Allen Ruff

Abstract

The appearance in English of the three volumes of Karl Marx’s Capital, published by the Chicago-based socialist publisher, Charles H. Kerr & Company between 1906 and 1909, marked a significant event in the global dissemination of socialist thought. That project would not have taken place without the conscious internationalist commitment of Kerr & Co.’s activists to provide the key works of Marxism to the US working class movement. As such, the publication of Kerr’sCapital, a standard throughout the English-speaking world until the mid-1960s, cannot be fully appreciated without some understanding of those who carried it out and how the undertaking came about.

***

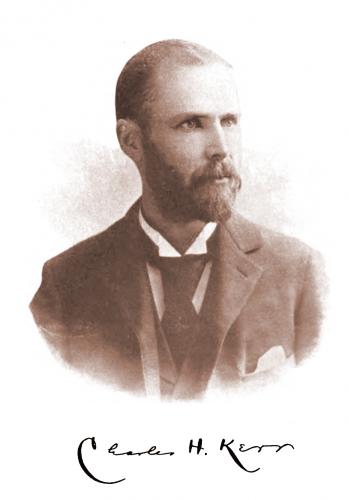

Born in 1860, Charles Hope Kerr apprenticed in Chicago’s publishing trade in the early 1880s after graduating from the then State University of Wisconsin. He started the firm bearing his name in 1886 and gradually turned his energies toward the publication of radical titles as his social and political consciousness evolved due in large part to the Windy City’s harsh social and political realities and glaring contradictions.1 Attracted during the depression ridden 1890s to the populist reform movement with its utopian hope of building of a ‘Cooperative Commonwealth’, Kerr published an increasing array of books and pamphlet tracts on monetary reform, railroad regulation and government control of the banking industry, as well as the monthly New Occasions, ‘a magazine of social and industrial progress’.

During the latter part of that decade, the company published an expanding list of titles by utopian socialists, radical feminists, anarchists, single-taxers, bimetallists, Fabians, freethinkers, evolutionists as well as a number of utopian panacea novels. In 1897, Kerr launched The New Time: A magazine of social progress which he later described as a ‘semi-populist, semi-socialist magazine’. Along contributions from a who’s who of turn-of-the-century American reform, its pages carried occasional communications from socialist labour champion Eugene Debs, as well as a regular ‘Scientific Socialismcolumn of news and views on the progress of Social Democracy in the US and abroad.2

Kerr’s connection with the Socialist International had roots in 1899. The Chicago branch of the Socialist Labor Party (SLP), one of the earliest organisational expressions of Marxian socialism in the US, launched the weeklyWorker’s Call that March and Kerr soon cultivated fraternal relations with the paper’s editor, Algie M. Simons.3

Like Kerr, an alumnus of the University of Wisconsin, Simons initially became acquainted with Marxist thought while a research assistant to the progressive professor of political economy, Richard T. Ely. Upon graduating in 1895, he took a job with the University of Chicago settlement house on the city’s South Side, where he researched working class living conditions in the stockyards districts for the Municipal Board of Charities. Simons’ experiences and observations in the ‘Back of the Yards’ left him morally outraged and disillusioned with gradual liberal reform efforts and he moved leftward. He joined the SLP in 1897 and became editor of the Worker’s Call.4

Simons’s vigorous commitment to ‘scientific socialism’ had immense impact on Charles and his wife, May Walden Kerr. She later recalled that the two of them had ‘sopped up a lot crazy ideas that we had to give up to make way for Marxism’ and how the articulate, analytical strength of Simons’s arguments among the small circle of activists who regularly gathered at the Kerrs’ home engendered an enthusiasm ‘that nearly set the house afire’.5

As her husband later put it, ‘like numerous other Americans, we were looking for real socialism, but as yet knew little about it’;Kerr, Charles H. ‘Our Co-operative Publishing Business: How Socialist Literature Is Circulated is Being Circulated by Socialists,’ International Socialist Review (HenceforwardISR) 1, 9: pp. 669–72.6 that he had not been ‘inside the movement’ before 1899 ‘due to the accident of its not being presented to me’ but that he ‘had not the slightest difficulty in accepting the logic of the socialist position when once perceived’.7

While there already was a long history of socialist activity, largely but far from exclusively of a utopian variety in the US, the Marxist-based socialist movement in the United States at 1900 lagged far behind its European counterparts. Simons and Kerr attributed such ‘backwardness’, in part, to a lack of awareness and resources. Kerr later recounted that ‘when we began our work the literature of modern scientific socialism was practically unknown to American readers …’ and that what was available was largely ‘… of a sentimental, semi-populistic, character … of doubtful value to the building up of a coherent socialist movement’. As Simons put it, ‘…American socialist literature has been a byword and a laughing stock among the socialists of other nations’.8

Determined to remedy the situation, the duo embarked on a number of collaborative publishing projects as Kerr announced in June 1899 that ‘the course convinced us that half-way measures are useless, … our future publications will be in the line of scientific socialism’.‘Socialist Books’, Worker’s Call, June 24, 1899.9Simons became vice president of the company in January 1900 and editor of the company’s monthly, the International Socialist Review (ISR), a ‘magazine of scientific socialism’, launched the following July.10

Under Simon’s editorship until 1908, the monthly aired socialist perspectives on a broad range of political and social questions. With articles by a veritable ‘who’s who’ of the national and international movement, it became the most important socialist theoretical publication in the country. Regular features included monthly column reports on the ‘World of Labor’ by the socialist trade unionist Max Hayes, and ‘Socialism Abroad’, a digest of movement developments in Europe and elsewhere edited by Ernest Untermann, the German-born emigré and future translator of the Kerr editions of Capital.

