identity

Feminism Against Crime Control

ISSUE 26(2): IDENTITY POLITICS

At the height of the Black Lives Matter movement, I had a typical interaction with a liberal. He claimed to support the protesters, at least in principle. However, he thought the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson was ‘a poor choice of case’ to rally around (if only they had consulted him!). It would fail to impress ‘the public’, he claimed, because the police officer in that incident was ‘probably justified’. As evidence, he cited the media smear accusing Michael Brown of shoplifting shortly before he was gunned down. I refused to concede the shooting would have been justified even if this smear were true. Given the structural racism of the existing order of property, I argued, surely it would be a strategic dead-end to endorse police powers to attack anyone who transgressed it.[1] ‘Oh, I see’, he said, ‘so you are against the police’. Immediately he parried: ‘But suppose a man were raping a woman…’

The point of this anecdote is not simply to illustrate the ease with which the liberal mind slips from thoughts of property to thoughts of women’s bodies, but to highlight an assumption I take to be widespread, including among feminists: the struggle against sexual violence is fundamentally at odds with any deep opposition to the criminalizing state. By ‘the criminalizing state’ I mean the police, criminal courts, prisons, detention centres, surveillance apparatus, border guards, the military, and so on. Taking sexual violence seriously, it is generally assumed, means inducing the state to overcome its notorious unwillingness to ‘punish perpetrators’ and ‘protect vulnerable women’.[2] Of course, this must involve criticising existing institutions insofar as they fail – and fail systematically – to do so. However, for the struggle against sexual violence thus conceived, distrust of these institutions must be mitigated. The aim, to put it crudely, cannot be toundermine the state’s power to criminalize, but towield that power against the perpetrators of sexual violence. Bernstein calls this the project of ‘feminism-as-crime-control’.[3] Within the framework of options defined by this assumption, caring about sexual violence means side-lining concerns about state violence and the classed and racialized construction of ‘criminality’. Conversely, political strategies seeking to disrupt and challenge existing processes of criminalization appear to demand that we downplay the problem of sexual violence. It seems we must be either rape apologists or state apologists.

This assumption is at work in both sides of the debate around ‘Governance Feminism’, or so I will argue. Governance Feminism is defined by its most prominent critic, Janet Halley, as the ‘incremental but by now quite noticeable installation of feminists and feminist ideas in actual legal-institutional power’.[4] Emphasising the punitive aspects of governance, Elizabeth Bernstein labels this ‘a carceral turn in feminist advocacy movements’.[5]From collaboration with border regimes in the drive to criminalize ‘sex trafficking’, to the ‘pink-washing’ of neoliberal gentrification (concern for the safety of women and queers being transfigured into calls for ‘the removal of race and class Others from public space’, to the delight of property developers), feminism-as-crime-control is everywhere in evidence[6] – and, significantly for our purposes, is understood by its critics as a pernicious form of identity politics. As Wendy Brown argued over twenty years ago, this brand of feminism mobilises asocial identity defined by injury and vulnerability – the sexually violated woman – to demand coercive state action, then washes its hands of the oppressive consequences through a show of powerlessness.[7]

Governance Feminism’s most important theorist-advocate, according to both Brown and Halley, is Catharine MacKinnon. The increasingly go-to position for those critical of ‘the carceral turn’ is therefore to reject MacKinnon’s ‘radical feminist’ analysis of sexual violence (the content of which we will come to shortly).[8] Meanwhile, however, aspects of this analysis are gaining traction in philosophy departments via work on ‘hate speech’, objectification, and silencing.[9] In this context, MacKinnon’s work constitutes an important challenge to dominant liberal understandings of concepts like freedom, speech, and consent. However – and here MacKinnon’s assumed affinity with Governance Feminism again rears its head – this project of MacKinnon-mainstreaming still tends to presuppose that liberal states must ultimately be the political agents, and ‘hate speech’ legislation the political means, to put a radical feminist analysis into practice.[10] If there is a feminist revolution going on in political philosophy, critics of carceral politics are not invited.

My aim is to shake up the entrenched battle lines of these debates. One thing MacKinnon and her anti-statist critics seem to agree on, and that I want to challenge, is the close connection between: (a) endorsing a radical feminist analysis of sexual violence – what Halley dubs the ‘subordination paradigm’; and (b) endorsing the project of feminism-as-crime-control.[11] Now, I do not wish to deny that there is any such connection; my intervention is more orthogonal. I want to ask: what reasons might the radical feminist analysis of sexual violence itself give us to be suspicious of strategies that embrace the punitive state? In raising this question, I hope to show those sympathetic to MacKinnon’s analysis that they have reasonsfrom their own point of view to consider a more state-sceptical politics. Equally, though, I hope to persuade those in ‘the other camp’ not to dismiss MacKinnon’s analysis of sexual violence wholesale simply because of its association with Governance Feminism; some of its insights, I suggest, might be mobilised in another direction.

In Part I (‘Subordination’), I outline those aspects of MacKinnon’s analysis I take to be most pertinent. I will show, firstly, how she takes this analysis to justify state-power-wielding strategies, and secondly, how her critics take it to be implicated in such strategies, and therefore reject it. In Part II (‘Insubordination’), I go on to propose three ways in which the radical feminist analysis of sexual violence might support a politics more alert to the violence of criminalization, hence more antagonistic towards the punitive state.

To be clear, these are not arguments for a politics of purity, for ‘keeping our hands clean’ by never relying upon, utilizing, or engaging with the state, as if that were even possible. The state is obviously not a monolith; it is multifaceted, porous, often contradictory. Sometimes one of its branches can be fought with the aid of another of its branches, to some effect. Fighting to expand access to Legal Aid (a function of the state) can be part of fighting against women’s incarceration (another function of the state) or deportation (another function of the state), to take just one example. In fact, rejecting the quest for purity is at the heart of what I am trying to do. MacKinnon is a flawed theorist. Governance Feminism as a form of identity politics causes real harm, in which she is complicit. And yet, while the charge of state apologism levelled against MacKinnon is well-founded, securing a conviction against her, then swiftly arranging the mass deportation of her tainted ideas from our political communities, will not take us much further towards emancipation. On the contrary, I think reducing everything she has ever said and done to grim identity with her worst moments would itself exhibit the carceral logic that insists the world must be simply divisible into good and evil, allies and apologists. This logic imposes unity, sameness, unchangeability on whatever it finds. It delights in the application of labels, ungraciously lopping off aspects of reality that do not fit the preconceived scheme. Contradictions cannot be recognised. The possibility of transformation cannot be thought. Another flawed theorist called this ‘identity thinking’.[12] We might call equally call it (one kind of) identity politics. Looking for secret passageways between the hostile encampments of MacKinnon’s supporters, on the one hand, and her critics, on the other, is my attempt to get beyond denunciations and put a critique of these politics into practice.

MacKinnon argues that sexual violence is the norm rather than the exception under conditions of male domination. Indeed, she argues that the very categories ‘male’ and ‘female’ are constructed through the material practices of eroticised hierarchy jointly known as ‘sexuality’:[13]

Sexuality [...] is a form of power. Gender, as socially constructed, embodies it, not the reverse. Women and men are divided by gender, made into the sexes as we know them, by the social requirement of its dominant form, heterosexuality, which institutionalizes male sexual dominance and female sexual submission. If this is true, sexuality is the linchpin of gender inequality.[14]

Women’s vulnerability to sexual violence is the result, not of some apolitical given called ‘biology’, but of a pervasive system of social power.[15] Sexual violence – the normalised use of women as objects – in turn props up that system. Rape, sexual harassment, intimate partner violence, forced reproduction,[16] ‘prostitution’,[17] and pornography consequently take centre stage in MacKinnon’s analysis of ‘male power as an ordered yet deranged whole’.[18] Sexual violence is the lens through which she views gender politics.

At the heart of MacKinnon’s account is a critique of the liberal concept of consent as it is encoded in laws which purport to prohibit rape but, in her view, merely ‘regulate’ it:

Consent is supposed to be women’s form of control over intercourse, different from but equal to the custom of male initiative. Man proposes, woman disposes. Even [in] the ideal it is not mutual. Apart from the disparate consequences of refusal, this model does not envision a situation the woman controls being placed in, or choices she frames. Yet the consequences are attributed to her as if the sexes began at arm’s length, on equal terrain, as in the contract fiction.[19]

The problem with ‘consent’, MacKinnon argues, is that it is blind to the social power relations that actually make people do things, or go along with things, or not quite managed to say no to things in a way that gets taken seriously. It does not distinguish between enthusiastic mutuality and reluctant submission in the absence of any acceptable alternative. It ignores the ways women are socialized into passivity, silenced by dominant representations,[20] and ‘kept poor, hence socially dependent on men, available for sexual or reproductive use’.[21] ‘Consent’ is routinely imputed to women simply because the thing happened and they did not stop it, never mind how they felt about it or how unequal the conditions. While taking for granted the formula ‘man fucks woman; subject verb object’,[22] the liberal notion of ‘consent’ simultaneously maintains the fantasy that we are pure choosing agents, abstracted from all material conditions and power inequalities, hence free by default. Against this, MacKinnon insists that freedom of the kind feminism should aim at is incompatible with subordination – with being an object at another’s disposal, bargaining from a position of weakness; insofar as women are subjected to these conditions, there is an important sense in which we are not free.

