This text is based on Heide Gerstenberger (2017) Markt und Gewalt. Die Funktionsweise des historischen Kapitalismus (Westfälisches Dampfboot) Münster. An English translation will appear published by Brill asMarket and Violence.

Marx’s analysis of the basic structures of capitalism explains why, once established by ‘blood and dirt’, the capital relation can be reproduced in social forms which appear to confirm the absence of brutal force and sometimes even the existence of mutual interest. If labour contracts have existed before the advent of capitalism, it is only with capitalism that the contract has developed into the ideological centre of capitalist forms of production. Any doubt about its relevance was obliterated by the movement for the abolition of slavery. In making contracts into the defining characteristic of non-slavery, abolitionists gifted capitalism with a powerful vindication of its specific forms of exploitation. Its ongoing relevance is present in all the contracts which, starting in the last decades of the 19th century and continuing until today, have been falsified in order to prevent legal action against forced labour.

By insisting on the ongoing presence of brute force in capitalist forms of appropriation, I do not want to minimise the sufferings to be experienced in labour conditions which are considered ‘regular’. Instead, I endeavour to explain that the historical realities of capitalism do not adhere to Marx’s conceptions of history. Brute force was not only the midwife of the new society, then to be reduced to an exception “in the ordinary run of things”. If direct violence against persons is, indeed, no longer a necessity for the reproduction of capitalist social forms of production, it has and is nevertheless constantly made use of. Quite a few Marxists endeavoured to reconcile Marx’s statement about the transition from the phase of so-called primitive accumulation to “the ordinary run of things” in capitalism by declaring that primitive accumulation, i.e. the presence of brutal force, was not restricted to a certain phase of capitalism but is one of its ongoing characteristics. If this is certainly correct as far as historical realities are concerned, there is no way around the fact that Marx thought differently. And this is not the only example where his philosophy of history has intruded into his analysis. Instead, it is constantly present in Marx’s explanations of those developments of capitalism which will produce the preconditions for the better future to which mankind is destined. That these explanations have not been validated by the actual course of history, has to be accepted as critique of any theoretical concept which links structural analysis to concepts of historical teleology. It is this linkage which not only provoked my research into the historical constitution of bourgeois capitalist states but also into the historical functioning of capitalism. The result of the latter can be summed up in a nutshell. It runs as follows:

Exceptions apart, owners of capital make use of all the means to achieve profits which are open to them in a certain place and at a certain time. If direct violence is not one of the practices which are being made use of, this is not prevented by economic rationality but only by public critique and state activity.

I will try to explain some of the findings of this research by relating them to its most vexing theoretical problem: If the resumé allows for exceptions, and rightly so, it nevertheless states that capital owners tend to act in certain ways.

At first sight, this makes my account into an extensive illustration of Marx’s concept of ‘character masks’. But this concept refers to actors in so far as they exist in theoretically explained relations to other actors, be these relations of competition, of opposites, or of the contradiction which is present in any form of capitalist exploitation. It is one of the great achievements of Marx to have explained exploitation as resulting from the systemic characteristics of capitalism and not from the more or less vicious character of individuals.

But as soon as we leave structural analysis and turn to historical realities we are no longer confronted with character masks but with real human beings. And these are not one-dimensional but “pluriel”. The term “l’hommepluriel” was coined by Bernard Lahire in order to explain his reservations about Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus (Lahire: 1998).

While the concept of habitus is not to be mistaken as a modernized version of Marx’s character mask, it is, nevertheless more closely related to the latter than sociologists’ concept of ‘role’. In any case, if the owners of capital have to be considered just as ‘pluriel’ as any other human being, but have, nevertheless, acted most of the time as if they were the character masks of structural analysis, then we have to look for explanations of their behavior which are not sufficiently contained in the structural analysis of capitalism. And, of course, no Marxist worth his or her ilk will have recourse to concepts of the fundamentally egoistic nature of human beings.

