I got to know K. Damodaran (1912–1976) some time in 1974, when he was busy setting up the P.C. Joshi Archive in a basement of the old campus of JNU in Delhi. We would pore through the latest available catalogue of New Left Books and decide which titles to order from London. Damodaran was a Marxist of great humility who hardly ever spoke about himself or his past, so I had no real idea then how pivotal he had been to building the Communist movement in Kerala. Uniquely for someone who had been so important in the (united) Communist Party of India, by the late 1960s, Damodaran had become profoundly critical of Stalinism and the legacies it encumbered the party in India with.

Here are some interesting excerpts from the fascinating interview which Tariq Ali conducted with him in 1975 (which was then published in New Left Review, Sept.-Oct. 1975):

We were told that Stalin was the ‘great teacher’, the ‘guiding star’ who was building socialism in the USSR and the leader of world socialism. And being both new to communism and relatively unschooled in Marxism and Leninism I accepted what I was told. There is a tradition in Indian politics of political gurus enlightening the masses and this tradition suited Stalinism completely. Hence we could accept anything and everything that we were told by the party elders who themselves were dependent for their information exclusively on Moscow. This was the atmosphere in which I was brought up as a communist. However, there were some comrades who were extremely perturbed at the information on the massacres which was coming out of Moscow. Philip Spratt, one of the communists sent to help build the CPI from Britain, became so demoralized and disillusioned with Stalinism that he abandoned communism altogether and became a liberal humanist and towards the end of his life an anti-communist. He was an excellent comrade who played an invaluable role in helping us at an early stage. The Congress left wing was also extremely critical of the purges taking place in Moscow and some of their leaders were extremely disgusted by the propaganda contained in the CPI front journal National Front, which depicted Trotsky as a poisonous cobra and an agent of Fascism. Even Nehru, who was one of the first Congressmen who popularized the Russian Revolution and Soviet achievements, expressed his disapproval of the purges in 1938. But for us, communists, in those days Trotskyism and fascism were the same. I must confess to you that I also believed that Bukharin, Zinoviev, Radek and other victims of Stalinist purges were enemies of socialism, wreckers and spies working in the interest of imperialism and fascism…Looking back on that period I feel that all this was a big tragedy not just for us, but for the whole communist movement. Can you imagine: Trotsky had vehemently opposed Fascism and had warned the German communists against the trap they were falling into and this same Trotsky was labelled by us and thousands of others as a fascist […]

[G]iven the twists and turns of the CPI, the ultra-leftism of the 1948 [Party] Congress proved to be disastrous. The masses were not prepared to overthrow the Nehru government. On the contrary large sections of them identified with it, and the CPI slogan: ‘This Independence is a Fake Independence’ merely succeeded in isolating the party. The armed struggle which was launched together with this slogan led to the deaths of many cadres and imprisonment and torture of others throughout the sub-continent. The analysis of the Nehru government as a comprador stooge government of imperialism was another mistake, as it implied that there was no difference between the colonial British administration and the postcolonial Nehru government. As is now commonly accepted by Marxists, the Indian ruling class was never a comprador class in the real sense of the word. It enjoyed a relative autonomy even during the colonial occupation. To argue that it was a comprador class after Independence was not only ultra-left in the sense that it underpinned a wrong strategic line, it also demonstrated the theoretical inadequacy of Indian communism. Many of the themes of that period were taken up again in the late sixties by the Maoist rebels in Naxalbari and other parts of India and we know with what disastrous consequences. Apart from the fact that hundreds of young people were killed, thousands tortured and the movement went from setback to setback, we still have its legacy in the shape of thousands of political prisoners imprisoned by the Indian ruling class. The tragedy here being that the prisoners are virtually bereft of any mass support […]

[F]our years after the transfer of power, Stalin and other leaders of the Soviet Union considered India as a colonial country under British imperialism. Not surprisingly the Party Conference (Calcutta, Oct. 1951) approved the new line, especially because it had the blessings of the ‘greatest Marxist-Leninist and the leader of world revolution’. This was the thinking of the majority of our comrades at least until 1956. I, too, subscribed to this absurd view for some time, but soon doubts arose and I began to argue that India was politically free.”