1.2. If the state is male how come you love it so much?

MacKinnon takes this analysis of sexual violence to ground a feminist politics that aspires to wield state power against the perpetrators: the rapists, the pornographers, the sexual harassers, the pimps, the ‘traffickers’, and so on. Yet she conceives of herself as offering a critique of the liberal state as ‘male’. This is not so puzzling, however, once we realise that her critique is directed primarily against the pretensions of existing states, and the American state in particular, to what liberals call ‘neutrality’. Her target is the view – given its most drawn-out philosophical expression in the ‘political liberalism’ of the late John Rawls – that the state respects freedom through ‘non-intervention’ in matters deemed ‘private’. Attacking the so-called ‘negative state’ advocated by political liberalism, MacKinnon exposes the linguistic manoeuver of labelling ‘intervention’ only those exercises of state power thatchallenge the existing distribution of social privileges.[23] What appears as ‘inaction’, and therefore prima facie unproblematic from a liberal perspective, is the state’s role in enforcing thestatus quo: defining and administering the institution of marriage; refusing to fund reproductive healthcare; failing to prosecute those everyday rapes that do not threaten (and indeed help constitute) the prevailing order of which men own which women and which business is to be conducted where.

This is a familiar criticism, of course, going back to Marx’s dissection of the merely ‘political emancipation’ offered by liberal rights:

The state dissolves distinctions of birth, of social rank, of education, and of occupation if it declares birth, social rank, education, occupation, to be non-political distinctions; if without consideration of these distinctions it calls on every member of the nation to be an equal participant in the national sovereignty, if it treats all elements of the actual life of the nation from the point of view of the state. Nevertheless the state allows private property, education, occupation to function and affirm their particular nature in their own way, i.e. as private property, education, and occupation. Far from superseding these factual distinctions, the state’s existence presupposes them.[24]

Marx’s argument is mirrored in more recent criticisms, articulated by Charles Mills and Michelle Alexander, of the slippery ideology of ‘color-blindness’.[25] While ostensibly anti-racist, the ideal of just ‘not seeing race’ insidiously maintains white supremacy by erasing ‘the long history of structural discrimination that has left whites with the differential resources they have today, and all of its consequent advantages in negotiating opportunity structures’.[26] Refusing to recognise this history depoliticizes existing inequalities, which can then be blamed on individual choices. Similarly, MacKinnon argues, the state which purports to be ‘gender blind’ in fact ‘protects male power through embodying and ensuring existing male control over women at every level – cushioning, qualifying, or de jure appearing to prohibit its excesses when necessary to its normalization.De jure relations stabilize de facto relations’.[27] When asked to rectify this which it has done, the liberal state cries that this would violate the principle of ‘neutrality’.

MacKinnon’s analysis of sexual violence, then, aims to disrupt the familiar strategy of pointing to women’s ‘consent’ to legitimise an oppressively gendered status quo. While she does criticise the state as ‘male’, hers is a critique of the so-called ‘negative state’ – the state which seeks to preserve its ‘neutrality’ by leaving social domination untouched, while masking and legitimising it through the formal universality of law. Having dispensed with this liberal objection to wielding the law in women’s name, and exposed the extent to which the law is already involved in the administration of patriarchal social reality (‘non-intervention’ being an ideological cover for supporting the already-powerful), MacKinnon derives the urgent need for feminists to wield state power in the battle against sexual violence.[28]

1.3. The McCarthy in MacKinnon

Halley, like MacKinnon, holds that a radical feminist analysis of sexual violence (which they call the ‘subordination paradigm’) leads to Governance Feminism, although they take this connection to undermine the former rather than vindicate the latter.[29] The connection as they see it is essentially this: MacKinnon portrays women as so thoroughly subordinated, male domination as so total, sexual violence as so pervasive and devastating, that we need the state to save us. The basic argument derives from Wendy Brown’s critique of ‘identity politics’, and of MacKinnon for engaging in them.[30] Although the ‘identity politics’ label has often been used simply to dismiss struggles for emancipation that do not place the waged white hetero cis male subject at their centre, this is not how Brown uses it. Her concern is rather with the relation a struggle stands in to the liberal-bureaucratic state. Distinctive of identity politics, on her account, is the demand, directed towards the state, for legal recognition and protection (‘rights’) for a group defined as different andinjured.[31] Brown articulates two interrelated worries about identity politics, both of which she takes to apply to MacKinnon: (1) by being written into the ‘ahistorical rhetoric of the law and the positivist rhetoric of bureaucratic discourse’, identities which are, in fact, effects of social power are naturalised, while ‘the injuries contingently constitutive of them’ are reinscribed;[32] (2) in the process, the state is empowered and legitimised, forestalling possibilities for more radical transformation.[33]

If we look at the record of Governance Feminism, Brown’s worries seem well founded.[34] In any case, let us assume for the sake of argument that they are. The question is: in what ways, and to what extent, does a radical feminist analysis of sexual violence push us towards identity politics in this sense? Halley locates the source of Governance Feminism’s state-collaborationist tendencies in MacKinnon’s incessant focus on the sexual violation of women, accusing her of a ‘paranoid structuralism’ that denies women agency. For instance, Halley complains that:

Much contemporary feminist rape discourse repeatedly insists that the pain of rape extends into every future moment of a woman’s life; it is a note played not on a piano but on an organ.[35]

The implication is: rape is not so bad as the feminists say. Halley even encourages us to ask, ‘Why so many feminisms want women to experience themselves as completely devoid of choice when they bargain their way past a knife by having sex they really, really don’t want.’[36] The implication is: women have agency even when they are raped at knifepoint; it is not the rapists but the feminists who take their agency away.[37]

These quotations – and my pointedly crass glosses on them – of course do not capture the nuances of Halley’s position. Nonetheless, they highlight a strand in the critique of Governance Feminism that I am interested in because it reproduces the dilemma with which we began: state apologism or rape apologism.[38] Halley’s remarks, not only in content but in tone, foster the distinct impression that the critique of Governance Feminism is pursued at a price. What must be sacrificed, it seems, is the visceral commitment, which resonates throughout the writing of radical feminists like MacKinnon, to naming, theorising, and fighting against the myriad forms of sexual violence that constitute gender as we know it. To combat the state-affirming dangers of Governance Feminism, Halley seems to suggest, we need to (a)decentre ordownplay the problem of sexual violence in our analysis, and (b) regard women asmore free than the subordination paradigm suggests. These two points are clearly intertwined, since the question of whether, or to what extent, one is a victim of sexual violence is closely related to the question of whether, or to what extent, one’s sexual encounters are exercises of freedom.

As we have seen, MacKinnon takes freedom to require some measure of equality, conceived as the absence of hierarchy or domination. Halley rejects this. Indeed, they claim that MacKinnon’s formulation of freedom as incompatible with subordination is directly implicated in the ‘totalitarian trend visible in some feminist law reform proposals’.[39] Instead of freedom as (requiring) non-subordination,[40] Halley invokes the value of ‘agency’, which they illustrate with the following example.[41] Imagine a war-time situation in which an occupying army is committing atrocities against the local population. Under these circumstances, a woman might decide it is better to offer or supply under pressure sexual favours to a powerful soldier in exchange for food or protection from the sexual violence of other soldiers. In doing so she exercisesagency; she actively negotiates the power-relations in which she finds herself, shows courage and resourcefulness, and brings herself (or perhaps her family and friends) certain advantages.

On MacKinnon’s conception, this woman’s freedom is undermined because, however ingenious her survival strategies, it is still the case that she consents to, reluctantly submits to, or solicits sex in response to circumstances that are coercive; the soldier's power over the woman is the main reason that sex takes place. Halley argues that such a conception denies the woman’s agency, reducing her to a passive victim. Notice that there are two possible meanings of 'deny' in this context: firstly, one can deny that such-and-such is the case (e.g. denying that I can leave my prison cell because the door is locked); secondly, one can deny somethingto someone, that is, prevent them from having it (e.g. locking the cell door). Halley's claim is that denying women’s agency in the first sense – denyingthat women are exercising their freedom when, for example, they have sex to avoid violence they consider worse – has the consequence of denying women’s agency in the second sense – that is, preventing women from having agency.

