at the expense of others – through competition and domination – but through cooperation and mutual affirmation, any attempt to gain personal recognition through coercion, limiting or robbing the autonomy of the other, would be a contradiction. In bourgeois society, self-affirmation, both in social and in personal relationships, is necessarily at the expense of the other; in personal relations, self-affirmation of the man takes the form of egoism, negation of the other, while affirmation of the other by the woman takes the form of self-sacrifice, negation of the self; in society, self-affirmation takes the form of eliminating others from the competitive struggle, while the only affirmation of the other which is at all possible is the involuntary withdrawal from competition after a defeat – e.g. ‘one capitalist always kills many’. The proletarian struggle is directed against this principle in both personal and social relationships, and thus the revolutionary proletariat, which struggles to build a communist society, is the agent of the emancipation of women, and the women within it acquire an especially important role. This much at least can be said, although to attempt any further specification of the form which human relationships will take in a future society is difficult. Some such attempt, however, has to be made, since it is the task of communists to anticipate – not only in theory but also in practice – the relations of a society which has yet to be built.

Women in India

A very brief examination of the condition of proletarian women in India indicated that, in terms of living standards and hours and conditions of work, they were not far from the level to which women had been reduced by the onset of the industrial revolution; however that this degree of exploitation occurs in the context of an advanced capitalist world economy where it plays a specific function. The part played by the intensive and extensive exploitation not only of wage-labour but also of household labour in reducing the value and price of labour-power is an important element in the development of capitalism in India and needs to be further investigated. Here the relevance of establishing the social character of proletarian housework is once again felt, for unless household labour as well as wage-labour is included in the calculation of the working day, the true extent of the exploitation of female labour cannot be grasped.

Another peculiarity was the persistence of family relations characteristic of an earlier mode of production which, although breaking down, have not entirely disappeared. Again, the possibility that because this breakdown occurs not in a period of early capitalism but in the context of an advanced capitalist world economy, it could lead to a stabilisation of certain intermediate forms, cannot be discounted; at least, it is clear that the process of breakdown and reconstitution of the family does not take place in the same form as in Europe.

Conversely, however, bourgeois rights (the right to vote, etc.) have been granted to women in India without a struggle of their own, as a by-product of the struggle for bourgeois rights in other countries. These circumstances may account for the fact that a feminist movement such as arose in Europe and America has never arisen in India, and perhaps may never arise on a large scale; struggles of a bourgeois-democratic character have been short-lived and have never acquired a mass following. Thus, a situation exists in which an extremely high degree of exploitation of female labour-power is underpinned by social relations of reproduction which make it almost impossible for women to struggle effectively without risking social ostracism or worse. At the same time, there is strong pressure on them to participate in working-class struggles in order to make them more effective, and this pressure particularly comes to the fore at times of intensive working-class struggle. At such periods, then, these women would be subject to painfully contradictory pressures: between, on the one hand, their conception of themselves and their role in society, which has been instilled into them since childhood and which is reinforced by real concern for their families, and, on the other hand, the militant role they are expected to play on demand, which implies a sacrifice of family interest. A crisis of identity results; since the self is cognised only in relation to the other, the contradictory conceptions of herself which a woman is here presented with must lead to a questioning of her own identity. While this may be a creative contradiction if she is able to discover an identity in a higher level of self-activity than is involved in the role of either home-maker or manipulated support for some outside struggle, it can also be a painful and disorienting experience if such a solution is not found. It is also important to note that this is not a contradiction between individualism and class consciousness; for family consciousness is a form of corporate consciousness which in India often leads to an almost total negation of the interests of the woman, while the alternative that is posed by militant struggle, so long as it opposed to the interests of women and children, is not yet a class interest either, since it is not the interest of the proletariat as awhole. What the exact effect this contradiction has on the consciousness of women; how this can be resolved; whether struggles have occurred in which women have discovered ways and means of transcending their family interest without negating it, and simultaneously achieved a higher degree of self-identity and self-activity; if so, what form these struggles have taken, and what forms of organisation they have been embodied in -all these questions require answers in order that a systematic perspective be built, and they can be answered only through sensitive discussions and involvement with proletarian women and their struggles.

Conclusions

It is evident that these discussions posed many questions, most of which were answered only very tentatively or not at all. Yet they indicated that the problem of women’s oppression and hence the solution to it is a far more complex one than simply a matter of ‘equality’ and ‘economic independence’. Inequality and economic dependence on males are not the cause of oppression, but merely forms in which that oppression is manifested; the roots of oppression lie much deeper, and unless they are discovered and destroyed, the oppression of women will continue despite full employment and formal equality. At the same time, the forms of struggle and organisation through which women can fight for their emancipation, the transitional steps they must take, the relation of their struggle to that of other oppressed and exploited groups and to the working-class struggle as a whole – all these have to be determined far more concretely than they have been hitherto. Otherwise the assertion that the emancipation of women is inseparable from the socialist revolution remains a mere idea whose truth cannot be proved in practice. The process of resolving these questions is nothing but the elaboration of a revolutionary perspective for women.

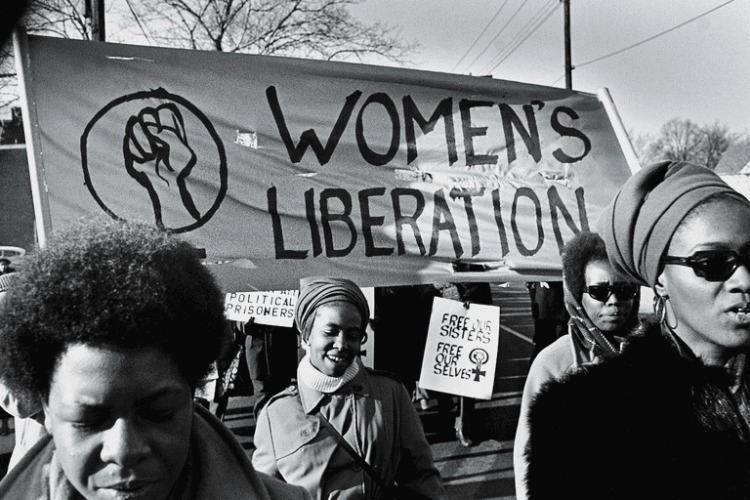

Photo by Linda Napikoski – https://www.thoughtco.com/1960s-feminism-timeline-3528910, CC BY-SA 4.0,https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=78053903