Hymer died in a car crash in New York State in February 1974. He was 39 at the time. His MIT thesis, completed in 1960, was described as seminal because it was the first piece of writing on international firms (the so-called ‘multinationals’) that offered what the author called a theory of direct investment, arguing that neither international trade theory nor finance could explain the existence of enterprises with foreign operations. MIT refused to have the thesis published and it was only published in 1976 thanks to his supervisor C.P. Kindleberger, who had publicised it in his own book American Business Abroad (1969).

Hymer’s tragically brief life reverses the ‘God That Failed’ trope, in the sense that, starting as an orthodox economist who continued to use neoclassical ideas even into the late sixties, he became increasingly radicalised and came around to a solidly Marxist understanding of the contemporary world. Before saying something briefly about this, here is a very short account of his life.

Hymer was Canadian and has been described as the best Canadian economist of his generation. He was born in Montreal in the early years of the depression, his father a Jewish immigrant from Eastern Europe who ran a clothing store. He graduated from McGill University in 1955, wrote his thesis ‘The International Operations of National Firms’ from MIT in the late fifties, and went on to visit Ghana twice in the early sixties. Here he was active in an informal group called the Marxist Forum, although his own radicalisation would not occur till around 1967. Meanwhile, after joining the economics faculty at Yale in 1964, he and Steve Resnick (1938–2013) began to read Capital together. Like Sartre complaining that there was no chair of Marxism at the Sorbonne when he was a student there in 1925 and that ‘students were very careful not to appeal to Marxism’, describing his own generation in the US Hymer would later write, ‘it was difficult for young people (in America) to gain access to Marx. His language seemed impenetrable, and there were hardly any courses in the universities to help people understand him. In fact, there were few who had any idea even of what was different about Marx’.

Hymer spent the autumn of 1968 at Cambridge with Bob Rowthorn. Here, he joined an informal discussion group that included Rowthorn, Robin Murray, and Geoffrey Kay among others. (When Rowthorn published his 1971 monograph International Big Business 1957-1967, he did so with a title page that said ‘In collaboration with Stephen Hymer’.) Rowthorn, Murray and others would almost certainly have debated whether the internationalization of capital that was driving the postwar boom had left nation-states economically weaker and whether it had not also weakened the ties between capital and its home state. At any rate, thanks in part to the discussions in Cambridge, Hymer is said to have ‘returned to the United States fully committed to the study of Marx’. In 1969, he spent the summer at the University of Chile and it was during this trip that he ‘finally and irrevocably changed his perception of international capital’. If this refers to a further espousal of Marxism it would mean that he felt he had found a language in which to recast much of his thinking about international firms, dealing with them now as an evolution of twentieth-century capitalism. In May 1970, he attended a conference in Hamburg that was also attended by Celso Furtado (the renowned Brazilian economist), Arghiri Emmanuel (the Paris-based Greek economist who had just published the French text of Unequal Exchange) and Giovanni Arrighi among others. It was here that he presented a draft of his paper ‘The Multinational Corporation and the Law of Uneven Development’, which started with a master-quote from Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth.

In the spring of 1970, Hymer taught his first course on Marx, at Yale of all places. Robert Cohen, chief editor of a collection of his writings published some years after he died, tells us that, after being denied promotion and tenure at Yale ‘because of his radicalism’ (that was how Hymer saw it), ‘he was offered a position both at the University of Toronto and at the New School for Social Research in New York City’, decided to remain in the United States, and joined the faculty of the New School as a professor of economics in the fall of 1970. ‘He was now free to teach courses on Marx and to develop his criticisms of economic theory’ (Cohen, ‘On Becoming a Radical Economist’, in Hymer, The Multinational Corporation: A Radical Approach, 1979).