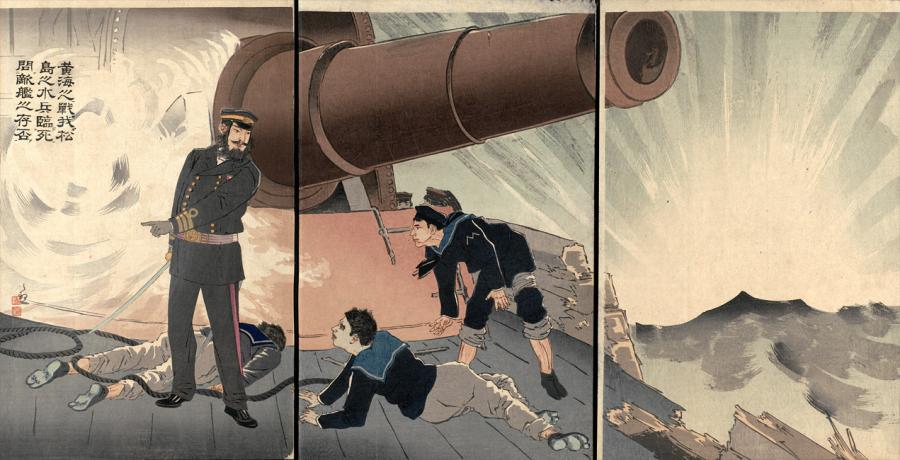

If my exposition of historical developments goes back to the 15th and 16th century, this is not to recant from insisting that capitalism did not start with the world market and has not been brought about by its gains. Instead, I offer an addition to Marx’s analysis of the so-calledprimitive accumulation which may help to explain the historical foundation of long lasting patterns of legitimating violence. When, starting in the 15th century, an European-based world market more or less replaced the Asian based world market of the 13th and 14th century, this amounted to the replacement of a network of more or less peaceful trade with some occurrences of robbing and killing by a system of regular robbery with some occurrences of peaceful trade connections (Chaudhuri:1985:14).

European armed trade was a threat to everyone, including merchants which held trading privileges from competing European princes. If legitimating violence with the task of Christianization was still present in the early phases of the European based world market– much later to be reformulated as an obligation to civilize – we may detect a legacy from the armed trade of pre-capitalism to capitalism which has nothing to do with any merchant capital that may have been accumulated. In granting trading privileges to merchants, European princes also took on the responsibility for all the bloodshed which was being practiced in order to gain the profits which they themselves expected.

This direct responsibility of political powers for the practice of violence in the processes of appropriation has been present in each and every non-European colonial state to have been erected by any capitalist colonising power. The most important contribution to these practices was the legal transformation of subjugated men and women into “natives”, to be legally treated as human beings of minor worth.[1] Colonial states were simply that: institutions for forcing natives to help exploit the natural riches of their home countries.

On the other hand, societies on their way to become examples of metropolitan capitalism came to be governed by an apparatus which revolutionaries declared to be the property of nations. In defining the difference between legality and illegality, these governments thereby also outlined the range of practices citizens could feel justified to make use of. Laws entitle citizens to overlook the possible contradiction of their practices with those concepts of natural law, which had encouraged bourgeois revolutionaries. If, according to dominant interpretation, any such contradiction was obliterated by contracts, this justification, nevertheless, excluded slavery. But the founders of the United States managed to include slavery into the political structures of the Union. By counting slaves as three-fifth of an inhabitant of the slave states in order to increase the number of representatives of these states in Congress, they invented a pattern of bourgeois ethical hypocrisy, which denies any bounds to the dominion of private property. If there were, not only internationally, but also in the United States, more and more men and women who criticized slavery, this does not seem to have affected slavers. Instead, their respective neighbourhoods and later on also the respective state legislations even came to prohibit the practice of gifting a slave with his or her freedom at the death of his or her owner.

I mentioned this development in order to suggest, that in explaining actual behaviour of capital owners, we not only take into consideration economic interests and the existing legal framework, but also the outlooks which are dominant in a historically given neighbourhood. The social force which I tentatively term ‘neighbourhood’ existed and exists in many varieties.[2] If the neighbours of slavers were more or less living nearby, today’s neighbourhoods can also consist of the leading or not so leading employees of a multinational combine. It is in these neighbourhoods that competition has been elevated to the range of an ethical norm. Accordingly, almost anything seems to be accepted amongst these ‘neighbours’ as long as it is practiced for the best of the firm.

But let us go back to slavery. According to Marx and many Marxists, slavery would have had to be abolished sooner or later because it was preventing further development of capitalism.[3] But nowhere has slavery been abolished because it prevented profitable production.

