Figures

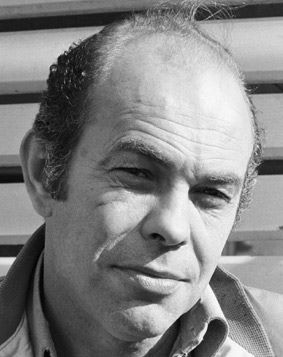

Jacek Kuroń

Jacek Kuroń (left; 1934–2004) and Karol Modzelewski whose arrest, trial and imprisonment in Poland in 1965 contributed to the radicalisation of a whole generation of Polish students in the sixties and to the student strikes of 1968.

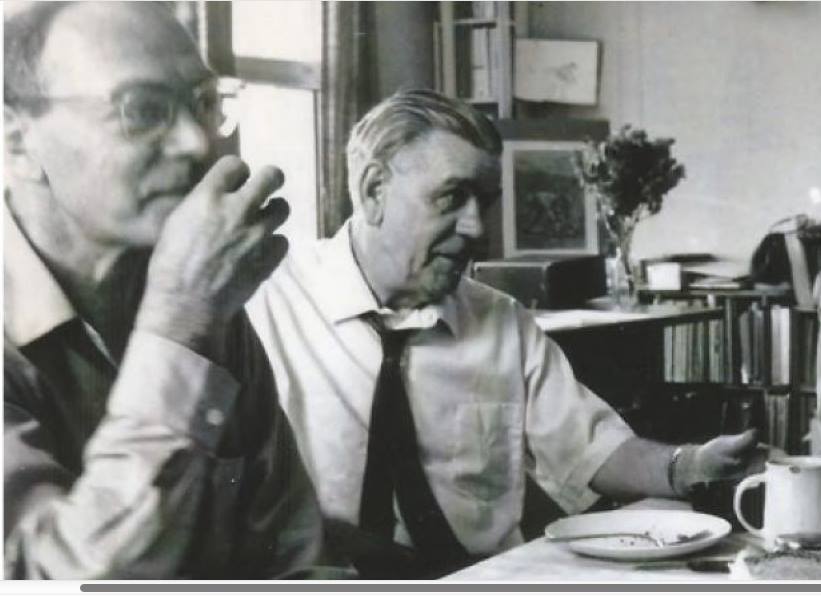

Marc Bloch

Marc Bloch (1886–1944) – with the glasses – who was professor of history at the universities of Strasbourg (1931–1936), the Sorbonne (1936–1939) and Montpellier, and among the most fascinating historians of the twentieth century. He served in both world wars and even wrote a scathing political critique of the French defeat in the Battle of France in 1940, a first-hand account called L’étrange défaite (Strange Defeat) which explains why the government and ruling class were to blame. After the armistice (June 1940), Bloch returned to France, to the unoccupied southern zone where he joined the resistance at Montpellier. He was arrested by the Gestapo in March 1944, tortured and eventually shot on 16 July. This was, as Febvre says, ‘the day after the landings in Provence, when [the Nazis] were ‘emptying’ the prisons by carrying out mass killings of patriots’.

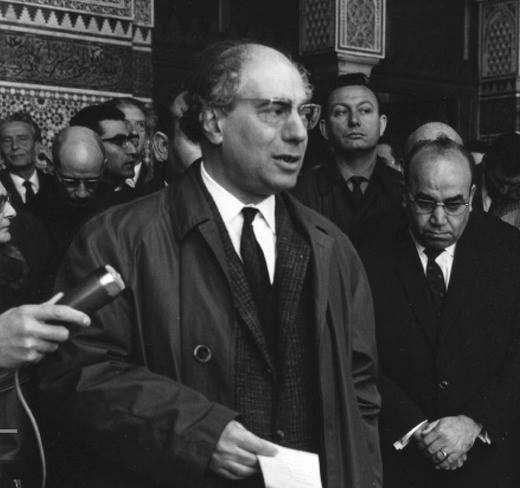

Maxime Rodinson

Maxime Rodinson (1915–2004), the great French Orientalist, Marxist sociologist, author (most famously) of Muhammad (1961) andIslam and Capitalism (1966). Born in Paris to radical Jewish working-class parents, Ashkenazi Jews, who were among the earliest members of the French Communist Party in 1920. They were both murdered in Auschwitz in 1943. Rodinson himself was a member of the party from 1937 to 1958 when he was expelled, having repudiated its evasive stance on Zionism and “exasperated by the restrictions imposed on our thought and research by the intellectual and other cadres of the party”. (In France in the fifties, he says, “it was impossible to publish an article or book, or to make a film, in which the Arabs appeared as at least having some grounds for complaint about Zionist Jews”. The Communist Party refused to rock this boat for fear of losing votes.)

