Sara R Farris on Elena Ferrante.

Main photo: Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909, USA. Mary Dreier, Ida Rauh, Helen Marot, Rena Borky, Yetta Raff, and Mary Effers

Sara R. Farris is a Senior Lecturer in Sociology at Goldsmiths College, University of London. She works on sociological and political theory, ‘race’/racism and feminism, migration and gender, with a particular focus on migrant women and their role within social reproduction. She is the author of Max Weber’s Theory of Personality. Individuation, Politics and Orientalism in the Sociology of Religion (Haymarket, 2015), and In the Name of Women’s Rights: The Rise of Femonationalism (Duke University Press, forthcoming in April 2017). She is a longstanding member of theHistorical Materialism Editorial Board. This article was originally published byViewpoint Magazinehere.

“There is no true life, if not in the false one,” is a dictum from Franco Fortini, Italian poet and communist intellectual, of the same generation of Pier Paolo Pasolini, and yet unlike him (by choice and destiny) not as well known internationally.[1] With these words Fortini turned upside down Adorno’s famous line from Minima Moralia, “Es gibt kein richtiges Leben im Falschen,” usually translated into Italian as “Non si dà vita vera nella falsa”: there is no true life in the false one.[2] In that line Adorno seems to argue that it is not possible to conduct an ethical, morally just and true life within an unjust social order. The aspiration to truth and justice, the very possibility of enjoying life fully, requires us to change that social order. Fortini’s claim was no less radical. By turning Adorno’s line into its opposite, Fortini pointed to the fact that what we call truth and authenticity, or ethical life, can and does emerge even in the midst of the falsehood and injustice capitalism brings about. The true life, framed in any purist sense as “stainless,” and authentic experience of oneself and others does not exist. Life, as well as political work, is always a mishmash of true and false, authentic and inauthentic, rational and irrational, revolution and reform. Our “capitalist” life is enmeshed in contradictions; we need to work through them if we wish to attain a more just social order, not as some sort of utopian, happy island, but as the concrete unfolding of our struggles for justice, including the struggles with ourselves. The problem with Adorno’s thesis, Fortini seems to suggest, is that his true life does not appear to leave room for the murky, unsettled, uncanny zone that characterizes our experience in this world – a zone that will not be erased by a more just society.

When I read Elena Ferrante’s justly celebrated works, I could not help but think about Fortini’s words. Ferrante’s quartet, entitled My Brilliant Friend but known in English as the Neapolitan novels, has become a true literary event in both Italy (her home country) and the English-speaking world.[3] In Italy the fourth volume has been recently nominated for the most prestigious literary prize – the Premio Strega – and the entire quartet will soon be turned into a TV series. In the United States, parties were organized to celebrate the release of the English translation of the fourth and last installment of the series. All major literary journals and newspapers have hosted enthusiastic reviews of her books, praising the clarity of her style and the precision of her descriptions of complex emotions. In spite of the different angles from which her work has been judged, the majority of reviewers stress the psychological motives to which Ferrante has been able to give voice, to the extent that she has been nominated as the “master of the unsayable.”

For anyone who has read these novels, it is impossible not to acknowledge that so much of their power lies in the disarming frankness with which Elena Greco – the narrating voice and one of the two main characters – forces the reader to confront the profound inner drives, desires and fears no one has the courage to tell others, or oneself, let alone to phrase in such acute and accurate prose. Ferrante’s chosen register, however, is not limited to the psychological realm. Her novels are not only superb frescoes of the passions, but also windows onto history, condensations of the personal and the social context in which the characters move. History, in this sense, is not inert background, but part and parcel of the biographies of the dramatis personae; all of them are powerfully affected by its unfolding, while also trying themselves to affect history, or what appears to be their seemingly ascribed destiny.

In this essay I will try to convey some of the complexities of Ferrante’s novels by thinking of them as impassioned journeys towards the discovery of the many archives of Italy, as well as of the self. In doing so, I will draw in particular upon one central theme in Ferrante’s works: that of “dissolving margins.” It is this theme, I argue, and the many ways in which Ferrante grapples with it, that makes the Neapolitan novels a testament to the borderline experience between true and false, as categories of both the personal and the political.