The most convincing argument against the assumption that free wage labour is a structural necessity for the development of capitalism, however, was provided by all those capital owners who, immediately after the abolishment of legal slavery, invented and exploited legal forms of surrogate slavery. Amongst these was the extensive trade in labour contracts which bound Asian coolies to their places of work for a number of years and very often for much longer. Once again, this trade was not abolished because of economic irrationality. Instead, it was ended by the governments of sending countries after reports about the slave-like labour conditions to which coolies were subjugated abroad, could no longer be overlooked. While in the USA and in colonies slave-like labour was predominant in agrarian capitalism, it was also present in industrial capitalism.

Though legal forms of bondage were not as frequent in Europe as elsewhere, they were not absent. Marx knew about the fact, that leaving work without the consent of the capital owner was considered a criminal offence in England[4], thereby limiting contractual freedom even in the most advanced industrialised country. When he refrained from discussing this fact, Marx may have assumed that this criminal law would necessarily be abolished in the course of capitalist development. But when it was, indeed, abolished in 1875, this was not because of any widespread preference for a free labor market, but because the finally achieved extension of suffrage had offered organized laborers the chance to voice political demands during the electoral campaign. That even in the early 1870s many English capitalists profited from the criminalization of the so-called breach of contract, is just one of the countless examples which prove that, exceptions apart, capitalists make use of any possibility to make profits in a certain time and at a certain place.

It was only after World War II that in all of the metropolitan capitalist societies, contractual freedom for labourers was definitely established. Trade unions were accorded the right to deliberate working conditions, thereby reducing the vagaries of individual labor contracts. In terming these developments the ‘domestication of capitalism’ I want to stress that if the ferocity of capitalism maybe temporarily subdued, it will not disappear, but threaten to once again come forward as soon as vigilance is neglected. The labor regime of National Socialism which was instituted after capitalism in Germany had already made inroads into its domestication, is a gruesome reminder of this insight into the political economy of capitalism. On the international scale its relevance was proven correct by recent threats to formerly established labor rights.

Capitalism became globalized when, after the breakdown of the international monetary system, governments of metropolitan capitalist societies abolished restrictions to international movements of capital. This not only furthered the developments of financial markets, it also facilitated investment in production in foreign countries, thereby creating internationalised labour markets in heretofore unknown forms. If this has not completely eradicated the power of labour organizations to demand certain state policies, it certainly reduced their influence. In non-metropolitan capitalist societies as well as in the worldwide shipping business the situation is worse because the existence of a potentially unlimited supply of labourers discourages struggles against violent practices of exploitation.

While my research was mainly focused on violence in the exploitation of labourers, I have also referred to recently expanding practices like the trade in body parts, the dumping of poisonous waste, the grabbing of land, or the trade in military power. There is no question about their disastrous effect on the health and even the life of persons. I, nevertheless suggest that, as with illegality, violence tends to be politically and hence historically defined.

I term ‘violent’ any form of labour exploitation which prevents labourers to leave their place of work, be this bondage the result of some sort of falsified contract, of threats against the respective labourer or his and her relatives, the practice of imprisoning labourers by employing guards, building fences or barring windows and doors, not to forget the practice of refusing shore-leave to seamen for weeks and even months. One has to add conditions which force laborers to work for very long hours and to endure risks to their health without protection. I describe numerous examples but I also point out that since the founding of the International Labor Organization in 1919 one convention after another has defined what practices are internationally deemed to be unacceptable. In condemning certain practices these conventions also define the range of capitalist exploitation which is deemed acceptable. National sovereignty ensures that neither the ratification of conventions by the nationally responsible political bodies nor their actual implementation can be enforced by international commissions. In the 1990s the ILO adjusted its policies to the conditions of globalization. It now endeavors to at least secure the establishment of basic labour rights.

But the chances to attain these rights are reduced when governments advertise offshore conditions of law on the world market for such conditions in order to attract foreign investors. Just like the offshore spheres for financial transactions and for flags of convenience, offshore spheres of production (Special Economic Zones) are legal spheres which are constituted as exceptions from national law. If all of them offer special tax conditions, many conditions are being deliberated between potential investors and respective governments. Until very recently it was common for investors to demand that trade union membership was prohibited for their employees. Recently, such regulations have become less frequent. But the practice has not. Notwithstanding the fact that in increasing offshore spheres, governments trade with national sovereignty, yet they remain officially responsible for conditions in offshore spheres. This means that capital owners are thereby formally exonerated from the stigma of direct political domination.