The ISR functioned as the primary promotional vehicle for the venture as Kerr utilised its pages to offer deep discounts on its titles to those subscribing to the monthly, investors in the company, and to Socialist Party locals or individual ‘socialist sales agents’ purchasing bundled quantities. A baseline source of company support, alongside minimal sales revenue and an occasional personal loan, came primarily from hundreds, then thousands of shareholder investors whose only ‘dividends’ remained generous discounts on the firm’s list of books and pamphlets.

Kerr began offering a lengthy list of 32-page duodecimo five cent pamphlets, ‘The Pocket Library of Socialism’ starting in March, 1899 with Woman and the Social Problem by Simons’ wife, the socialist feminist May Wood Simons.11 Wrapped in red glassine and priced as low priced $6 per 1,000 copies to company shareholders, the series contained thirty-five titles by 1902 and sixty plus by 1908 including Marx’s Wage-Labour and Capital, translated by the English socialist J.L. Joynes and issued as number seven of the series in1899 and Marx on Cheapness, number fifty, appearing in 1907. The Library by that time had reached a circulation in the hundreds of thousands.12

The company employed a number of different strategies to expand its lists of socialist titles. Kerr, for instance, purchased imprints, plates and copyrights of works previously published in the US. The firm, for example, obtained rights to titles previously issued by the International Library Publishing Company, the SLP’s New York-based operation, among them A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (Kerr edition,1904). In 1907, Kerr purchased the copyrights to additional titles including Marx’s Civil War in France and The Eighteenth Brumaire and Paul Lafargue’s The Right to Be Lazy from the Debs Publishing Company, which had acquired them in 1901 from the International Library.13

In 1899, the Simons’s young son died accidentally. To help them recuperate from their loss, a circle of the couple’s Chicago associates contributed funds to send the them to Europe toward the end of the year. Given the opportunity and with letters of introduction in hand, they met with a number of European socialist notables. In France, they met with Jules Guesde and Paul Lafargue. In England, they spent time with Keir Hardie and H.M. Hyndman and became acquainted with the leader of the Belgian movement, Emile Vandervelde. In possession of numerous publications and a list of newfound correspondents as well as ideas for a number of publishing projects, the couple returned to Chicago late May 1900.14

An extended list of adaptations and translations began to appear in the company’s catalogue soon afterward as Kerr translated French and Italian titles and the Simonses worked from the German. May Wood had already translated Karl Kautsky’s Frederick Engels His Life, His Work and His Writings (1899) and Algie Simons assisted in the translation of Wilhelm Liebknecht’s No Compromise-No Political Trading. Kerr meanwhile translated Vandervelde’s Collectivism and Industrial Development as well as the first of several works by Paul Lafargue, who gave the company permission to publish his Socialism and the Intellectuals (1900) shortly after meeting the Simonses. The couple also translated Kautsky’s The Social Revolution (The Erfurt Program). The company would also issue works from the Italian, most significant among them Kerr’s translation of Antonio Labriola’s Essays on the Materialist Conception of History.15 Kerr had established trade connections prior to the turn of the century with the London firm of Swan, Sonnenschein, the publisher in 1887 of the authorised English edition of Capital, Volume I. The company in 1900 issued an edition of Frederich Engels’s Socialism, Utopian and Scientific, translated from a French edition by Edward Aveling and published by Sonnenschein in 1892, and Kerr proudly advertised it as the company’s ‘first cloth bound socialist book’. The Kerr lists soon included additional standard Marxist works such as the Communist Manifesto, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, and Engels’ Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, the latter translated by Ernest Untermann.16

By 1905, the company’s catalogue also included a number of works by some of the key figures of Britain’s broader socialist movement. Kerr had already issued serialisations of William Morris’s News from Nowhere, published by Sonnenschein in 1893, and Robert Blatchford’s Merrie England in The New Time. He issued both works in updated book form and also published Blatchford’s Imprudent Marriages and Morris’s Useful Work versus Useless Toil as part of the Pocket Library series. Kerr subsequently published Blatchford’s other works, Britain for the British (1902) and God and My Neighbor (1904). The Pocket Library also included Hyndman’s Socialism and Slavery, a critique of Herbert Spencer. The company issued Edward Carpenter’s Love’s Coming of Age (1903), and in cooperation with Sonnenschein, imported his Towards Democracy (1905). The Kerr list also came to include Socialism, Its Growth and Outcome by E. Belfort Bax and William Morris (Sonnenschein,1893/ Kerr, 1909).17