We reach a familiar dilemma. On the one hand, there is a good deal of truth to the claim that MacKinnon presents a narrative of women as powerless. Particularly when written into the machinery of governance, this narrative does, plausibly, serve to undermine women’s attempts to negotiate, resist, re-signify, or subvert, (‘overthrow’ is not in Halley’s vocabulary, but perhaps it should be) the multifarious power relations to which we are subject. It thwarts our self-recognition as active agents rather than passive victims.On the other hand, Halley’s insistence on women’s agency seems to make us responsible even when we are coerced, which can sound a lot like victim-blaming. Indeed, anyone sympathetic to the radical feminist analysis of sexual violence will perceive this notion of ‘agency’ as steering perilously close to the old liberal notion of ‘consent’. Never mind how restrictive the options, never mind the pressures of socialization, never mind the threats for non-compliance, Halley seems to say, agency is there for the taking. Ironically, the only thing that appears effectively to undermine women’s agency, on Halley’s story, is Governance Feminism denying our agency. This can’t be right.

My modest preliminary suggestion is that some daylight needs to be inserted, in our political language, between the concepts ‘passive’ and ‘victim’. We should be suspicious of how easily the two words roll off the tongue together. Why should being a victim – being wronged, oppressed, subject to injustice – imply passivity? In one sense, it is clear why: something (wrong) is being done to you. Passivity is there in the grammar. Yet ‘passivity’ in the demeaning sense means something further: it means not showing courage, not making difficult decisions, not engaging in resistance; it means not being resilient, brilliant, inventive, or worthy of admiration. Must I declare myself passive in these ways simply to say that I am or have been victimised?

To some extent, yes – but only to some extent. It is a necessary part of criticising processes of dehumanisation to claim that, in a sense, they make us less than we could be; simply to exalt the qualities we develop under such conditions would be to naturalise our deformed state – as both Halley and MacKinnon criticise ‘cultural feminism’ for doing.[42] The problem is: as the debate is currently framed, looking that state square in the face seems to entail a plea for rescue by a state no less deformed. This is the inference I want to disrupt.[43] I make no pretence thereby to solve the dilemma – anything purporting to be an abstract resolution would be glib. However, I do hope to find some movement in what has come to seem a fixed set of options. In what follows, I will sketch three ways in which radical feminism’s commitment to challenging sexual violence, and MacKinnon’s analysis in particular, might be turned (against her own Governance Feminist tendencies) towards a politics more alert to the oppressions inherent in the state’s construction of the criminal.

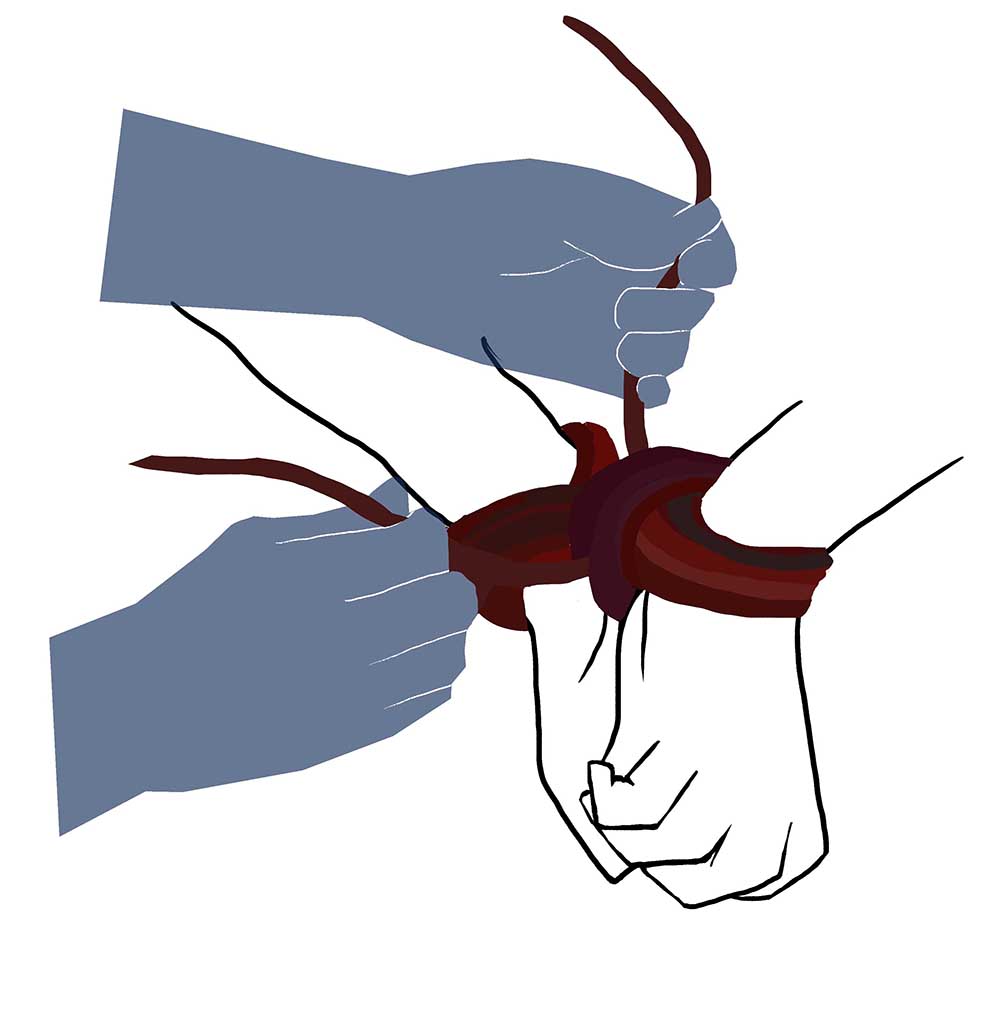

You are surrounded by an armed gang. They order you to remove your clothes. If you don't do as you're told – if you don't 'consent' – then they will forcibly remove your clothes. This means that they will pin you to the ground and use painful metal implements to prevent you from being able to move your arms and legs. They will tear your clothes off, or cut them off with scissors. They may use their weapons to make you comply, or punish you for not complying. Their weapons include truncheons and tasers, and sometimes guns. They may force your body into a position where they can peer inside your 'cavities' with a torch. They may insert their fingers, or even a whole hand, inside you.

Strip searching of arrestees by police is standard practice in the UK. Between 2013 and 2015, figures from 13 police forces in England and Wales show 113,000 strip searches, including 5,000 on children aged 17. The remaining 32 forces would not provide data in response to FOI requests by the BBC.[44] In the 2 years following the official end of routine strip searching of children in state institutions in 2011, over 40,000 such searches were recorded Almost half of these were perpetrated against children of colour. Illegal items were recovered on 15 occasions.[45]

Women at Yarl’s Wood detention centre, run by private security firm SERCO on behalf of the British Border Force, have spoken out repeatedly over the past decade about widespread sexual abuse by male guards.[46] Women involved in protests against fracking have complained of ‘sexualised intimidation’ by police.[47] Prisoners can still be forced to give birth in shackles and chains.[48] Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary has admitted that the hundreds of reported incidents of police officers using their authority to sexually coerce ‘domestic abuse victims, alcohol and drug addicts, sex workers and arrested suspects’ are probably just the tip of the iceberg, given the barriers to victims coming forward.[49] Riot police raiding suspected brothels in Soho bring journalists along to photograph the women they drag semi-naked onto the street, creating pornographic images of cowering women for distribution in the press.[50] Perhaps most explicitly of all, women who were tricked into sexual relationships with undercover police posing as left wing activists have said they feel 'raped by the state'.[51] These examples appear to show a liberal state relying on sexual violence perpetrated by its agents for the routine upholding of public order, private property, and the business of borders as usual – and that is before we even get to talking about what goes on when it wages war abroad. If there is any truth to this, then a commitment to challenging sexual violence gives us reason to distrust the state’s criminalizing power.[52]

Of course, some would deny that these are all instances of sexual violence. For instance, they might deny that strip-searching is sexual, and they might deny that it is violent – except in aberrant cases, and even then, they might say, prisoner non-compliance is generally to blame. To be clear, I do not claim that every strip search constitutes a sexual assault, but that strip searching as an institutional practicesystematically (i.e. often, and not accidentally) inflicts sexual violence on those who fall foul of the state. My suggestion is that MacKinnon’s analysis of sexual violence introduced in Part I can help us see this.