A Tale of Two Women

The quartet that begins with L’amica geniale – the title of the first installment as well as of the entire series in Italian – narrates the friendship between two women, Lila and Elena (called “Lenù”). They both grow up in a poor rione (neighborhood) of Naples in the aftermath of World War II. Lila is an apparently fearless, erratic child who scares even older male children with her temper and determination. Lenù is instead a more docile girl and perhaps for this reason, she is disturbed and yet seduced by Lila’s wild manners. Their friendship begins the day Lenù retaliates against Lila’s bullying behavior by throwing Lila’s doll in a dark underground cellar, as Lila had done the same to Lenù’s doll. When the two girls go to find their dolls, they have disappeared; according to Lila, they have been taken by Don Achille, the rione’s boogey-man:

My friendship with Lila began the day we decided to go up the dark stairs that led, step after step, to the door of Don Achille’s apartment.… Don Achille was the ogre of fairy tales, I was absolutely forbidden to go near him, speak to him, look at him, spy on him, I was to act as if neither he nor his family existed (Vol. 1, p. 27).

This apparently trivial episode is key to making sense of Lenù and Lila’s relationship, up until the very last lines of the fourth and final volume. From the loss of the two dolls and the visit to Don Achille onwards, a strong bond of love and hate, dependence and need for autonomy, faith and mistrust will be forged between the two girls. Lenù’s attachment to Lila deepens once she discovers something that troubles and yet excites her. Lila is not only the unruly and unpredictably brave daughter of a shoemaker; she is also extremely intellectually gifted. Lila can read before all other children in her class can; she has an incredibly precocious mind that allows her effortlessly to teach herself anything she is interested in. She is as sharp as a knife, including in her judgments about people’s character, something that seems to alienate her from her peers. Lenù is fascinated and challenged by Lila’s gifted persona to the extent that she will spend the rest of her life attempting to find out the secret of, and trying to emulate, what she regards as Lila’s superior mind. The academic competition between the two girls is interrupted, however, by a story all too common in Southern Italy in the early 1950s. They are both working-class daughters; neither of them is destined to continue her studies after their mandatory five years at the primary school. Their families don’t have the resources to send them to the more demanding secondary school, nor can they afford to lose their labor-power, which is essential for the sustenance of the working-class Southern Italian household. However, while Lila’s family obeys this rule, despite much crying and anger from Lila who wants nothing but to continue her studies, Lenù’s family finally decides to allow their daughter to go to secondary school (thanks to the insistence of her teacher). This event marks the beginning of the many moments of separation/incommunicability/return between the two. Lenù can continue to cultivate her intelligence, to dream of that social mobility they both well understand can be achieved in two ways: either through education, or through marriage with a higher-ranked man. Lenù is allowed to turn down the first path by attending a liceo classico (classical lyceum) and then being awarded a scholarship at the prestigious Scuola Normale di Pisa to study Classics. Lila, on the other hand, will undertake the second road by marrying a well-off shopkeeper from the rione. Lenù will thus manage slowly to subtract herself from the small-minded, poor, and violent environment of the rione, whereas Lila will never be able to do so (Lila will seldom leave the rione for most of her life). And yet, the more successful Lenù – who will end up becoming a famous writer and marrying a respected academic from a well-known Italian Leftist family – will always feel inferior to the uneducated Lila, who instead will leave her husband to become a worker in a meat factory first and then the owner of an accounting company.