Capital comes to America: the forerunners

The 1867 edition of Das Kapital bore the names of the Marx’s Hamburg publisher, Otto Meisner as well as ‘New York: L.W. Schmidt, 24 Barclay Street’ on its title page and the work quickly became available to the small circles of German socialists in the US. Excerpts of it were published in the Arbeiter Union, edited by the German ‘Forty-Eighter’ Adolph Douai between October, 1868 and June 1869. A first English extract, a broadsheet published by the ‘First International, New York Section’ appeared in 1872.18

Beginning in April 1876, the English language weekly organ of the then-named Social Democratic Working-Men’s Party, The Socialist (New York), began running a series of chapter by chapter summaries of Capital accompanied by quotes from Marx. The installments, thirteen in total, continued after The Socialist became the Labor Standard with the formation of the Workingmen’s Party of the United States and ran through August 19, 1876. The apparent editor and translator of the series was Douai, a contributing editor of the Labor Standard who at the time had begun work on a full translation of Kapital.19

Marx, in October, 1877, had prepared revisions with the intent of having it translated and published in the US and had actually sent them to Sorge at Hoboken, New Jersey. Writing to Sorge earlier, Marx passed along instructions for Douai to compare the 2nd German edition with the more recent, revised French edition and he promised to send the updated French volume for Douai. But the project fell through, according to Engels, ‘for want of a fit and proper translator’.20

An early English-language abridgment of Capital translated by Otto Weydemeyer, son of the German revolutionary Joseph Weydemeyer, was published at Hoboken by Sorge, c. 1875, as a 20cm, forty-two page pamphlet,‘‘Extracts from the Capital of Karl Marx’. Weydemeyer’s source was a summary of Capital by Johann Most published at Chemnitz in 1873, a text which Marx and Engels found unsatisfactory and disappointing.21 Those ‘extracts’ were later serialised in the Labor Standard beginning on 30 December 1877 as well as in the Chicago Socialist, and the New Haven Workmen’s Advocate.22

Writing under the pseudonym of John Broadhouse, H.M. Hyndman carried out an English translation from the extant German edition of Das Kapital’s first ten chapters, published in October, 1885. Engels, writing to Sorge in April, 1886 described the work as ‘nothing but a farce’ and ‘full of mistakes to the point of ridiculousness’.23

Regardless, in late 1885, the publisher, union job printer and home of the ‘Labor News & Publishing Association’, Julius Bordollo & Company at 705 Broadway, New York began offering installments of the Broadhouse-Hyndman work, apparently re-set in-house, of a ‘first English translation … in 27 parts at 10 cents; subscription price for the whole work, $2.50.’ The source for the Bordollo reprint evidently was To-Day – a monthly magazine of scientific socialism imported from London and distributed by Bordollo.24 The monthly, initially edited by J.L. Joynes and E. Belfort Bax and purchased by Hyndman in 1885, carried forty installments of the Broadhouse-Hyndman work between October, 1885 and May, 1889, publicised as the‘First English translation of Karl Marx’s Capital’.25

Then, in early January, 1887 what was then ‘Swan, Sonnenschein, Lowrey & Co., London’ issued 500 copies of the first authorised English edition of Capital, a critical analysis of capitalist production. Translated from the third German edition by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling under Engelsssupervision, the work initially appeared as a two volume octavo set. Its first run sold out within two months and an additional five hundred appeared that April, as half the total number went to the US.

Shipped as publisher’s sheets printed at Perth by S. Cowan & Co. and the Strathmore Printing Works and bound upon arrival, two separate shipments made their way to New York. One appeared with a tipped-in imprint bearing the name ‘New York, Scribner & Welfored’.26 A presently unknown quantity went to Bordollo who issued the two octavo volumes bound in green cloth with ‘J. Bordollo, New York’ gilt stamped on the feet.27 Bordollo inserted a separate title page announcing…

THE GREATEST WORK OF THE AGE ON POLITICAL ECONOMY. CAPITAL, A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF CAPITALIST PRODUCTION, BY KARL MARX. Only authorized translation by the life-long friends of the author, SAMUEL MOORE, assisted by EDWARD AVELING, AND EDITED BY FREDERICK ENGELS. In 2 vols., Demy 8vo. Cloth, $700(Sic). Sent post-paid, $7.20. JULIUS BORDOLLO […], 104-106 East Fourth Street, NEW YORK.” [Emphases in original.]28

Contemporary back matter advertisements in the company’s pamphlets proceeded to list the firm as the work’s ‘American Agent’.29

Swan, Sonnenschein & Company went on to publish single-bound editions of Volume I in 1889 and 1891, printed at Aberdeen University Press by John Thompson & J.F. Thomson.30 They were distributed in the US through a formal arrangement with Appleton & Company at New York, with the latter’s name appearing on the title page above Sonnenschein’s. Of the 1,500 copies issued in London between 1887 and 1891, 794 were sold in Britain; and 700 made their way to the US.31. (Sonnenschein would subsequently issue The First Nine Chapters of Capital, a separate volume “reprinted from the stereotype pages of the complete (sic) work,” in 1897.)