Firstly, consider the claim that a strip search cannot be a sexual assault because it is not sexual: it does not involve penises inside vaginas; if an officer has a hard-on, that is an accidental not an essential element of the process; not all officers even have penises; the motivation for strip-searching prisoners is not erotic enjoyment but the need to hunt for evidence or forbidden items. Now here is MacKinnon:

Like heterosexuality, male supremacy’s paradigm of sex, the crime of rape centers on penetration. The law to protect women’s sexuality from forcible violation and expropriation defines that protection in male genital terms. Women do resent forced penetration. But penile invasion of the vagina may be less pivotal to women’s sexuality, pleasure or violation, than it is to male sexuality. This definitive element of rape centers upon a male-defined loss.[53]

I do not see sexuality as a transcultural container, as essential, as historically unchanging, or as Eros. I define sexuality as whatever a given society eroticizes. That is, sexual is whatever sexual means in a particular society [...] In the society we currently live in, the content I want to claim for sexuality is the gaze that constructs women as objects for male pleasure. I draw on pornography for its form and content, for the gaze that eroticizes the despised, the demeaned, the accessible, the there-to-be-used, the servile, the child-like, the passive, and the animal.[54]

If a forcible strip search exactly mirrors – in the positioning of bodies, the script (‘There’s a good girl’), the props, the backdrop – scenes from violent pornography, that social fact must be understood as both reflecting and inflecting the meaning of the event. So too must the fact that CCTV cameras have been used to record strip-searches and broadcast them on monitors for other officers to view.[55] The regularity with which prisoners are strip searched in the absence of any reasonable suspicion that they are carrying forbidden items reveals its use as a tactic of intimidation and punishment, a show of power. To even make sense, this tactic depends upon the social meaning of being stripped naked, against one’s will, before strangers, as paradigmatically humiliating; the scene is a symbol of abjection. That is not to say it can never be subverted or resisted by individuals, but that this is the social meaning that attempts at subversion must address. On MacKinnon’s account, it would not undermine this analysis to say that many – even most – individual police officers carry out strip searches without the conscious intention of inflicting sexual violence. As she emphasises, most men who rape do not think of what they are doing under that description. Rapists tend to think that what they are doing is normal – and they are right, since it happens every day. They believe they are treating their victim as it is appropriate to treat that category of person – e.g. wife, slut, criminal. They are usually right that law courts will condone their perspective.[56]

It might be objected that many strip searches are carried out without overt violence. The Home Office guidelines state that ‘reasonable efforts should be made to secure a detainee’s cooperation’.[57] On MacKinnon’s analysis, however, this is hardly decisive. She argues that:

The deeper problem is that [we] are socialized to passive receptivity; may have or perceive no alternative to acquiescence; may prefer it to the escalated risk of injury and the humiliation of a lost fight; submit to survive.[58]

Compare this with Laura Whitehorn’s recollection of her time in prison:

For me, one of the most damaging and nearly invisible forms of sexual abuse was the daily pat-searches by male guards. On a regular basis in my years in federal prisons, I was forced to stand still and allow men to touch my body in ways that would have automatically provoked me to fight back if I had been outside of prison. But as long as I was labeled with that federal prison number, such self-defense would have gotten me an assault charge adding five years to my sentence. (Repeated legal challenges have proved unable to stop this practice in federal prisons.)[59]

When women are sexually assaulted outside the walls of prisons and police stations, submitting to survive is interpreted as consent.[60] When we are sexually assaulted inside, not only is submitting to survive seen as erasing the violence of the encounter, but not being submissive enough provides legal grounds for an escalation of force.

Not resisting means that what happens does not count as violence; resisting means asking for it.

Vulnerability to sexual violence, MacKinnon emphasises, is not a ‘natural’ feature of women, but a product of unjust circumstances, such as not being able to leave an abusive partner or stand up to an abusive boss because you are economically dependent on him.[61] Indeed, on MacKinnon’s account, coercive circumstances can render a sexual encounter violent, even if no blows are struck. Coercion is a matter of counterfactuals. It is a matter of knowing what would happen if you were to defy an order, or decline an ‘invitation’: if I were to fight back, he would beat me up; if I were to refuse him, he would fire me; if I were to leave him, I would be homeless, my children would be taken into care, I would be deported, and so on.

In her critique of liberal ‘neutrality’, MacKinnon points to the state’s role in upholding coercive circumstances, for instance through divorce laws which systematically disadvantage women by devaluing the contribution of domestic and caring labour to the household economy. However, there is a more basic point that she repeatedly overlooks: all economic power, including that of men over women, depends upon the enforcement of property. That enforcement is carried out, in the final analysis, by the criminalizing state. The liberal state’s enforcement of property, through violence or the threat of violence, is therefore partly constitutive of male domination. Let me put this less abstractly. In 2015, theft offences accounted for 49% of all prison sentences handed out to women in England and Wales. 46% of women in prison report having suffered domestic violence.[62] These are only the cases where the state’s threat is carried out. The counterfactual, though, inflects every decision. If I were to refuse him, I would have no money for food, or nappies for my children; if I were to take food or nappies without paying for them, I would risk arrest and imprisonment.

Of course, for liberals, this is still the ‘negative state’, because it is definitive of liberalism to take the property-enforcing function of the state for granted. MacKinnon insists that the state maintains male domination even in its negative mode because ‘men’s forms of dominance over women have been accomplished socially as well as economically, prior to the operation of law, without express state acts, often in intimate contexts, as everyday life’.[63] The problem is, this still grants too much weight to the liberal misnomer ‘negative’. Economic domination does not occur ‘prior to the operation of law’. Locking women up for shoplifting or for handling stolen goods is an operation of law, albeit an everyday one, upon which the operation of the economy depends. Neglecting the way women are kept in line bythe state’s activity of criminalizing transgressions of the order of property allows MacKinnon’s critique of the negative state to slide into advocacy of a ‘positive’ or ‘interventionist’ state.

This slippage may be party explained by a blind-spot in MacKinnon’s understanding of the historically available options for thinking about the state. In defending her own ‘positive state’ solution to the strategic question, she positions herself against two alternative accounts. The first is the liberal account already considered. The second, which she calls ‘Marxist’, is an account of the state as ‘superstructural’, hence (on MacKinnon’s vulgar reading) ‘epiphenomenal’ – which means that it does not make a difference to anything. As she puts it:

The liberal view that law is society’s text, its rational mind, expresses the male view in the normative mode; the traditional left view that the state, and with it the law, is superstructural or epiphenomenal, expresses it in the empirical mode. A feminist jurisprudence, stigmatized as particularized and protectionist in male eyes of both traditions, is accountable to women’s concrete conditions and to changing them.[64]

Even leaving aside from the problems with this as a reading of Marx, what MacKinnon erases here is the possibility that the state is actually effective as an oppressive force. This erasure serves to naturalise women’s oppression by obscuring a key means by which it is – artificially – maintained. Yet, I have argued, MacKinnon’s own account of coercive conditions makes clear how vulnerability to sexual violence can be generated by the enforcement of a system of property relations in which women systematically lose out. The slide into Governance Feminism might be halted if she followed through on this insight.

According to Halley, MacKinnon’s critique of consent, which corresponds to her account of freedom as (requiring) non-subordination, results directly in a statism that disregards and even impedes women’s agency. In this final section, I want to suggest that MacKinnon’s trenchant excavation of the myriad ways in which a context of subordination renders our choices unfree can in fact be seen to undermine the liberal state’s account of its own legitimacy.

The point can be put quite schematically. Liberalism means liberal capitalism; the liberal state maintains a capitalist economy. Capitalism is based on wage-labour, that is, the sale of labour power as a commodity. I sell my labour power to someone else, who (if all goes well) exploits me to make a profit. The reason I sell them my labour power is because otherwise I don't have any way of living, or certainly of living decently (a core function of the state being to prevent me from using things I cannot pay for). The reason I sell my labour power to them, and not vice versa, is because of a crucial disparity between us: they own the means of make useful things, things to satisfy human wants and needs, while I do not. I therefore contract – ‘consent’ – to be exploited by them, my other option being to starve on the streets.[65] This is, of course, the ‘double freedom’ to which Marx satirically refers:

[The free worker] must be free in the double sense, that as a free individual he can dispose of his labour-power as his own commodity, and that on the other hand he has no other commodity for sale, i.e. he is rid of them, he is free of all the objects needed for the realisation [Verwirklichung] of his labour-power.[66]

Now, it is crucial for liberalism that the labour contract remain valid, and that I count as free when I ‘consent’ to it. No matter how much any particular liberal might want to regulate markets, or support state redistribution, they cannot give up on this, otherwise they would be giving up on the claim that we could, in principle, reach an acceptable level of freedom under capital. Then they would no longer be a liberal in the relevant sense (although they might be holding to the more emancipatorystrands of liberalism’s contradictory inheritance).[67] Maintaining the validity of the wage labour contract, however, depends precisely on ignoring those material and ideological constraints on freedom exposed by MacKinnon’s critique of the patriarchal concept of consent. The basic power imbalance between me and my would-be boss (constituted by our owning and not owning means of production, respectively, and my subsequent dependence on him for survival) would be enough, on her account, to vitiate much of the normative force of my reluctant submission. That's before we even start talking about ideology and social construction, about the ways in which productive, compliant capitalist subjects are moulded.