Lenù’s personal tale of her friendship with Lila spanning six decades is the story of her coming to terms with the emotional and intellectual debts – both fictitious and real – she feels towards the extravagant, brilliant Lila. But Lenù’s confessional story is also a testimony of post-WWII Italy: a full immersion into its history, politics, mutations and more recent decay. By presenting in front of our eyes the world of unsettled feelings and memories she has built up against, and shared with, Lila, Lenù also takes us through the years of reconstruction from the ruins of war, the golden years of industrialization and social changes, the years of the student movement, the sexual revolution, feminism and the rise of the Communist Party, but also through the years of red terrorism and the slow decaying phase of the 1980s and 1990s, with rampant ex-radical students becoming corrupt power players in the interstices of the state apparatuses and Camorra families controlling the public and private bodies of the country.

“Dissolving Margins”: On the Italian Anthropological Mutation

One of the most recurrent, intriguing and yet obscure concepts to be found in the Neapolitan novels is that of “dissolving margins” [smarginatura]. This is the concept through which Lila describes the experience of her own body – as well as objects and people surrounding her – expanding to break its own boundaries and fall violently to pieces. The first time we encounter this experience is in the first volume, when she is still a young teenager, soon to be married to a wealthier shopkeeper from the rione. It is the 31st of December and everyone is preparing for the New Year’s Eve festivities. Rino (Lila’s brother), Stefano (her future husband), and the other boys who gravitate around Lila and Lenù are particularly excited as they plan to compete with the antagonistic gang of Camorra boys (the Solara family) over who can fire the biggest crackers. Lila watches the spectacle in silence and quasi-disgust:

The thing was happening to her that I mentioned and that she later called dissolving margins. It was – she told me – as if, on the night of a full moon over the sea, the intense black mass of a storm advanced across the sky, swallowing every light, eroding the circumference of the moon’s circle, and disfiguring the shining disk, reducing it to its true nature of rough insensate material. Lila imagined, she saw, she felt – as if it were true – her brother break. Rino, before her eyes, lost the features he had had as long as she could remember, the features of the generous, candid boy, the pleasing features of the reliable young man, the beloved outline of one who, as far back she had memory, had amused, helped, protected her (Vol. 1, p. 176).

Lila’s first encounter with the experience of the dissolving of boundaries occurs when she believes her brother begins to behave like the wealthy and arrogant Camorra boys from the rione. This episode occurs just when Rino, thanks to both Lila’s creative mind as a shoe-designer and Stefano’s promise of investment, finally sees the possibility of making money by beginning an entrepreneurial activity as a shoe-factory owner. In Lila’s eyes, however, the dream of moneymaking has turned her brother into an unreasonable individual in a hurry to get rich. As they both come from very poor families, both Lenù and Lila had always cultivated the dream of becoming wealthy, but now Lila begins to see money differently: “Now it seemed that money, in her mind, had become a cement: it consolidated, reinforced, fixed, this and that.… She no longer spoke of money with any excitement, it was just a means of keeping her brother out of trouble” (179).

Lila will resort to the image of “dissolving margins” on other occasions. But the experience becomes devastating when later in life, after separating from her husband, Stefano, and breaking with her lover, Nino, she ends up working in a meat factory in order to sustain herself and her newborn son. In the factory Lila experiences exploitation, sexual harassment, humiliation, fatigue, and the loss of contact with, and time for, her child’s education. But more than the fatigue of shifts and the impossibility of combining work and care for her son, it is the encounter with politicization in the midst of the student and workers movement of 1968-69 that almost causes her to have a nervous breakdown. One morning, as soon as she arrives at work, she finds out that her account at a political meeting of the many instances of brutality she had witnessed in the factory has been used, without her consent, for a political leaflet by radicalized students in order to target her factory and to urge the workers to revolt. Everyone in the workplace understands Lila is behind the story recounted in that leaflet; her boss threatens to fire her and her co-workers despise her for making their lives more miserable. That night, she is so furious with the students for not informing her of their actions and for getting her into trouble that she feels her body is on the edge of blowing up.

She was getting back in bed when suddenly, for no obvious reason, her heart was in her throat and began pounding so hard that it seemed like someone else’s. She already knew those symptoms, they went along with the thing that later – eleven years later, in 1980 – she called dissolving boundaries. But the signs had never manifested themselves so violently, and this was the first time it had happened when she was alone, without people around who for one reason or another set off that effect (Vol. 3, p. 180).