Paul Mattick Sr.

Paul Mattick Sr. (1904–1981), who left Germany for the US when he was 22, shown here with Chomsky’s mentor, the linguist Zellig Harris (to his right).

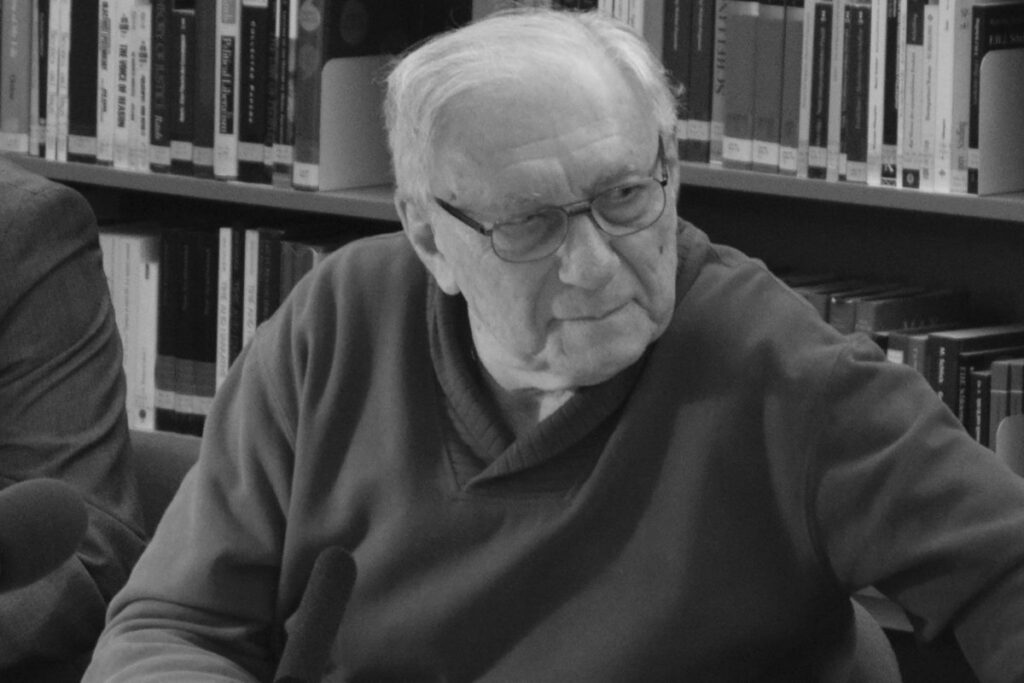

Sadiq Jalal al-Azm

Sadiq Jalal al-Azm (1934–2016), the Syrian Marxist who was professor of Modern European Philosophy at the University of Damascus from 1977 to 1999, and who died in December 2016. Arrested and then jailed for his book Naqd al-fikr al-dini (Critique of Religious Thought) when it was published in 1969, much of his work remains banned in the Arab countries.

Serge Mallet

When the last concentrated burst of class struggle in Europe’s industry receded in the early to mid seventies, two broad visions of industrial politics had come to coexist on the Left. In many ways, these two positions were diametrically opposed political readings of the massive changes that had swept through industry in post-war capitalism in the fifties & sixties. The first was an attempt to restate the case for workers’ control not in terms of abstract theory but by looking at changes in the working class and, behind the class, in the nature of industry as a whole. This was a French innovation and its defining text was Mallet’s 1963 book La nouvelle classe ouvrière (The New Working Class). The other stream was peculiarly Italian and went back to the splits that resulted when Mario Tronti and Antonio Negri broke with Quaderni Rossi (Red Notebooks) and formed their own review Classe Operaia in 1964. The overall perspective of this current, more nebulous than ‘workers control’, is best conveyed by the slogan ‘the strategy of the refusal’.