In fact, it is unsurprising that MacKinnon’s conception of freedom should undermine the validity of the capitalist labour contract, since she deliberately invokes the Marxist critique of liberal freedom to make what is often seen as her most controversial point:

Most people see sexuality as individual biological and voluntary; that is, they see it in terms of the politically and formally liberal myth structure. If you applied such an analysis to the issue of work [...] would you agree, as people say about heterosexuality, that a worker chooses to work? Does a worker even meaningfully choose his or her specific line or place of work? If working conditions improve, would you call that worker not oppressed? If you have a comparatively good or easy or satisfying or well-paying work, if you like your work, or have a good day at work, does that mean, from a marxist perspective, your work is not exploited? Those who think that one chooses heterosexuality under conditions that make it compulsory should either explain why it is not compulsory or explain why the word choice can be meaningful here.[68]

It is ironic that MacKinnon’s analysis should so often be taken to support the view that sex workers are uniquely unfree and need to be rescued by the very state which enforces the property relations constitutive of all workers’ unfreedom. It will hardly suffice to respond that we ‘consent’ to the government which enforces these conditions, as social contract theory seeks to do. Given the massive power imbalance, the pressures of socialization, and the threats for non-compliance, MacKinnon might say, ‘the issue is less whether there was force than whether consent is a meaningful concept’.[69]

Conclusion

By refusing the demand to pick a side when the construction of sides is itself part of the trap, hoping instead to fracture the received framework of options and allegiances, this intervention into the Governance Feminism debate has been an experiment inimpure thinking. It reflects my conviction that such thinking is required if we are to escape the identitarian fly-bottle in whose distorting walls each person’s reflection appears asone unchanging essence: either ally or apologist.[70] It will have been successful insofar as I have convinced some radical feminists to listen to critics of carceral politics rather than dismissing them as rape apologists, and some critics of carceral politics to listen to radical feminists rather than dismissing them as state apologists – even though both accusations contain elements of truth. Precisely because everyone is guilty of something, the prosecutorial mode of engagement will not get us very far.

Questioning the presuppositions of the debate’s usual set-piece, I have argued that taking sexual violence seriously, as per the radical feminist analysis, need not entail support for state-power-wielding strategies. On the contrary, following through that analysis shows real existing liberal states in a pretty dim light. The punitive state emerges as not merely an inadequate protector, but as itself a perpetrator – perhaps the biggest single perpetrator – of sexual violence. An advocate of Governance Feminism might say that this simply adds ammunition to MacKinnon’s critique of the state as ‘male’. Rather than telling against Governance Feminism, they might say, it shows the urgent need to reform the liberal state ‘from within’. Of course, there is no simple dichotomy between within and without. To target our efforts at tempering or counter-balancing the abjectifying powers of police, border, and prison officials would already be a significant and welcome departure from the trajectory of feminism-as-crime-control, even while we might work in part through legal channels. I have suggested, though, that MacKinnon’s account of ‘coercive circumstances’, considered in relation to the capitalist order of (exploitative) work and (vastly unequal) property, gives us cause to be sceptical about the liberal state’s capacity for positive transformation. That does not vitiate all strategies that work ‘with’ or ‘within’ the state. They may create vital breathing space for more radical alternatives. It does require, though, that we be clear-sighted about their limitations.

This point is very different from the standard liberal objection to ‘state intervention’. That objection points to the 'coerciveness' of the state as a reason against using the law to fight oppression, and criticises proposed feminist and anti-racist reforms as dangerous and 'totalitarian'. The liberal concern about the state’s 'coerciveness', however, emerges only when the state goes beyond those basic functions I described earlier. As we have seen, liberals tend not to think of the state as acting or interveningat all when it maintains existing property and power relations.My concerns about the institutionally rapist character of existing states, on the other hand – which I have suggested MacKinnon’s analysis of sexual violence itself gives us reason to take seriously – do not apply only or even primarily to proposed feminist departures from what passes for ‘state neutrality’ (though they point towards ways these efforts may, if we are not careful, be counter-productive). Rather, they suggest that challenging domination for all those subordinated by gender, not just a white, affluent, and obedient few, will require us to direct our critical attentions at precisely the criminalizing activities of liberal states which constitute business as usual. They suggest, in other words, that we need to make feminism ungovernable.

BACK TO ISSUE 26(2): IDENTITY POLITICS

References

Adorno, Theodor W. Negative Dialectics. Translated by E. B. Ashton. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1973.

Agustin, Laura. Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets and the Rescue Industry. London: Zed Books, 2007.

Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press, 2011.

Barbagallo, Camille. ‘Leaving Home: Slavery and the Politics of Reproduction’. Viewpoint Magazine, 31 October 2015. https://www.viewpointmag.com/2015/10/31/leaving-home-slavery-and-the-politics-of-reproduction/.

Bernstein, Elizabeth. ‘Carceral Politics as Gender Justice? The “Traffic in Women” and Neoliberal Circuits of Crime, Sex, and Rights’. Theory and Society 41, no. 3 (2012): 233–59.

———. ‘Militarized Humanitarianism Meets Carceral Feminism: The Politics of Sex, Rights, and Freedom in Contemporary Anti-Trafficking Campaigns’. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society Special Issue on Feminists Theorize International Political Economy, Guest-edited by Kate Bedford and Shirin Rai, no. 36, 1 (2010).

Brown, Wendy. States of Injury: Power and Freedom in Late Modernity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Brown, Wendy, and Janet Halley, eds. Left Legalism/Left Critique. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002.

Chen, Ching-In, Jai Dulani, and Piepzna-Samarasinha Leah Lakshmi, eds. The Revolution Starts at Home: Confronting Intimate Violence Within Activist Communities. Brooklyn, NY; Boston, MA: South End Press, 2011.

Clinks. ‘Key Facts’. Registered charity. Women’s Breakout: Chances to Change, 2017. http://womensbreakout.org.uk/about-womens-breakout/key-facts/.

Dalla Costa, Mariarosa. Women and the Subversion of the Community: A Mariarosa Dalla Costa Reader. Edited by Camille Barbagallo. Oakland, CA: AK Press, Forthcoming.

Davis, Angela. Are Prisons Obsolete? New York: Seven Stories, 2003.

———. ‘Racism, Birth Control and Reproductive Rights’. In Women, Race & Class, 202–21. London: The Women’s Press, 1981.

Duff, Koshka. ‘Review of “Living Less Wrongly: Adorno’s Practical Philosophy” by Fabian Freyenhagen and “Adorno” by Brian O’Connor’. Marx and Philosophy Society Review of Books, 2014. http://www.marxandphilosophy.org.uk/reviewofbooks/reviews/2014/948.

———. ‘The Criminal Is Political: Policing Politics in Real Existing Liberalism’. Journal of the American Philosophical Association 3, no. 4 (2017): 485–502.

Federici, Sylvia. Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2012.

Finlayson, Lorna. ‘How to Screw Things with Words: Feminism Unrealized’. In The Political Is Political: Conformity and the Illusion of Dissent in Contemporary Political Philosophy, 89–111. London: Rowman & Littlefield International, 2015.

———. Introduction to Feminism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction. Translated by Robert Hurley. Originally published in French by Editions Gallimard, Paris, 1976. New York: Vintage Books, 1980.

Gayle, Damien. ‘Police “Used Sexualised Violence against Fracking Protesters”’. The Guardian, 23 February 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/feb/23/fracking-police-sexualised-violence-barton-moss-protest.

Gentleman, Amelia, and Damien Gayle. ‘Sarah Reed’s Mother: My Daughter Was Failed by Many and I Was Ignored’. The Guardian, 17 February 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/feb/17/sarah-reeds-mother-deaths-in-custody-holloway-prison-mental-health.

Ginn, Stephen. ‘Women Prisoners’. BMJ 346:e8318 (January 2013).https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8318.