Here is Damodaran’s insight into what he thinks drove the CPI/CPM split in 1964:

Many people have written that the CPI/CPM split was a pure reflection of the Sino-Soviet dispute. This is not correct… In my view the major reason for the split was internal differences related to the question of electoral alliances. Ever since the fall of the Kerala ministry a discussion of sorts had been taking place and it reached a head in 1964. If you study the party documents from 1960 to 1964 you can trace the real causes of the split. There is a consistent theme running through all these documents: parliamentary cretinism. On this there are no major differences between the two sides. There is agreement on the need to win more elections in the states and more seats in the Lok Sabha. That is the road to communism in India. There is a supplementary slogan embodied in the formula: ‘Break the Congress monopoly’. It is around this that differences develop. Some party leaders state that the key is to break the Congress monopoly, even if this means having the Jan Sangh or the Muslim League as a partner. Others state that the best way to break the monopoly is by aligning with the progressive sections of the Congress against its right wing. Thus the debate which led to a split in Indian communism was not on differences around how best to overthrow the existing state and its structures, but on how to win more seats. In my view it was tactical differences which led to a split.

Finally, when Tariq asked him what his views were on Trotsky:

I am not a Trotskyist. Stalin was my idol. That idol is broken to pieces. I don’t want to replace a broken idol with a new idol even if it is not a broken one, because I don’t now believe in idolatry. I think Trotsky, Bukharin, Rosa Luxemburg, Gramsci, Lukács and other Marxists should seriously be studied and critically evaluated by all communists. Marxism will be poorer if we eliminate them from the history of the world Communist movement… I think some of the important contributions by Trotsky like his essay on bureaucratization published in Inprecor in 1923, In Defence of Marxism, On Literature and Art, History of the Russian Revolution and other works are valuable and some of his ideas are still relevant. This does not mean that I agree with everything Trotsky said or wrote. The development of Marxism needs a critical eye.

By Jairus Banaji

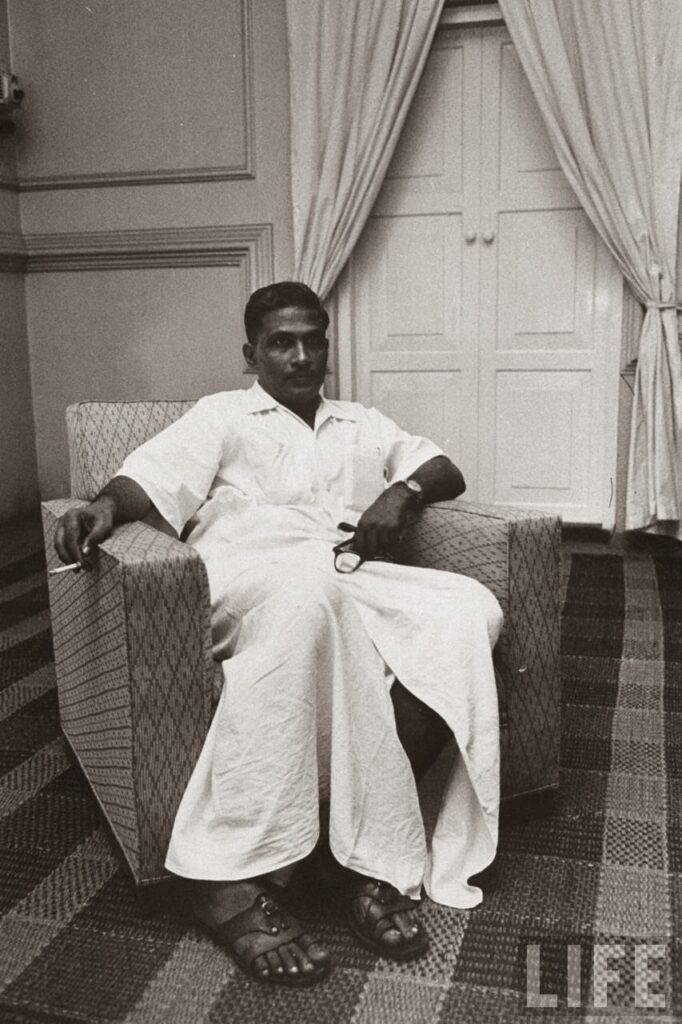

[Photo credit: K. Damodaran in 1958 (Photo: James Burke).]