Dissolving margins is the experience of the known that becomes unknown, of the truthful that becomes false, of the beautiful that becomes ugly, of the familiar that becomes unfamiliar and dangerous. It is the fear of a world that breaks and morphs into monstrous forms. One way to read the notion of dissolving margins is in terms of Lila’s resistance to, and fear of, a world that is changing in front of her eyes. It is Lila’s refusal to accept or to comply with the path to industrialization and phony modernization that Italy is undertaking. In a way, Lila’s horror at the dissolving of margins is her panic in front of what Pier Paolo Pasolini called the “anthropological mutation” occurring in the country in the 1960s.[4] With this term, Pasolini referred to what he saw as the transition from traditional to modern values in Italy. For Pasolini, this was not a positive change, for it meant the homogenization of everyone’s ideas, tastes, desires and appearances brought about by mass consumption. Lila first sees the ugly face of that anthropological mutation when she witnesses how the greed for money transformed her brother from a modest artisan into a greedy individual. But above all, she sees the ugly face of the anthropological mutation and experiences the scattering of her own body when she feels that the political turmoil at her working place is not the result of her colleagues’ own making, but rather of the insincerity and naivety of middle-class students who want to “rescue” the workers:

The students made speeches that seemed to her hypocritical; they had a modest manner that clashed with their pedantic phrases. The refrain, besides, was always the same: We’re here to learn from you, meaning from the workers, but in reality they were showing off ideas that were almost too obvious about capital, about exploitation, about the betrayal of social democracy, about the modalities of the class struggles (Vol. 3, p. 110).

Here again a Pasolinian motif emerges: the “artificiality” and precariousness of the coalition between workers and students. Famously, in 1968 when the police attacked protesting students, Pasolini provocatively took sides with the former. The policemen were the real representatives of the working classes, Pasolini argued, and not the students, whom he labeled petit-bourgeois kids born with a silver spoon in their mouths. Lila looks at the students with that class-inflected Pasolinian eye, and yet she takes sides with them. In spite of her anger at their immaturity, she believes what they say is right. She agrees with their denunciation of capitalism as a source of injustice, even if she is convinced they do not have real first-hand experience of that very injustice. She will thus become a union activist and, through Lenù’s pen, publicly denounces the working conditions in the factory in the pages of the most important leftist newspaper in the country.

When everything is breaking within and around her, when silence and assent would be much easier choices, Lila nonetheless takes sides with the weak and the marginalized. Despite her lack of boundaries, she transmits solidity and embodies an integrity that is the truest mark of her personality. It is to these features of Lila’s personality, to her authenticity and honesty, even in their unpleasant manifestations, that Lenù – who feels fake, inauthentic and “opaque” – is drawn.