Goldberg, Adrian. ‘The Girl Who Was Strip-Searched Aged 12 by Police’. BBC News, 30 October 2016. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-37801760.

Grierson, Jamie. ‘Hundreds of Police in England and Wales Accused of Sexual Abuse’. The Guardian, 8 December 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/dec/08/hundreds-police-officers-accused-sex-abuse-inquiry-finds.

Halley, Janet. ‘Rape in Berlin: Reconsidering the Criminalisation of Rape in the International Law of Armed Conflict’. Melbourne Journal of International Law 9, no. 1 (2008): 78–124.

———. Split Decisions: How and Why to Take a Break from Feminism. Princeton University Press, 2008.

Halley, Janet, Prabha Kotiswaran, Hila Shamir, and Chantal Thomas. ‘From the International to the Local in Feminist Legal Responses to Rape, Prostitution/Sex Work, and Sex Trafficking: Four Studies in Contemporary Governance Feminism.’ Harvard Journal of Law & Gender 29 (2006): 336–423.

Hanhardt, Christina. Safe Space: Gay Neighbourhood History and the Politics of Violence. New York: Duke University Press, 2014.

Jenkins, Katharine. ‘Amelioration and Inclusion: Gender Identity and the Concept of Woman’. Ethics 126, no. 2 (2016): 394–421.

Lamble, Sarah. ‘Queer Necropolitics and the Expanding Carceral State: Interrogating Sexual Investments in Punishment’. Law and Critique 24, no. 3 (2013).

Langton, Rae. Sexual Solipsism: Philosophical Essays on Pornography and Objectification. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Law, Victoria. ‘Against Carceral Feminism’. Jacobin (Online), 17 October 2014.https://www.jacobinmag.com/2014/10/against-carceral-feminism/.

———. Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women. 2nd Edition. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2012.

MacKinnon, Catharine. Are Women Human? And Other International Dialogues. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007.

———. Feminism Unmodified: Discourses on Life and Law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

———. Toward a Feminist Theory of the State. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

MacKinnon, Catharine. Butterfly Politics. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017.

Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Translated by Ben Fowkes. Vol. 1. London: Penguin, 1976.

———. ‘On the Jewish Question’. In Early Political Writings, edited by Joseph J. O’Malley, 28–56. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Mills, Charles. ‘White Ignorance’. In Race and Epistemologies of Ignorance, edited by Shannon Sullivan and Nancy Tuana, 11–38. New York: SUNY Press, 2007.

Molloy, Parker Marie. ‘CeCe McDonald: Rebuilding Her Life after 19 Months in Prison’. Advocate, 3 March 2014. https://www.advocate.com/politics/transgender/2014/03/03/cece-mcdonald-rebuilding-her-life-after-19-months-prison%20.

O’Connor, Brian. Adorno (The Routledge Philosophers). Oxford: Routledge, 2013.

Pollak, Sorcha. ‘Trauma of Spy’s Girlfriend: “Like Being Raped by the State”’. The Guardian, 24 June 2013. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2013/jun/24/undercover-police-spy-girlfriend-child.

Ritchie, Andrea J. Invisible No More: Police Violence against Black Women and Women of Color. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2017.

Roberts, William Clare. Marx’s Inferno: The Political Theory of Capital. New York: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Sambrook, Clare. ‘Strip-Searched in Derbyshire’. Open Democracy, 1 October 2013. https://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/clare-sambrook/strip-searched-in-derbyshire.

Smith, Molly. ‘Soho Police Raids Show Why Sex Workers Live in Fear of Being “Rescued”’. The Guardian, 11 December 2013. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/dec/11/soho-police-raids-sex-workers-fear-trafficking.

Sudbury, Julia, ed. Global Lockdown: Race, Gender and the Prison-Industrial Complex. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Sunstein, Cass. ‘Neutrality in Constitutional Law (with Special Reference to Pornography, Abortion, and Surrogacy)’. Columbia Law Review 92, no. 1 (1992): 1–52.

Taylor, Diane. ‘Dossier Calling for Yarl’s Wood Closure Chronicles Decades of Abuse Complaints’. The Guardian, 15 June 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/jun/15/yarls-wood-report-calling-for-closure-decade-abuse-complaints.

Threadcraft, Shatema. ‘Intimate Injustice, Political Obligation, and the Dark Ghetto’. Signs 39, no. 3 (2014): 735–60.

Ticktin, Miriam. ‘Sexual Violence as the Language of Border Control: Where French Feminist and Anti-Immigrant Rhetoric Meet’. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 33, no. 4 (2008): 863–89.

Wang, Jackie. ‘Against Innocence: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Safety’. Lies: A Journal of Materialism Feminism 1 (2012).

Willow, Carolyne. ‘Many Thousands of Children Stripped Naked in Custody. Ignites Memories of Being Raped.’ Open Democracy, 4 March 2013. https://www.opendemocracy.net/shinealight/carolyne-willow/many-thousands-of-children-stripped-naked-in-custody-ignites-memories-of.

Young, Iris Marion. ‘Gender as Seriality: Thinking about Women as a Social Collective’. Signs 19, no. 3 (1994): 713–38.

———. Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Various. ‘Community Accountability: Emerging Movements to Transform Violence’. A Special Issue of Social Justice: A Journal of Crime, Conflict & World Order 37, no. 4 (2012 2011).

* The author would like to thank the following for formative conversations and comments on earlier drafts: Dara Bascara, Camille Barbagallo, Lucy Beynon, Melanie Brazzell, Anja Büchele, Debaleena Dasgupta, Gloria Dawson, Marijam Didžgalvytė, Lorna Finlayson, Miranda Glossop, Matthew Hall, Maham Hashmi, Amelia Horgan, Becka Hudson, Shruti Iyer, Katharine Jenkins, Lisa Jeschke, Louise Lambe, Helen Lynch, Liz Maxwell, Rowan Milligan, Kate Paul, Ambar Sethi, Laurel Uziell, Rosalind Worsdale, and several anonymous reviewers at this journal.

[1] Jackie Wang argues powerfully against making solidarity conditional on ‘innocence’, as defined by existing institutions under conditions of injustice. See ‘Against Innocence: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Safety’, Lies: A Journal of Materialism Feminism 1 (2012).

[2] This is a simplification in several ways. Firstly, there in not just one state – ‘the state’ – but many. My concern is primarily with the states of Western Europe and their former settler colonies (so-called ‘liberal democracies’) while recognising that the operations of these states often are intertwined with, and depend economically upon, those of other kinds of states, such as China and Saudi Arabia. Secondly, this is a simplification because it ignores the question of how international law and paralegal institutions such as NGOs, which often operate internationally, relate to processes of state power. Nonetheless, my point is that mainstream discourse assumes that the struggle against sexual violence must rely upon the punitive – i.e. criminalizing, sanctioning, punishing – functions of existing liberal states and their satellites or proxies. When I speak of ‘state-power-wielding strategies’, I mean punitive state power. Of course, separating punitive from other state functions, such as resource provision – insofar as that is made conditional on compliance – is no simple matter. On this, seeShatema Threadcraft, ‘Intimate Injustice, Political Obligation, and the Dark Ghetto’, Signs 39, no. 3 (2014): 735–60.

[3]Elizabeth Bernstein, ‘Carceral Politics as Gender Justice? The “Traffic in Women” and Neoliberal Circuits of Crime, Sex, and Rights’, Theory and Society 41, no. 3 (2012): 251. This is not to say that feminists have always accepted this brief. For accounts of some alternative responses to sexual violence, including ‘community accountability’ and ‘transformative justice’ projects, see: Ching-In Chen, Jai Dulani, and Piepzna-Samarasinha Leah Lakshmi, eds., The Revolution Starts at Home: Confronting Intimate Violence Within Activist Communities (Brooklyn, NY; Boston, MA: South End Press, 2011); Various, ‘Community Accountability: Emerging Movements to Transform Violence’,A Special Issue of Social Justice: A Journal of Crime, Conflict & World Order 37, no. 4 (2012 2011).

[4]Janet Halley, Split Decisions: How and Why to Take a Break from Feminism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006), 340.

[5]Bernstein, ‘Carceral Politics as Gender Justice?’, 251. While recognising that they are not exactly equivalent, I will be using the terms ‘Governance Feminism’, ‘carceral feminism’, and ‘feminism-as-crime-control’ largely interchangeably.