Using the Sonnenschein Lowrey two volume 1887 edition and the joint Appleton & Co. 1889 imprint, the Humboldt Publishing Company at New York completely reset and released its own edition.32 That version initially appeared between 1 September 1890 and 15 October 1890, serialised as numbers 135 thru 138‘double number’ issues of the ‘Humboldt Library of Science’. Binding the four installments together, the company then proceeded to issue its single volume the following year, which Engels criticised as an unauthorised ‘pirate’ upon receiving word of it from Sorge. Bound in red cloth and stamped on the front cover with the Humboldt trademark, the volume was promoted as a book showing ‘how to accumulate capital’ and reportedly sold some 5,000 copies.33

The Kerr project

The Kerr publication was truly an internationalist effort. The company, in cooperation with the Worker’s Call, had initially imported a number of the Sonnenschein single volume edition in October 1901 and in May, 1902 sent a cash order to London for two hundred and fifty additional copies. Informing the ISR’s readers that the ‘inferior American edition’ was no longer available, Kerr offered generous advance sale discounts on the volume’s regular price of $2.50 since ‘the co-operative house of Charles H. Kerr & Company was not organized to make profits, but to serve the interests of Socialism…’.34

In December 1902, Kerr informed his readers that a third shipment of the work, ‘complete so far as it has yet been translated into English’, had come from London; that the first shipment, arriving the preceding June, had sold out ‘in a very few short weeks’, and that the company had placed a second order that arrived the month before, but which quickly went to filling back orders.35

At that time, Volumes Two and Three did not exist in English and Kerr, as early as November 1902, expressed the desire to translate and publish a complete three volume edition. He wrote that such a project would cost over $2,000 and expressed the hope that the necessary funds could be raised through the sale of company stock. He promised that the work would begin as soon as enough stock subscriptions were pledged.36

When that funding did not materialise, he set out to find other support for the project as well as a competent translator, one not only fluent in German and English but also well versed in Marxist economic theory. The company, through Simons, asked H.M. Hyndman in London for assistance, but when that did not happen, Kerr then turned to Ernest Untermann.37

Born in Brandenburg, Prussia in November 1864, Untermann had studied paleontology and geology at Humboldt University in Berlin and upon graduating, was ‘drafted into the great army of the unemployed’ before becoming a merchant seaman. He first arrived in United States in1881 and spent most of the next decade travelling the world aboard various merchant vessels. Following a short radicalising stint in the German military and a brief return to Humboldt, during which time he became a socialist, he made his way back to New York where he became a US citizen in1893.

A member of the SLP in the late 1890s, he contributed regular columns to an assortment of socialist periodicals, including the Worker’s Call under Algie Simons’s editorship and its successor, the Chicago Socialist. Joining the Socialist Party of America at its 1901 inception, he was a signatory of the 1905 founding manifesto of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), went on to serve on the Party’s National Executive Committee in 1908-10 and ran as the SP candidate for Governor of Idaho in 1910 and the US Senate from California in 1912.38

Already associated with the Kerr Company, he had previously written various pieces for the ISR, translated European articles for its pages, and compiled a monthly international update on ‘Socialism Abroad’. He also did the translations from the German and Italian for a number of Kerr titles, including, as mentioned, Engels’s Origin of the Family (1902) and, from the Italian, Enrico Ferri’s The Positive School of Criminology (1906) and Antonio Labriola’s Socialism and Philosophy (1907).

In April 1900, Kerr announced the first title of the ‘Library of Science for the Workers’, a series of primarily German works on natural science and evolution, issued with the intent ‘to silently undermine the theological prejudice against socialist principles’, several of which Untermann translated. The series also included his own Science and Revolution (1905) and Kerr soon published his original work of political economy, The World’s Revolutions (1906).39

Untermann’s previous translations had been done without compensation, but with a wife and daughters, he required some sort of support if the monumental task of revising volume one and translating volumes two and three was to proceed. To assist in the undertaking Kerr finally secured the financial assistance of Eugene Dietzgen, by way of Wiesbaden, Germany, and Zurich, Switzerland.40

Eugene’s father, Joseph Dietzgen, a leather tanner by trade, was an autodidact well-versed in materialist philosophy and political economy, and a First Internationalist comrade of Marx and Engels. He first migrated to the US after 1848 and moved back and forth across the Atlantic on several occasions. During a third US sojourn in the 1880s, he became active in New York’s German emigré socialist circles and in 1885 became the editor of Der Sozialist, the ‘central organ’ of the German language section of the Socialist Labor Party. Following the Haymarket bombing of May 1886, he moved to Chicago and took up the editorship of the Chicagoer Arbeiterzeitung after its anarchist editor August Spies, eventually one of those hanged as an alleged conspirator in the bombing, was arrested.41 Two of his own works, both translated by Untermann with financial backing from Eugene, The Positive Outcome of Philosophy (with an introduction by Dutch socialist Anton Pannekoek) and Philosophical Essays, were issued by Kerr in 1906.