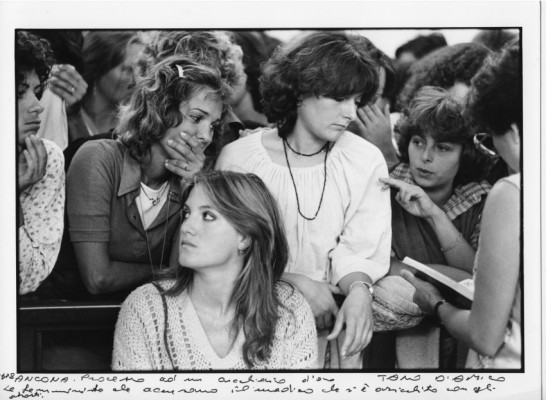

Tano D’Amico

Dissolving the Margins of Class and Gender

The theme of dissolving margins traverses the four books in less explicit and more metaphorical ways when we are confronted with gender and class boundaries. Both Lenù and Lila grew up in working-class patriarchal families where it was not uncommon to see their fathers beating their mothers, or men beating women. These episodes assume quasi-natural and ineffable contours in front of their eyes, belonging to the rubric of customary facts. And yet both girls, from very early on, each in her own way, strive for their independence and emancipation from an environment that oppresses them and that they feel is unfair to women. Lila is the first to recognize and to name the codes of men’s domination over women. She does so in her own non-bookish, but instinctive and radical way: after the disappointment of an intense clandestine love affair with a young intellectual, Nino, she separates from her authoritarian and small-minded husband and decides to live in a partnership with Enzo, a man who does not give her luxury but transmits integrity and political passion, and above all, who respects her. As a factory worker she recognizes especially the sexism and other problems to which working women and mothers are subjected. She describes them in a speech that resembles the powerful and memorable monologue by Gian Maria Volontè in La Classe Operaia va in Paradiso (The Working Class Goes to Heaven):

She said jokingly that she knew nothing about the working class. She said she knew only the workers, men and women, in the factory where she worked, people from whom there was absolutely nothing to learn except wretchedness. Can you imagine, she asked, what it means to spend eight hours a day standing up to your waist in the mortadella cooking water? Can you imagine what it means to have your fingers covered with cuts from slicing the meat off animal bones? Can you imagine what it means to go in and out of refrigerated rooms at twenty degrees below zero, and get ten lire more an hour – ten lire – for cold compensation? If you imagine this, do you think you can learn from people who are forced to live like that? The women have to let their asses be groped by supervisors and colleagues without saying a word. If the owner feels the need, someone has to follow him into the seasoning room; his father used to ask for the same thing, maybe also his grandfather; and there, before he jumps all over you, that same owner makes you a tired little speech on how the odor of salami excites him (Vol. 3, p. 110).

Lila is also the first to understand the power and yet fragility of gender boundaries when she encourages her brother in-law, Alfonso, to feel comfortable in his non-conforming, gay skin.

Lenù, on the other hand, discovers and challenges gender boundaries in a bookish but no less transformative way. Her sister-in-law, Mariarosa, introduces her to feminism and to a consciousness-raising group. Lenù is struck in particular by Carla Lonzi’s famous text “Let’s spit on Hegel.” In this text, Lonzi questioned the possibility of applying Hegel’s master-slave dialectic to the man-woman relationship. For Lonzi, women need to become subjects of a renewed history, thereby putting an end to that condition in which they are merely an hypothesis formulated by others.

How is it possible, I wondered, that a woman knows how to think like that. I worked so hard on books, but I endured them, I never actually used them, I never turned them against themselves. This is thinking. This is thinking against. I – after so much exertion – don’t know how to think. Nor does Mariarosa: she’s read pages and pages, and she rearranges them with flair, putting on a show, That’s it. Lila, on the other hand, knows. It’s her nature, If she had studied, she would know how to think like this. That idea became insistent. Everything I read in that period ultimately drew Lila in, one way or another (Vol. 3, p. 260).

Lenù’s discovery of the transformative potential of feminist thinking and gender-breaking is life-changing; and yet it is beset by deep contradictions. What fascinates her in feminist theories and the consciousness-raising group is not their political implications and activism, but how this feminine model of thought causes in her the same admiration and subalternity she had always felt towards Lila. Lenù does not use this newly found feminist consciousness to become closer to other women, but to get closer to Lila. Unlike the latter – who uses her private experience of gendered inequality and abuse in the factory for public denunciation – Lenù initially exploits the public experience in the feminist group for her personal struggle with Lila and herself. Even later, when she decides to write an essay-style book on the history of Western culture as one in which “men fabricate women,” Lenù tells us about this decision by emphasizing her questionable private motives and ambiguities. She writes about women and flirts with feminists because she wants to impress and seduce a man, Nino. She advocates women’s empowerment and yet lets her lover deceive and disrespect her with his many lies. All passages in the third and fourth volume about Lenù’s relationship with feminism and feminists are traversed by anxiety and the symptoms of the impostor syndrome. As a successful writer, she can make her readers think she has successfully crossed the boundaries of the male-dominated literary canon – her first book was avant-gardist in its explicit sexual content, right on the eve of the sexual revolution – but she can’t trick herself. Lenù’s feelings of insecurity and lack of authenticity concerning her feminist and intellectual credentials, however, cannot be dissociated from her confidence crises related to her class. By crossing the boundaries of gender orders, literary canons and even bourgeois domestic respectability – she leaves her husband and daughters for Nino, a love from her childhood – Lenù gives expression to her anxiety about the uncertain boundaries of her class identity. Education and marriage have allowed her to climb the social ladder and to leave behind the working class environment into which she was born and to embrace a comfortable middle-class milieu. Yet, she always feels a stranger in both classes. While Lila dissolves the margins of her own body and fears the disintegration of the world around her, Lenù dissolves the margins of her gender and class identity. While Lila seemingly faces the earthquake within and around her with sturdiness in the desperate attempt to keep herself and her son unharmed, Lenù lets everything within and around her fall to pieces: her marriage, her relationship with her daughters and her own self.