[6]Bernstein, 249. See also: Laura Agustin, Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets and the Rescue Industry (London: Zed Books, 2007); Christina Hanhardt,Safe Space: Gay Neighbourhood History and the Politics of Violence (New York: Duke University Press, 2014); Sarah Lamble, ‘Queer Necropolitics and the Expanding Carceral State: Interrogating Sexual Investments in Punishment’,Law and Critique 24, no. 3 (2013); Miriam Ticktin, ‘Sexual Violence as the Language of Border Control: Where French Feminist and Anti-Immigrant Rhetoric Meet’,Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 33, no. 4 (2008): 863–89.

[7]Wendy Brown, States of Injury: Power and Freedom in Late Modernity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995).

[8] MacKinnon does not call herself a ‘radical feminist’, preferring to call her approach ‘feminism’ simpliciter, or ‘feminism unmodified’. See Feminism Unmodified: Discourses on Life and Law (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987). However, she is referred to in this way often enough for the label to be of some use. For helpful discussion of controversy around the term see ‘Faces and Facades’, in Lorna Finlayson, Introduction to Feminism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 82–100. Of course, radical feminism is known for its tendency to exclude of trans women and sex workers. I will touch on these exclusions insofar as they relate to problems of criminalisation and agency, but clearly there is much more to be said. The partial and critical re-appropriation of MacKinnon I propose should not be taken to imply any endorsement of trans or sex worker exclusionary positions.

[9] See Rae Langton, Sexual Solipsism: Philosophical Essays on Pornography and Objectification (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

[10] For critical discussion of this trend, see Lorna Finlayson, ‘How to Screw Things with Words: Feminism Unrealized’, in The Political Is Political: Conformity and the Illusion of Dissent in Contemporary Political Philosophy (London: Rowman & Littlefield International, 2015), 89–111.

[11] Particularly in her earlier work, MacKinnon was keen to emphasise the difference between ‘empowering the state, as criminal law does’ (and as she, at the time of the notorious Minneapolis Ordinance against pornography, in fact opposed), and civil law remedies, which she hoped might ‘put more power in the hands of women both to confront the state [...] and to directly confront men in society who harm them’ (Are Women Human? And Other International Dialogues (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007), 33. How seriously she took this proviso is questionable. In more recent decades, she has focused her interventions on international legal institutions. Her associations with both US and Israeli state forces are traced in Lorna Finlayson’s review (‘Butterfly Torture’, London Review of Books, forthcoming) of MacKinnon’s latest collection, Butterfly Politics (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017).

[12]Theodor W. Adorno, Negative Dialectics, trans. E. B. Ashton (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1973).

[13] This claim is far from unique to MacKinnon. Cf. Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (London: Routledge, 1990); Monique Wittig,The Straight Mind and Other Essays (London: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1992); Michel Foucault,The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction (Vintage, 1990).

[14]Catharine MacKinnon, Toward a Feminist Theory of the State, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), 113.

[15] One issue is important to flag at the outset. MacKinnon speaks primarily of women being harmed by sexual violence. Insofar as I will be adopting her language, ‘women’ should be understood as including all trans and cis women. However, there is still a danger of erasing many people who are systematically targeted for sexual violence precisely because they do not conform to the categories of binary gender, or because they were assigned female at birth. Given the role MacKinnon attributes to sexual violence in constructing and policing gender categories, she should be attentive to this problem, but her relentlessly binary language can rightly be criticised for perpetuating it. On the other hand, I do not think we can do away with ‘woman’ as a political category while gender persists as a system of oppression. I find helpful Iris Marion Young’s concept of ‘gender as seriality’, and Katharine Jenkins’s distinction between ‘gender as class’ and ‘gender as identity’. See:Iris Marion Young, ‘Gender as Seriality: Thinking about Women as a Social Collective’, Signs 19, no. 3 (1994): 713–38; Katharine Jenkins, ‘Amelioration and Inclusion: Gender Identity and the Concept of Woman’,Ethics 126, no. 2 (2016): 394–421.

[16] In an over-sight typical of white feminism, she spends less time talking about forced sterilization. Cf. Angela Davis, ‘Racism, Birth Control and Reproductive Rights’, in Women, Race & Class (London: The Women’s Press, 1981), 202–21.

[17] This is the term MacKinnon uses for sex work.

[18]MacKinnon, Toward a Feminist Theory of the State, xi.

[19]MacKinnon, 175.

[20] This aspect of MacKinnon’s argument has been persuasively developed by Rae Langton. See Sexual Solipsism: Philosophical Essays on Pornography and Objectification.

[21]MacKinnon, Toward a Feminist Theory of the State, 168.

[22]MacKinnon, 124.

[23] This point is also made in: Cass Sunstein, ‘Neutrality in Constitutional Law (with Special Reference to Pornography, Abortion, and Surrogacy)’, Columbia Law Review 92, no. 1 (1992): 1–52; Iris Marion Young,Justice and the Politics of Difference (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990).

[24]Karl Marx, ‘On the Jewish Question’, in Early Political Writings, ed. Joseph J. O’Malley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 35.

[25]Charles Mills, ‘White Ignorance’, in Race and Epistemologies of Ignorance, ed. Shannon Sullivan and Nancy Tuana (New York: SUNY Press, 2007), 11–38; Michelle Alexander,The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2011).

[26]Mills, ‘White Ignorance’, 28.

[27]MacKinnon, Toward a Feminist Theory of the State, 167.

[28] She also briefly considers what she (spuriously) takes to be the leftist alternative: epiphenomenalism – i.e. the view that the state is a causally inert by-product of an ‘economic base’. I will come to this in section 2.2.

[29] Halley does allow that ‘governance feminism has been, in manifold ways, a good thing’ (Split Decisions: How and Why to Take a Break from Feminism, 33.

[30]Brown, States of Injury.

[31] A group engaged in ‘identity politics’ in Brown’s sense might be white, waged, etc. - as with the ‘blue Labour’ identity politics of ‘British jobs for British workers’.

[32]Brown, States of Injury, 28.

[33] MacKinnon is not unaware of these dangers. For instance, she criticises various legal protections for women workers on these grounds: ‘Concretely, it is unclear whether these special protections, as they came to be called, helped or hurt women. These cases did do something for some workers (female) concretely; they also demeaned all women ideologically. They did assume that women were marginal and second-class members of the workforce; they probably contributed to keeping women marginal and second-class workers by keeping some women from competing with men at the male standard of exploitation.’ (MacKinnon, Toward a Feminist Theory of the State, 165.) However, Brown and Halley argue that her own approach inadvertently replicates this problem.

[34] As well as works cited already, see Julia Sudbury, ed., Global Lockdown: Race, Gender and the Prison-Industrial Complex (New York: Routledge, 2005).

[35]Halley, Split Decisions: How and Why to Take a Break from Feminism, 354.

[36]Halley, 355.

[37] The context is a case in which the woman describes herself as having been raped. Halley offers a creative re-reading. Therefore, it is not that Halley is more committed than MacKinnon to respecting a woman’s description of her own experience. Both, in fact, are attentive to the ways that existing social narratives and legal institutions may influence our self-presentation and even self-understanding.

[38] Halley is not the only critic of Governance Feminism to treat her opponent’s concerns – and even experiences – with a certain callousness. For instance, Bernstein reports an anti-prostitution activist, Chyng Sun, making the (surely correct) point that commercial sex and pornography also affect women not working in the industry by setting standards for ‘how all women “should look, sound, and behave”’, and another author, Kristen Anderberg, ‘describing how watching pornographic videos with her male lover lead to debilitating body issues and to plummeting self esteem’. Bernstein diagnoses these women as, essentially, jealous frumps ‘harbour[ing] a set of investments in “family values” and home’, and threated by a ‘recreational’ sexual ethic. (Bernstein, ‘Carceral Politics as Gender Justice?’, 245.)

[39]Halley, Split Decisions: How and Why to Take a Break from Feminism, 125.

[40] MacKinnon is clear that non-subordination is a necessary condition for freedom, but not committed to the claim that it is sufficient. Freedom and non-subordination are not presented as equivalent.

[41] Halley takes the example from the anonymous memoir, A Woman in Berlin. SeeJanet Halley, ‘Rape in Berlin: Reconsidering the Criminalisation of Rape in the International Law of Armed Conflict’, Melbourne Journal of International Law 9, no. 1 (2008): 78–124.

[42] Cultural feminism, in Halley’s words, emphasises ‘unjust male derogation of women’s traits’, and ‘reserve[s] a special place for the redemptive normative insights that women derive from their sexuality and their role as mothers’. Halley, Split Decisions: How and Why to Take a Break from Feminism, 27–28.