Upon his father’s urging, Eugene Dietzgen moved to the US in 1881 after completing his formal education in the classics, philosophy and the natural sciences at Berlin. Settling in Chicago, he went on to head an industrial firm bearing his name that specialised in the production of drafting and engineering tools, and did quite well. He also was active in socialist circles in Chicago and nationally and was selected to represent the Social Democratic Party of America (a forerunner of the Socialist Party) at the International Socialist Congress in Paris, 1900.42

Sometime after the turn of the century, he contracted tuberculosis and retired from the business world and returned to Germany and then Switzerland. From there with the surplus extracted at Chicago, he became the patron of various publishing ventures of the Second International, including Karl Kautsky’s Die Neue Zeit, the foremost theoretical journal of German Social Democracy. Kerr had known Dietzgen before he left Chicago and Algie Simons reestablished connections with him on successive trips to Europe and through a correspondence with Kautsky. Untermann was an admirer of the elder Dietzgen and also apparently had some earlier connection to Eugene, who agreed to subsidise Untermann’s translation of Marx’s opus.43

Untermann set to work on the massive project during the first half of 1905 while living on a chicken farm in Orlando, Florida. He later recalled that,

I couldn’t have done it on what Kerr paid me…, but Eugene Dietzgen paid me a total of $5.00 per page, so I built up a little chicken ranch that panned out well enough to keep my family and myself in groceries. I did the translating after I got through fighting skunks, opossums, snakes, and hawks and for a while it was doubtful whether the chicken business belonged to me or to preying animals. But I won out after a while….44

As he proceeded, he also found time to do an eight-part series of articles on ‘The second, third and fourth volumes of Marx’s Capital’ for the Chicago Socialist that appeared between February and April 1905.45 Those installments became the bases for his Marxian Economics: A Popular Introduction to the Three Volumes of Marx’s Capital, released as volume thirteen of the company’s ‘International Library of Science’ series in 1907.

Untermann not only translated Volumes Two and Three, but also revised and edited a new edition of Volume One. In his ‘Editor’s note to the first American edition’, penned at Orlando and dated July 1906, he explained the reasons for redoing the work.

As he recounted it, more or less, the first English translation of Capital, Volume I, had appeared in January 1887. Overseen by Engels, its translators, Moore and Aveling utilised the third German edition that had integrated changes made by Marx for the second edition (1872) along with the first French edition appearing that same year. In 1890, Engels, using notes left by Marx, edited the proofs for a fourth German edition and comparisons with the French version. But Swan Sonnenschein did not adopt the changes in its subsequent English issues.

Untermann’s Volume One utilised that revised fourth German edition. Comparing the Swan Sonnenschein version page by page in the process, he found some ten pages of additional text not present in the earlier English rendering and integrated those. He also revised the volume’s footnotes.46

Selling for $2.00 and $1.20 to shareholders by Kerr, the first 2,000 copies of Volume One, ‘… revised and amplified by Ernest Untermann …’ appeared in December, 1906, with new, added features — an appendix of ‘Works and Authors Quoted in Capital’ and a topical index done by Untermann.47 Promoting the three volumes later on, Kerr would note the index of some 1,400 topics as ‘the best economic dictionary available in any language.’48

That first run sold within the year and the company issued an additional 2,000 copies in late 1907.49 Kerr could inform his ISR readers that the company had sold a total of some 8,000 copies by November 1909. With Volumes Two and Three available by that latter date, he began offering the complete set, ‘by express, prepaid, as a premium to anyone sending six dollars for the Review six years to one address, or for six copies one year to six NEW names…’.50

Translated from the second German edition, Volume Two, ‘The process of circulation of capital’, appeared in July 1907. Sonnenschein had placed an advanced order for 500 copies for it and a London edition, bound in red cloth and embossed on the front cover and spine with ‘Half Guinea, International Library’ and ‘Sonnenschein’, and ‘Charles H. Kerr & Company, Chicago’ and ‘Swan, Sonnenschein, London’ on the title page soon appeared.

Translated from the 1st German edition, Volume Three, ‘The process of capitalist production as a whole’ was originally scheduled for printing in early 1908. While noting that the translation was paid for by Dietzgen ‘as a gift to the American socialist movement’ and that the Second International patron had pledged additional monthly sums to secure articles from European socialists and to help out with the company’s deficit, Kerr wrote that an additional $2,000 was needed to cover production costs. He requested that his readers order the volume in advance to help defray that expense.51

Volume Three finally appeared in July 1909 and Kerr began offering the volumes singly and as a complete three volume set. All three volumes bore the union ‘bug’ of John F. Higgins, the company’s long-time printer and as such became the first ‘authorized’ edition produced in a union shop. The Kerr edition immediately became the accepted English version, as Swan, Sonnenschein, in conjunction with Kerr, began to distribute it throughout the English-speaking world.

The Kerr edition of Capital passed through a number of separately dated print runs through the 1910s and imprints appeared as late as 1933. In 1936, the company sold its original plates of Volume One to the Modern Library and the New York house issued its own hardback imprint, with ‘Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1906’ remaining on the copyright page (a source of future confusion for bibliographers and antiquarian booksellers, alike).52

That volume’s dust jacket noted that, ‘With one-sixth of the habitable world actually governed by Marxian doctrines and with the rest of the world increasingly agitated over the possible spread of communistic social orders, an acquaintance with the fundamental principles of Karl Marx becomes more and more essential to every person who is genuinely interested in world history today and in the forces behind the ever sharpening clash between fascism and the Left…’ Successive Modern Library editions appeared in 1945 and after.