And yet, Ferrante disorders this binary picture of Lila the authentic and Lenù the inauthentic with the power of her own narrative choices. Isn’t in fact the apparently fake, self-deprecating Lenù also the one who tells us about her struggles for authenticity with impassioned honesty? If the solidity of unfaltering convictions and irreprehensible behavior is denied to her as a woman who lives at the borderline of class and gender hierarchies, what she is left with as a narrator is sincerity: the striving for truth despite the knowledge of its impossible attainment.

The Double and the Uncanny

It has been suggested that Ferrante’s quartet are novels of the couple, of the memorable pair. Like Prince Hal and Falstaff, Settembrini and Naphta, Ferrante’s Lenù and Lila seem to stay impressed in our memory because of the force of their quasi-symbiotic relationship.

To make full sense of these novels, however, particularly of their enigmatic ending, I suggest that we look at Lenù and Lila as two faces of the same person; that we think of Lila as a symbolic projection of Lenù’s fantasy. In this sense, the Neapolitan novels could be also seen as novels of the double and the uncanny, like Poe’s William Wilson, or Wilde’s Dorian Gray. Freud famously linked the theme of the double that was present in German literature of the nineteenth century to the theme of the uncanny.[5] The presence of a pattern of repetition of the same destinies, misdeeds and even names involving two individuals (i.e., the main character and his/her significant Other), is what creates the disquieting feeling of something being unfamiliar, uncanny. In other words, what enables a series of disparate and yet repetitious events in a narration to be experienced as uncanny, according to Freud, is the sensation that they are not coincidental contingencies, but pieces of a puzzle hiding a fateful meaning. More importantly here, for Freud the uncanny emerges from the intimation that the significant other in the novel is not a real person but an automaton, or a shadow of the imagination, onto which the main character mirrors, or projects, his/her own fantasies. From this perspective, it is hard not to see all the ingredients of the uncanny in Ferrante’s quartet.

The lover of Lila the adolescent, Nino, later becomes the lover and then partner of Lenù as an adult. The dream of Lila as a child to become a writer becomes Lenù’s reality later on in life. Both Lenù and Lila give birth to two daughters at roughly the same time and Lila names her daughter after Lenù’s doll, Tina. The two little daughters in turn seem to repeat the paths of their mothers: Lila’s Tina is precocious and extremely intelligent; Lenù’s Imma is instead rather unexceptional. And more importantly, Lila’s daughter disappears into the void, just like Lenù’s doll with the same name had vanished years before and was never found again (until the very end). Yet, this series of momentous coincidences is never merely repetition of the same. All occur at different stages of Lila and Lenù’s life. More precisely, Lenù “realizes” the dreams of her childhood and adolescence – to become Nino’s lover, to be a famous novelist – in her adulthood. And it is at the apex of her success as a writer and of her newfound feminist consciousness that Lenù, this time vicariously, re-lives her childhood’s inferiority complex towards Lila through her daughter’s daily encounter with the more gifted Tina. That is presumably why Tina must go – twice! First as a doll and lastly as Lila’s beloved daughter. Her presence as the reincarnation of Lenù’s unsettling double stands in the way of Lenù’s rebirth as her own self.

