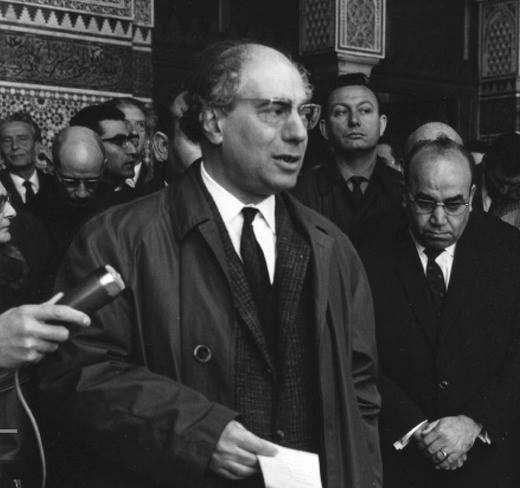

Maxime Rodinson (1915–2004), the great French Orientalist, Marxist sociologist, author (most famously) of Muhammad (1961) andIslam and Capitalism (1966). Born in Paris to radical Jewish working-class parents, Ashkenazi Jews, who were among the earliest members of the French Communist Party in 1920. They were both murdered in Auschwitz in 1943. Rodinson himself was a member of the party from 1937 to 1958 when he was expelled, having repudiated its evasive stance on Zionism and “exasperated by the restrictions imposed on our thought and research by the intellectual and other cadres of the party”. (In France in the fifties, he says, “it was impossible to publish an article or book, or to make a film, in which the Arabs appeared as at least having some grounds for complaint about Zionist Jews”. The Communist Party refused to rock this boat for fear of losing votes.)

Rodinson was frequently subjected to attack from Zionist circles in France which accused him of being a “self-hater” and traitor to the Jews. This thanks to the stand he took, in solidarity with the Palestinians, in regarding Zionism as a form of settler colonialism and the state of Israel as lacking legal foundations.

In his own words, he confessed a “repugnance for Jewish nationalism (common among very many Jews of my generation) even stronger than the repugnance I feel for other nationalisms …this particular nationalism claims me and innumerable other ‘Jews’ who have no desire to adhere to specifically Jewish groupings” (from his Introduction to the brilliant collection of essays published as Cult, Ghetto, and State). Yet, in his interaction with Arab intellectuals in Beirut and Cairo towards the end of the sixties, Rodinson made it a point to confront an insidious anti-Semitism widespread among Arab elites which verged on a kind of Holocaust denial. After the defeat of 1967, he came around to the view that both sides (Palestinians and Israelis) would have to live together in what (in retrospect perhaps naïvely) he thought was the only practical solution to the conflict, viz. a ‘two-state solution’.

In tackling the (essentialist) argument that religious and cultural factors were responsible for the Muslim countries not developing modern capitalism, Rodinson (in Islam and Capitalism) underscored what he saw as the rationalism of the Quran (“the rationalism of the Koran seems rock-like”, p. 90; “the Koran accords a much larger place to reason than do the sacred books of Judaism and Christianity”, p. 91) and turned Weber on his head by suggesting that there was less ideological resistance to profit-seeking in the Islamic world than in the Christian west. Against the maximalism of those Marxists who still think there either is or isn’t a capitalist mode of production in a given society, Rodinson took the much more interesting view that a ‘capitalistic sector’ existed, to one extent or another, in many parts of the world before the full blast of modern capitalism. On a different level, the final pages of this work (which won the Deutscher Prize in 1974) also contained the ominous prophecy that as class struggle intensified in the Muslim world, ‘the ruling strata will make use of Islam to give religious endorsement to their conservative attitudes’ (p. 232).

The Syrian philosopher Sadiq Jalal al-Azm who died in 2016 is a great example of the kind of influence Rodinson exerted on Left intellectual circles in the Arab world.

by Jairus Banaji