While other English editions of Capital appeared, such as the translation done by Cedar and Eden Paul published in London by Allen & Unwin in 1928, Kerr’s three volume edition in one form or another remained the standard English text until the appearance of the Progress Publishers edition in 1967, superseded in 1976 by the Penguin edition translated by Ben Fowkes.

As for the Kerr Company, it experienced various ups and downs including an onslaught of government repression including the suppression of the International Socialist Review, vital to its functioning, during World War I. The company survived that period’s ‘Red Scare’ and continued on well after its namesake retired in 1928 after passing its reins on to a next generation of socialist activists associated with the Proletarian Party, an early communist grouping that arose out of the splintering of the Socialist Party in 1919.53 Holding on through the bottom of the 1950s McCarthy era, the venture was saved from passing out of existence in 1971 by yet another generation of socialists, anarchists and labour activists committed to its project. It experienced somewhat of a revival in the 1980s, passed its hundredth anniversary in 1986, and continues its existence as the oldest socialist publishing house in the world.

On his regularly appearing “Publisher’s Notes” page of the ISR, Kerr would often emphasise that the company was organised to do just one thing — to bring out books valuable to the international socialist movement and to circulate them at prices affordable for working class readers.54 Certainly, the publication of the full English edition of Capital remained the crowning achievement of that project.

References

Primary:

Bax, E. Belfort and J.L. Joynes, To-Day: the monthly magazine of scientific socialism. London: 1884–1889. ‘Index of articles’. Available at: <http://www.marxistsfr.org/history/international/social-democracy/today/index.htm>

Charles H. Kerr & Company Archives, Chicago: Newberry Library.

Curry, Lily 1886, Anti-syllabus New York: Julius Bordollo and Company. (Available at:<http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/digital/collections/cul/texts/ldpd_6516724_000/pages/ldpd_6516724_000_00000014.html?toggle=image&menu=maximize&top=&left=>

Ernest Untermann Papers, Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society.

Morris Hillquit Papers, Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society, Box 1, Folder 5: Charles H. Kerr to Morris Hillquit, Oct. 4,1905.

International Socialist Review, Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1900–1918.

Kerr, Charles H. [1903], Cooperation in Publishing Socialist Literature, Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co.

Kerr, Charles H.1904, A Socialist Publishing House, Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company.

Kerr, Charles H. 1924, Radical Books on Economics, History, Social Science, Psychology and Evolution, Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company.

Marx, Karl 1875, Extracts from the Capital of Karl Marx, Hoboken, N.J.: F.A. Sorge. [https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/005751722]

Marx, Karl 1887, Capital. A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production, Volume I (trans. from 3rd German edn. by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling. Swan Sonnenschein, Lowrey & Co., London.) Two volumes. 8vo. xxxii, 364; (ii), 365-816 pp.

Marx, Karl 1889, Capital; a Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production. Translated from the third German edition, by Samuel Moor and Edward Averring. Edited by Frederick Engels, New York: Appleton & Company, London: Swann Sonnenscehin. <https://www.raptisrarebooks.com/product/capital-a-critical-analysis-of-capitalist-production-karl-marx-first-edition-rare/>

Marx, Karl [1891], Capital: Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production,New York: Humboldt Publishing Co. Large 8vo. xviii, 506, (52).

Marx, Karl 1906, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume One. The Process of Capitalist Production. Translated from the third German edition, by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling and edited by Frederick Engels. Revised and amplified according to the Fourth German edition by Ernest Untermann. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company.

Marx, Karl 1907, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume Two: The Process of Circulation of Capital. Ed. Frederick Engels. Trans. from the 2nd German edition by Ernest Untermann. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company.

Marx, Karl 1909, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. III. The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole. Frederick Engels, ed. Ernest Untermann, trans.. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company; Library of Economics and Liberty [Online] http://www.econlib.org/library/YPDBooks/Marx/mrxCpC.html.

May Walden Kerr Papers. Chicago: Newberry Library.

Morris Hillquit Papers. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society.

Most, Johann, Kapital und Arbeit: Ein Populärer Auszug aus “Das Kapital” von Karl Marx [Capital and Labour: A Popular Excerpt from “Capital” by Karl Marx]. Chemnitz: G. Rübner, n.d. [1873]. Revised 2nd edition, 1876.

‘Pocket Library of Socialism’ (1899–1910), Charles H. Kerr & Co., Chicago. http://www.beasleybooks.com/home/plscatalog.pdf.

Untermann, Ernest 1907, Marxian Economics — A popular introduction to the Three Volumes of Marx’s ‘Capital’, Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company.

Secondary:

Adams, Frederick B., Jr., 1939, Radical literature in America: an address… to which is appended a catalogue of an exhibition held at the Grolier club in New York City, Stamford, CT: Overbrook Press.