While Hymer discounted any positive correlation between size and growth (the biggest firms did not necessarily grow any faster), firm size was a crucial determinant of direct (i.e. foreign) investment. If the rapid expansion of foreign investment in the fifties and sixties was spearheaded by US firms, this was because they had, through most of their history, exploited economies of scale to achieve ‘giant’ size. But, to Hymer’s mind, size was not enough, corporate form was just as crucial to the huge advantage American firms had built by the 1940s. By this he meant the multidivisional structures that large American firms began to introduce from the 1920s and which were widely adopted after the Second War. Rowthorn tells us that Hymer had ‘great admiration’ for Alfred Chandler. Among radical economists, he was unique in taking both Marx and Chandler seriously (in sentences like ‘the process of capital accumulation has become more and more specialized through time’, Chandler and Marx are inextricably joined). Chandler foregrounded business administration as a key source of American capital’s lead over the rest of the world. Hymer, of course, accepted this but integrated the insight into a framework where the law of increasing firm size was now expressed as ‘a general law of capital accumulation’. In the Hamburg paper, he wrote, ‘The development of business enterprise can therefore be viewed as a process of centralizing and perfecting the process of capital accumulation’. ‘In the modern multidivisional corporation, a powerful general office consciously plans and organizes the growth of corporate capital’. Or, again, ‘Multinational corporations enlarge the domain of centrally planned world production’. But they could only do this thanks to corporate hierarchies that straddled the world, transforming the ‘underdeveloped countries’ into branch-plant countries and reducing their governments to the same ‘middle management outlook’ . Hymer frequently used the image of the skyscraper to convey some sense of how top management alone was the repository of an ‘international perspective’; ‘on a clear day, they can almost see the world’.

A second element that set Hymer apart was his conception of US capital rapidly losing its hegemonic position as competition between large firms of different nationalities started driving the internationalisation of capital from the late sixties. Turning Servan-Schreiber on his head, he argued that ‘in the late 1950s, United States corporations faced a serious “non-American” challenge’ from European and Japanese firms, and foreign investment was their answer to that. ‘It will be easier for the U.S. corporations to counterattack abroad, and to meet inward foreign investment with outward foreign investment’. This image of a dialectic of internationalisation, of successive waves of foreign investment being driven by competition in oligopolistic markets (those dominated by handfuls of the biggest players, e.g. in oil, tyres, pharmaceuticals, etc.) was variously described as ‘cross-penetration’ and ‘cross-investment’, and has of course become a standard feature of the world economy since the 1960s. At Hamburg in 1970, Hymer claimed, ‘The present trend indicates further multinationalization of all giant firms, European as well as American’, and forecast that the rivalry between them (and thus between Europe and America) would ‘probably abate through time’ and turn into ‘collusion’ as those giant firms approached ‘some kind of oligopolistic equilibrium’. And, by the spring of 1972, he was predicting that, where production was no longer the crucial element, international firms would simply outsource it. This passage is worth quoting for its prophetic quality: ‘where product design becomes the dominant element, investment in development and marketing is more important. The large corporations might then prefer to allow small businesses to own the plant and equipment (along with the associated risks) while it concentrates on intangibles’.

In sharp contrast to these positive images was Hymer’s unswerving acceptance of Marx’s critique of capitalism. In his first thoroughly Marxist essay ‘The Internationalization of Capital’, written towards the end of 1971, he defined the corporate hierarchy as rooted in a division of mental and manual labour and noted how those hierarchies were partly designed to break lateral communication at the bottom (among workers). ‘At the bottom of this vertical hierarchy, labor is divided into many nationalities’, which outlines a theme that a colleague and I would go on to discuss fifteen years later in a book called Beyond Multinationalism. However, to my mind, the single most Marxist paper Hymer wrote was one he presented to a conference in Italy in November 1973. This was called ‘International Politics and International Economics: A Radical Approach’ and published in 1975. He argued here that ‘A socialist alternative, under which the working class seizes control of the investment process, could open new possibilities of organizing production and promoting the growth and development of the potential of social labor’. He also suggested that an international capitalist class was emerging whose ‘interests lie (less in any given national economy than) in the world economy as a whole’. In other words, what Hymer was predicting was a deeper integration of national economies as well as alliances between firms of different nationalities.

This was also, in some ways, Hymer’s most optimistic piece of writing, with him forecasting that if ‘during the last twenty-five years, capital has been able to expand and internationalize’, ‘during the next twenty-five years we can expect a counterresponse by labor and other groups to erode the power of capital. This response will take a political form, i.e., a struggle over state power around the central issue of capitalism and its continuance’. What happened, of course, was the opposite; capital struck back with fury, breaking the industrial militancy of the late sixties with massive redundancies and restructuring production worldwide. The fifteen years following Hymer’s death saw major changes. The most dramatic shift was the retreat of American manufacturing capital that became evident, for example, in the near-complete takeover of the US tire industry by foreign competitors in the 1980s (only Goodyear survived). At a more global level, his essential insights proved resilient. Japanese direct investments increased sixfold during the 1980s. Overall, the internationalisation of capital reached staggering proportions, with the outward stock of FDI controlled by companies from the advanced capitalist countries standing at close to $14 trillion by 2008, up from just over $500 billion in 1980. By 2012, international firms coordinated a whole four-fifths of world trade (that is, 80% of world trade occurred within these firms). Of course, the forms in which they did so were more complicated now, since much of that intra-firm trade occurred not just through affiliates but through contractors and independent suppliers, in short, cross-border production networks that began to replace the vertically integrated hierarchies of Chandler’s capitalism with supply chains (replace Fordism with ‘Toyotism’) and that could do so thanks to the ongoing revolutions in maritime transport, satellite communications and ICT more generally.