Step by step, Ferrante takes us through Lenù’s encounter with, and desire for, Lila as her double. It is a painful and distressing encounter, yet she needs it in order to find herself. Ferrante’s Lenù does not in fact narrate the journey towards the discovery of her own persona as a sort of monadic development of her inner potentiality. Lenù the adult is not an expanded, fully unfolded version of Lenù the child. Rather, Ferrante’s Lenù needs to face and confront Lila, as well as to recognize Lila as her double (whether Lila is fictitious or real is unimportant here) in order to find her own skin. It is perhaps for this reason that only at the end of the fourth novel, in the very last lines, after she mysteriously finds the two missing dolls from her childhood in her apartment building (presumably left by Lila), that Lenù expresses the doubt that she might have lived her own life as the projection, or perhaps even the embodiment of the life of Lila as her Other.

[Lila] had deceived me, she had dragged me wherever she wanted, from the beginning of our friendship. All our lives she had told a story of redemption that was hers, using my living body and my existence (Vol. 4, p. 356).

The bewildering discovery of the two dolls Lenù had always believed to be forever lost sheds light on the darkness of Lila’s disappearance. “Now that Lila has let herself be seen so plainly, I must resign myself to not seeing her anymore,” (357) writes Lenù in a touching final sentence. Now that Lenù can finally see Lila’s original lie, which was pivotal to their life-long friendship, she also understands that Lila cannot come back. Or perhaps, the two dolls are only metaphors for Lenù’s relationship with Lila as her symbolic projection. Revealingly indeed, Lenù tells us that she arranges the dolls “against the spines of her books” while examining them with care and realizing how cheap and ugly they are. Now that she can finally live in her own skin, Lenù is ready to see the two old dolls together as the two conflicting sides of her own personality. She is ready to look at them as relics of that past in which she was a poor girl from the hell of the Italian South. Opposed to that past, she can now affirm her present as a successful writer.

Whatever the meaning the unexpected reappearance of the dolls might have, we are left with a strong feeling of nostalgia and confusion. We understand there are no simple or one-sided truths to be finally disclosed: “real life, when it has passed, inclines toward obscurity, not clarity,” as Ferrante tells us in these last dense lines of the book. Finding oneself through the encounter with the double – and losing the powerful projection of the self that the double represents once her presence is no longer needed – does not mean that one finds any settling truth upon which to rest.

-

For an overview of Fortini’s life and work in English, see Franco Fortini, The Dogs of the Sinai, trans. Alberto Toscano (London: Seagull Books, 2013) and A Test of Powers. Writings on Criticisms and literary Institutions, trans. Alberto Toscano (London: Seagull Books, 2016).

-

Adorno’s line has been translated in English in many different ways. One of the most often quoted ones, however, is: “There is no right life in the wrong one.” See Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections on a Damaged Life, trans. Edmund F. N. Jephcott (London: Verso, 2005).

-

Elena Ferrante is the pseudonym of the author of these novels whose identity is unknown.

-

Pasolini’s notion of anthropological mutation was elaborated in a series of articles appeared between 1974 and 1975 in the newspaper Il Corriere della Sera and in Il Mondo. They are: “Gli italiani non sono più quelli,” Corriere della Sera 10/06/1974; “Il potere senza volto,” Corriere della Sera il 24/06/1974; Ampliamento del “bozzetto” sulla rivoluzione antropologica in Italia, “Il Mondo,” l’11/07/1974; “Il vuoto del potere in Italia, Corriere della Sera, 1/02/1975, “Abiura dalla Trilogia della vita,” Corriere della Sera, 9/11/1975.

-

Sigmund Freud, “The Uncanny,” 1919, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVII (1917-1919): An Infantile Neurosis and Other Works (London: Vintage Classics, 2001), 217-56.