Buhle, Mari Jo 1981, Women and American Socialism 1870–1920, Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Buhle, Paul 2013, Marxism in the United States: A History of the American Left, 3rd. Edition. (London: Verso).

Buhle, Mari Jo; Paul Buhle & Dan Georgakis, eds. 1998, Encyclopedia of the American Left, 2nd Edition, London: Oxford.

Carter, John & Percy H. Muir, eds.. 1967, Printing and the Mind of Man: A Descriptive Catalogue Illustrating the Impact of Print on the Evolution of Western Civilization During Five Centuries, New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Cochran, David. ‘A Socialist Publishing House,’ History Workshop, 24 Autumn, 1987, pp.162–165.

Commons, John R., et.al., History of Labor in the United States, Volume II New York: MacMillan, 1935.

Easton, Lloyd D.1958, ‘Empiricism and Ethics in Dietzgen’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 19, pp. 77–90.

Foner, Philip S. 1967, ‘Marx’s ‘Capital’ in the United States’, Science & Society, 31, 4, pp. 461–466.

Foner, Philip S. 1947, History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 1: From the Colonial Times to the Founding of the American Federation of Labor, New York: International.

Hillquit, Morris 1910, History of Socialism in the United States, New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

Karl Marx Memorial Library, Luxembourg 2017, ‘Karl Marx, Capital, first American editions’ [typescript]. Available at <http://karlmarx.lu/CapitalUS1.htm>

Kipnis, Ira. 1972, The American Socialist Movement 1897–1912, New York: Monthly Review.

Kreuter, Kent and Gretchen Krueter 1969, An American Dissenter: The Life of Algie Martin Simons, 1870–1950, Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

Pittenger, Mark 1993, American Socialists and Evolutionary Thought, 1870–1920, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Martinek, Jason D. 2010, ‘Business at the Margins of Capitalism: Charles H. Kerr and Company and the Progressive Era Socialist Movement’, Business and Economic History On-Line 8: <http://www.thebhc.org/sites/default/files/martinek.pdf>

Martinek, Jason D. 2012, Socialism and Print Culture in America 1897–1920, London: Pickering & Chatto.

Ruff, Allen 1993, ‘A Path Not Taken: The Proletarian Party and the Early History of Communism in the United States’, in Ron C. Kent, et.al., eds., Culture, Gender, Race, and U.S. Labor History, Santa Barbara:Praeger, 43–57.

Ruff, Allen 2011,‘We Called Each Other Comrade’ – Charles H. Kerr & Company, Radical Publishers Oakland: PM Press, [Chicago: Univ. of Illinois Press, 1996].

Uroyeva, A. [Anna Vasilʹevna] 1969, For All Time and All Men, Moscow: Progress.

Image: Portrait published in The Free Thought Magazine [Chicago], vol. 14, no. 1 (Jan. 1896), pg. 1.; Digital editing by Tim Davenport (“Carrite”) for Wikipedia, no copyright claimed for the work, file released to the public domain without restriction.

- 1. Ruff 2011, pp.1–55.

- 2. Ruff 2011, pp. 56–81.

- 3. Kerr 1903; Kerr 1904.

- 4. Kreuter & Kreuter, pp. 42–5.

- 5. May Walden Kerr Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago. Box I, Folder 2, and ‘diary for 1944’, box 10.

- 6. Kerr, Charles H. ‘Our Co-operative Publishing Business: How Socialist Literature Is Circulated is Being Circulated by Socialists,’ International Socialist Review (Henceforward ISR) 1, 9: pp. 669–72.

- 7. Kerr 1904.

- 8. [Algie Simons] ‘Salutatory’, ISR 1, 1: p. 54.

- 9. ‘Socialist Books’, Worker’s Call, June 24, 1899.

- 10. [Algie Simons] ‘Salutatory’, ISR 1, 1: p. 54.

- 11. On May Wood Simons: Mari Jo Buhle, pp.166–8; Ruff 2011, p. 235, n.13.

- 12. Ruff 2011, p.85.

- 13. Contract between International Publishing Company and the Debs Publishing Company’, 31 May 1901; Box 3, Folder 43, Charles H. Kerr & Company Archives, Newberry Library, Chicago. Cited in Martinek 2012, p.167, n. 53.

- 14. Kreuter & Kreuter, pp. 46–54.

- 15. Ruff 2011, pp. 87–8.

- 16. Ruff 2011, p. 88.

- 17. ISR 2, 6: p. 479; Ruff, p. 86.

- 18. Foner 1967.

- 19. Foner 1967.

- 20. Marx, 1889: Engels, ‘Preface to the English edition’; Marx to Friedrich Sorge, September 27, 1877 and October 19, 1877, Marx-Engels Collected Works: 45: pp. 276-7, 282-3. On Douai, see: Commons, History of Labor I, 224, n. 39.

- 21. Kapital und Arbeit: Ein Populärer Auszug aus “Das Kapital” von Karl Marx (Capital and Labour: A Popular Excerpt from “Capital” by Karl Marx). Chemnitz: G. Rübner, n.d. [1873]. Revised 2nd edition, 1876.