What is so striking about Stephen Hymer’s work is the nuanced way in which he was able to handle the subject of international capital, viewing the multinational through the lens of the Manifesto as ultimate proof that modern capitalism ‘destroys the possibility of national seclusion and self-sufficiency and creates a universal interdependence’, but increasingly aware of how the promise contained here of a truly internationalized humanity could never be fulfilled under capitalism. With a dreadful disease ravaging large parts of humanity, Big Pharma has made it clear it is opposed to sharing the necessary IP, technologies, data and know-how (what Hymer would have called their ‘technological advantage’) to ensure that ‘as many companies as possible can produce these lifesaving vaccines’. And yet that is the only way of bringing about a rapid expansion of the overall global supply and ensuring equitable access worldwide, as MSF’s Access Campaign has been arguing since December.

By Jairus Banaji

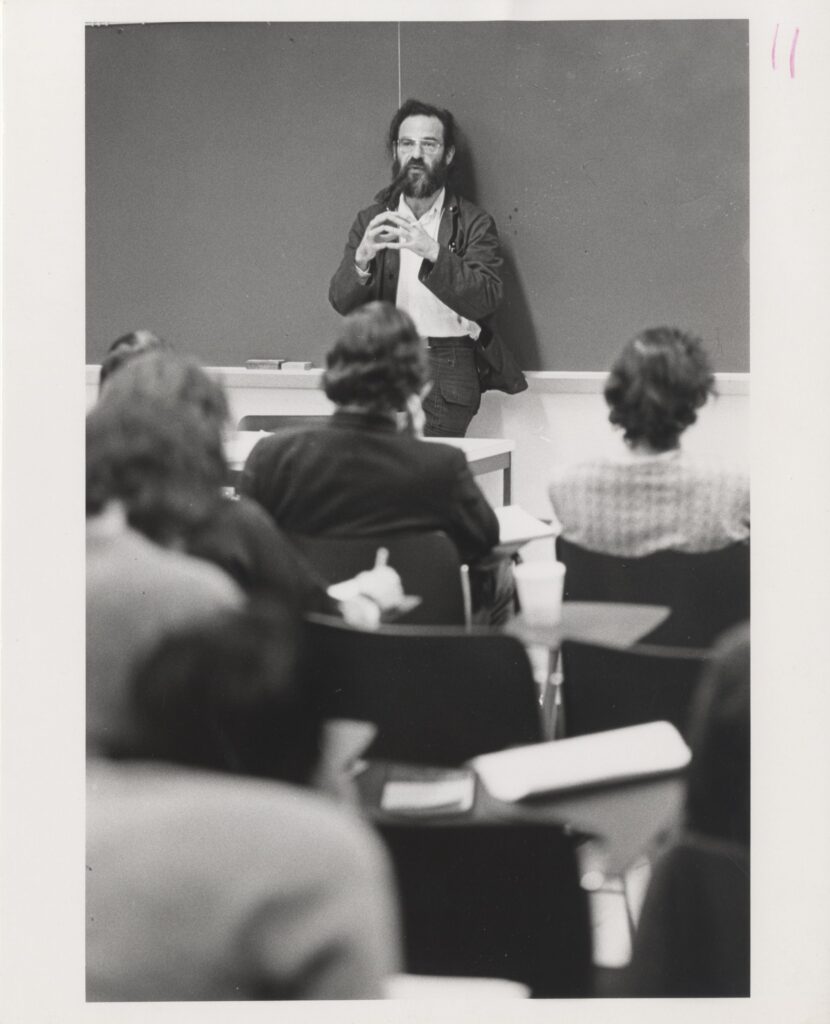

[Photo credit: Stephen Hymer (1934–1974) lecturing at the New School for Social Research c.1971 (photo: Peter Moore).

Photos of Hymer are almost non-existent. The source of this one is the New School Photograph Collection in the New School Archives and Special Collection, New York. (My thanks to Wendy Scheir for locating it.)]