By offering capital owners the chance to leave the sphere of law in which their economic units are based, they are also presented with the possibility to flee the eyes of a critical local and national public, instead practicing what Marx has called ‘capitalism sans phrase’. Until now the continuation of this form of capitalism is not in danger because the international market in offshore conditions facilitates changes in the geographical location of investments.[5]

Offshore spheres of production are nationally constituted. At the same time they are integrated elements of the globalized political economy of capitalism. If the class relation exists in any form of capitalism, and if it is present in most social struggles of our time, the classes which Marx assumed would organize and teach themselves, thereby getting ready for revolution, are not present in globalized capitalism. There is then no social force which will induce capital owners to overcome short sighted practices of exploitation by creating labor conditions which, according to Marx, embody the historical progress inherent in capitalist social forms of production because they obliterated the brute force of exploitation characteristic of historically earlier forms of production and also because they bring about the preconditions for social revolution. The continuing presence of direct violence in capitalist social forms of production contradicts Marx’s expectations of the history of capitalism. It thereby also contradicts his theory of revolution.

This text is based on: Heide Gerstenberger (2017) Markt und Gewalt. Die Funktionsweise des historischen Kapitalismus (Westfälisches Dampfboot) Münster and on:Karl Marx, Capital: Vol. I

Heide Gerstenberger was Professor for the ‘theory of state and society’ at the University of Bremen in Germany and is now retired. Her research covers a wide range of topics and has been centred on the development of capitalist states. Her work with Ulrich Welke engaged in an empirical analysis of maritime labour. Since 2005, she has been focusing on the history of capitalist societies, and has published in EnglishImpersonal Power: History and Theory of the Bourgeois State(2009, Brill/Haymarket). Her more recent work has been published as Markt und Gewalt(to be translated by Brill soon as Market and Violence). This is an updated version of her HM London 2017 conference paper, initially shared here.

References

Chakrabarty, Dipesh (1989) Rethinking Working Class History, (Princeton Univ. Press) Princeton, New Jersey.

Chaudhuri, Kirti, N. (1985) Trade and Civilization in the Indian Ocean, (Cambridge Univ. Press) Cambridge.

Fragináls, Frank Moya (1985) ‘Plantations in the Caribbean: Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic in the Late 19thCentury’; in: Frank Moya Fráginalset. al, Hg. (1985)Between slavery and free labor: the Spanish speaking Caribbean in the 19th century(John Hopkins University Press) Baltimore, pp. 3-24.

Lahire, Bernard (1998) L’homme pluriel. Les resorts de l’action (Nathan) Paris.

Scott, Rebecca, J. (1985) Slave Emancipation in Cuba (Princeton Univ. Press) Princeton, N.J.

[1] While English governments long upheld, that ‘the rule of law’ was not only valid in Britain but in British colonies as well, this was not only disregarded in real life but even officially changed after rebellions in the 19th century. Because colonial states ruled over potentially constantly rebellious people, it was deemed justified to make the law of war into a constant element of colonial domination.

[2] One of them is the neighbourhood to which Dipesh Chakrabarty pointed when criticizing European concepts of class.

[3] But in Cuba those owners of large plantations which in the second half of the 19th century industrialized sugar production, used slaves until the government of Spain prohibited slavery in 1888. If they hired engineers in foreign countries, they usually made their own slaves into assistants, thereby passing over the free laborers which already worked along with them. (Scott 1985:27;Fraginals1985:3-24)

[4] This is contained in the 24th chapter ofCapital I in the part on “legislation against the expropriated”. “The provisions of the labour statutes as to contracts between master and workman, as to giving notice and the like, which only allow of civil action against the contract breaking master, but on the contrary permit a criminal action against the contract-breaking workman, are to this hour (1873) full in force.”

[5] The globalisation of capitalism has not done away with the influence of neighbourhoods on the actual strategies of profit making, the neighbourhood of our days being the critical international public. From their predecessors it is differentiated by the incessant attempts of more or less organized groups to influence public opinion and thereby induce state action. More often than not this endeavor is counteracted by the dependence of internationally voiced critique on international media and thereby on the conjunctures of the trade in news. If media effectively scandalize certain instances of violent exploitation, official promises tend to be readily forgotten when media coverage moves on, the aftermath of the terrible fires in Bangladesh being an example in case. In order to overcome the potentially disastrous effects of offshore spheres on labor conditions international critique has started to demand that in metropolitan capitalist societies legal responsibility of capital owners be established for labor conditions regardless of their geographical place. While it is to be hoped that this political strategy can reduce violent exploitation for many, its scope is limited.