[43] William Clare Roberts makes a parallel point in his exposition of Capital Volume 1, in response to the objection that Marx denies agency to proletarians: ‘The significance of [Marx’s] comments about individuals in modern commercial society being bearers of economic relations is not that these individuals suffer an impairment of their agency, but that they suffer an impairment of theirfreedom. Commodity producers in a commercial society aredominated agents, not nonagents [...] If domination leaves freedom intact, then there is no such thing as domination [...] Marx does not argue that economic relations manipulate individuals like puppets, but that economic relations dominate their decision making.’ (William Clare Roberts, Marx’s Inferno: The Political Theory of Capital (New York: Princeton University Press, 2016), 95.)

[44]Adrian Goldberg, ‘The Girl Who Was Strip-Searched Aged 12 by Police’, BBC News, 30 October 2016, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-37801760.

[45]Carolyne Willow, ‘Many Thousands of Children Stripped Naked in Custody. Ignites Memories of Being Raped.’, Open Democracy, 4 March 2013, https://www.opendemocracy.net/shinealight/carolyne-willow/many-thousand…. The same report notes that many searches go unrecorded.

[46]Diane Taylor, ‘Dossier Calling for Yarl’s Wood Closure Chronicles Decades of Abuse Complaints’, The Guardian, 15 June 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/jun/15/yarls-wood-report-calli….

[47]Damien Gayle, ‘Police “Used Sexualised Violence against Fracking Protesters”’, The Guardian, 23 February 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/feb/23/fracking-police-sexuali….

[48]Stephen Ginn, ‘Women Prisoners’, BMJ 346:e8318 (January 2013),https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8318.

[49]Jamie Grierson, ‘Hundreds of Police in England and Wales Accused of Sexual Abuse’, The Guardian, 8 December 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/dec/08/hundreds-police-officer….

[50]Molly Smith, ‘Soho Police Raids Show Why Sex Workers Live in Fear of Being “Rescued”’, The Guardian, 11 December 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/dec/11/soho-police-raids….

[51]Sorcha Pollak, ‘Trauma of Spy’s Girlfriend: “Like Being Raped by the State”’, The Guardian, 24 June 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2013/jun/24/undercover-police-spy-girlfr….

[52] I focus on the British context partly because it is the state with which I am most familiar, and partly to pre-empt the complacent ‘Things are different here!’ response so often given to US examples. For examination of the US context, see ‘Police Sexual Violence’ in Koshka Duff, ‘The Criminal Is Political: Policing Politics in Real Existing Liberalism’, Journal of the American Philosophical Association 4, no. forthcoming (2018). and ‘How Gender Structures the Prison System’ in Angela Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete? (New York: Seven Stories, 2003). For international examples, see Sudbury, Global Lockdown: Race, Gender and the Prison-Industrial Complex.

[53]MacKinnon, Toward a Feminist Theory of the State, 172.

[54]MacKinnon, Feminism Unmodified, 53–54.

[55]Clare Sambrook, ‘Strip-Searched in Derbyshire’, Open Democracy, 1 October 2013, https://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/clare-sambrook/strip-searched-….

[56] There are occasional prosecutions of police officers for other forms of sexual abuse. We might map this onto MacKinnon’s argument that sexual violence, although not in practice prohibited, is regulated just enough to uphold the social order’s appearance of legitimacy. To the best of my knowledge, there have been no prosecutions for strip searching.

[57]Goldberg, ‘Strip-Searched Aged 12’.

[58]MacKinnon, Toward a Feminist Theory of the State, 177.

[59]Victoria Law, Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women, 2nd Edition (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2012), vi.

[60] Women may also be criminalized for defying the demands of femininity by putting up resistance – women of colour being disproportionately targeted in this way. Cases that have received some publicity include Sarah Reed, who died while on remand in HMP Holloway awaiting trial for defending herself against sexual assault, and Ce Ce McDonald, imprisoned for defending herself against a transphobic attack. See: Amelia Gentleman and Damien Gayle, ‘Sarah Reed’s Mother: My Daughter Was Failed by Many and I Was Ignored’, The Guardian, 17 February 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/feb/17/sarah-reeds-mother-deat…; Parker Marie Molloy, ‘CeCe McDonald: Rebuilding Her Life after 19 Months in Prison’, Advocate, 3 March 2014,https://www.advocate.com/politics/transgender/2014/03/03/cece-mcdonald-….

[61] There is an important Marxist-feminist literature theorising gendered economic dependence and struggles against it, as well as the relations of these to various facets of the state. The analysis presented here has been informed especially by the following: Sylvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2012); Camille Barbagallo, ‘Leaving Home: Slavery and the Politics of Reproduction’, Viewpoint Magazine, 31 October 2015,https://www.viewpointmag.com/2015/10/31/leaving-home-slavery-and-the-po…; Mariarosa Dalla Costa,Women and the Subversion of the Community: A Mariarosa Dalla Costa Reader, ed. Camille Barbagallo (Oakland, CA: AK Press, Forthcoming).

[62]Clinks, ‘Key Facts’, Registered charity, Women’s Breakout: Chances to Change, 2017, http://womensbreakout.org.uk/about-womens-breakout/key-facts/.

[63]MacKinnon, Toward a Feminist Theory of the State, 161.

[64]MacKinnon, 249.

[65] Or to become a very good thief.

[66]Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, trans. Ben Fowkes, vol. 1 (London: Penguin, 1976), 272–73.

[67] As I explain in {Citation}

[68]MacKinnon, Feminism Unmodified, 61.

[69]MacKinnon, Toward a Feminist Theory of the State, 178. I do not suggest that this would be the end of the debate. My point is that MacKinnon’s analysis of gendered subordination should push us to raise this question.

[70] ‘What is your aim in philosophy? To shew the fly the way out of the fly-bottle.’ Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, §309.

Identity and Identity Politics

ISSUE 26(2): IDENTITY POLITICS

Introduction: Identity Is a New Concept

In the attempt to explain and evaluate the late twentieth-century prominence and appeal of identity politics, many have found it useful to historicise their emergence and evolution, thereby revealing that identity was not always central to politics,[1] or demonstrating identity politics to be a recent response to or consequence of other political and economic shifts.[2] In what follows, I will offer a more radically historicist approach; one that offers a fundamental reframing of the issues by drawing our attention not just to the historical specificity of identity politics in advanced capitalism, but to the historical novelty of the very idea of identity itself.[3] To avoid confusion, let me be clear at the outset that the claim I will invite the reader to consider is not that questions of individuality, subjectivity and personhood are in any sense novel – of course, they are not. Rather, I suggest that the widespread refraction of these concerns through the analytical and popular idiom of identity is novel and recent, dating only to the middle of the last century. Beginning from this starting-point, and deploying a cultural-materialist methodology, I trace the evolution of the idea of identity as a category of practice in the social and political contexts of its use in contemporary capitalist societies, demonstrating how the ‘social’ and ‘personal’ senses of identity that now predominate are intrinsically bound up with the social changes that have accompanied them. While these claims about the historical novelty of our current uses of the concept and the word ‘identity’ are challenging, I believe that this perspective is not only well-founded, but also the source of new and fruitful insights about the operations and problems of identity in the twenty-first century.

Let us begin with what will be, in our identity-saturated times, the unsettling point that before the 1950s, almost nobody talked about or was concerned with identity at all. A trawling of popular books and magazines, corporate and business literature and political statements and manifestos published before the middle of the twentieth century reveals no reference to identity as we now know it – there was quite simply no discussion of sexual identity, ethnic identity, political identity, national identity, consumer identity, corporate identity, brand identity, identity crisis, or ‘losing’ or ‘finding’ one’s identity – indeed, no discussion at all of ‘identity’ in any of the ways that are so familiar to us today, and which, in our ordinary and political discussions, we would now find it hard to do without.

The same, startling point holds in relation to the founding figures of sociology and psychology and the giants of the literary canon, whom we imagine to have reflected on questions of identity for centuries. Closer reading of the works of William Shakespeare, Joseph Conrad, Virginia Woolf, George Herbert Mead, Georg Simmel, W.E.B. Du Bois and Sigmund Freud, to take a sample few, reveals the stubborn fact that none of these writers widely credited with discussing or explaining identity ever actually referred to ‘identity’ themselves. Though the term routinely appears in more recent discussions, summaries and reviews of their work, this is typically without any acknowledgement or awareness of the fact that the original authors rarely if ever deployed the term, and never in the manner in which it is used today. (The advent of book digitalisation makes this claim remarkably easy for the sceptical reader to check; and indeed, I have already carried out a painstaking review of works now assumed to be ‘about’ identity, demonstrating that while these writers certainly considered questions of individuality, subjectivity and interpersonal relationships, they did not, contrary to contemporary wisdom, explicitly construe their subject matter as a question of ‘identity’.)[4]