- 22. Marx 1875; Uroyeva, p. 235; Foner, p. 464.

- 23. ‘Engels to Sorge’, Science and Society 2, 3.

- 24. Curry, 1886: Backmatter.

- 25. Bax, E. Belfort and J.L. Joynes, 1884-1889.

- 26. Foner 1967, p. 466.

- 27. Description available at: <https://www.vialibri.net/552display_i/year_1887_0_1104215.html>

- 28. ‘Karl Marx, Capital, first American editions’ [typescript], Luxembourg: Karl Marx Memorial Library, 2017. https://karlmarx.lu/CapitalUS1.htm

- 29. Foner 1967, p. 466.

- 30. See: inside front flyleaf, available at: <https://archive.org/details/capitalcriticala00marx/page/n7/mode/2up>

- 31. Uroyeva, pp. 227–8; Marx1889.

- 32. Marx 1891; Uroyeva, p. 235.

- 33. Uroyeva, p. 235–6.

- 34. ISR, 2, 11, Dec. 1902: p. 830. That ‘inferior edition’ was most likely the Humboldt version or conceivably the English edition of Gabriel Deville’s The People’s Marx — a popular epitome of Marx’s capital, translated by the future Kerr company associate Robert Rives LaMonte and issued by the SLP’s International Library Publishing Co at New York in 1900. For the Deville work, see: https://www.marxists.org/archive/deville/1883/peoples-marx/index.htm.

- 35. ISR 3, 6 Dec. 1902: pp. 379–83.

- 36. ISR 3, 5 Nov. 1902: pp. 317–18.

- 37. H.M. Hyndman to Simons, April 3, 1902, Box I, Folder 3, Algie M. Simons Papers, Wisconsin State Historical Society, Madison.

- 38. Untermann, Ernest. ‘How I Became a Socialist’, The Comrade, 2, 3, Dec. 1903. For a sampling of Untermann’s writings, see: ‘Anarchism and Socialism’, The Comrade 3, Oct. 1903: p.18; ‘The Decline of Capitalist Democracy’, Chicago Socialist, Jan. 1901: p. 4; ‘The Tactics of the German Socialist Movement’, Chicago Socialist, 26, 1903; ‘Mind and Socialism’ ISR 1 April 1901: p. 4; ‘Labriola on the Marxian Conception of History’, ISR 4 March 1904: pp. 548–52; and ‘An Endless Task’, ISR 7, Nov. 1906: p. 285. Ruff 2011, p. 89.

- 39. Ruff 2011, 86; 263, n. 27.

- 40. [Kerr, Charles H.] ‘Why We Need Your Stock’ ISR 3, 5 Nov. 1902, pp. 317–18; ‘Publisher’s Department’ ISR 7, 6 Dec. 1906, pp. 380–1.

- 41. Dietzgen, Eugene. ‘Joseph Dietzgen; A Sketch of His Life’, in Eugene Dietzgen, ed., Ernest Untermann. trans., Philosophical Essays of Joseph Dietzgen Chicago: Kerr, 1906; Ruff 2011, p. 238.

- 42. Kipnis, p. 88.

- 43. Ibid; May Walden, various recollections, Box I, folder 2, and diary for 1944, box 10, May Walden Kerr Papers; Charles H. Kerr to Morris Hillquit, Oct. 4, 1905, Box 1, folder 5, Morris Hillquit Papers.

- 44. Ernest Untermann to Marius Hansome, Feb. 28, 1938, Reel 1: ‘Correspondence,’ Ernest Untermann Papers, Madison: Historical Society of Wisconsin.

- 45. ‘The Second, Third and Fourth Volumes of Marx’s Capital’, Chicago Socialist, Feb. 22; March 4, II, 18, 25; April 1, 8, I5, 1905.

- 46. Marx, 1906.

- 47. [Charles H. Kerr] ‘Publisher’s Department’ ISR 7, 6 Dec, 1906: pp. 380–1.

- 48. Kerr, 1924.

- 49. ISR, 8, 7 Dec. 1907: p. 383.

- 50. ISR, 10, 5 Nov. 1909: p. 470.

- 51. ‘Marx’s Capital’, ISR 7, 3, Sept. 1907: pp. 188–9; 8, 11 May 1908: pp. 717–8. Re: Volume Three see: <http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/marx-capital-a-critique-of-political-economy-volume-iii-the-process-of-capitalist-production-as-a-whole>

- 52. See, for example, Marx, Capital : a critique of political economy …. New York : Modern Library, 1906: Haithi Trust Digital Library listing, available at: <https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100334065> or, the OCLC World Cat listing: Marx, et.al, Capital : a critique of political economy … New York : The Modern Library, [1906]:<http://www.worldcat.org/title/capital-a-critique-of-political-economy/oclc/783523>

- 53. Ruff 2011, pp.198–9. On the Proletarian Party, see: Ruff 1993.

- 54. [Kerr], ‘Publisher’s Department’ ISR 6, 12, June 1906: p. 705; 7, 5 Dec. 1906: p. 380; 7, 10 April 1907, p. 637.