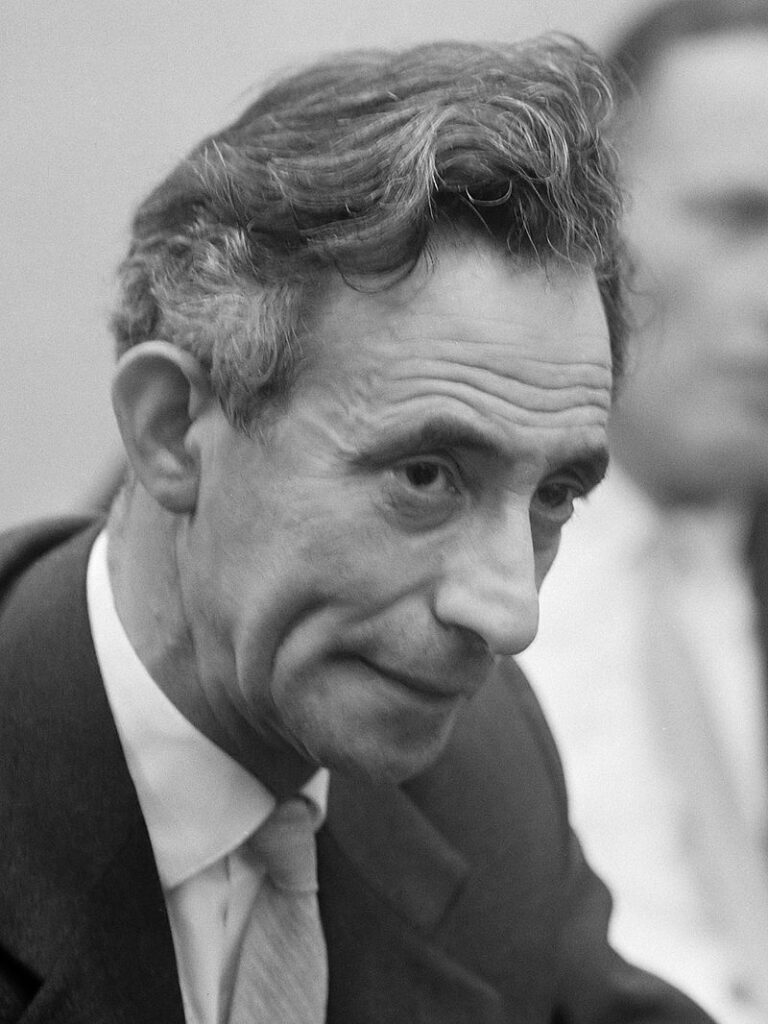

Much of the work of Dutch historian Benjamin Aäron Sijes (1908-1981) revolved around the Second World War. He wrote about the persecution of Roma and Jews by the Nazis, forced labour of Dutch workers during the occupation and the February strike of 1941 that broke out in protest against the anti-Semitic measures of the occupiers.

Sijes grew up in a Jewish proletarian family in Amsterdam, in a ”red” neighbourhood where people had a strong sense of class identity. Many years later, he would still say ”I have no affinity with rich people. Of course, I speak to them, but I do not feel them.” Another crucial part of his personhood was his Jewishness. Especially his grandfather was very religious and orthodox. Sijes would never feel attracted to the religion but his Jewish identity was important for him.

Unlike many people around him, Sijes supported neither the Social-Democratic nor the Communist party, instead gravitating to the council-communist milieu in the thirties. Sijes joined the ‘Group of International Communists’. This group had come to paradoxical conclusions: on the one hand, they were convinced that the working class was capable of spontaneously overthrowing capitalism. On the other hand, they feared that any attempt to organise either economic or political struggles would only give birth to new, bureaucratic elites controlling the workers (as had happened in the Soviet Union), and that any involvement with ”reformist” struggles for social-economic improvements would confuse them.

To avoid this, the GIC limited itself strictly to ideological propaganda and discussion – and refused to organise anything. They never numbered more than a few dozen.

Although not involved in the group, once of its most significant ideological influences was Anton Pannekoek who, under his pseudonym Karl Horner, was attacked by Lenin in his Left-Wing Communism, An Infantile Disorder.

After the war, Sijes became a historian and joined the newly organised Netherlands Institute for War Documentation. In 1960, he wrote a study for use in the trial against Adolf Eichmann. Sijes tried to answer the question how ”dormant material and psychological social forces can lead to unprecedented devastation”. In people like Eichmann, ”a dormant obsession broke loose when during war-time, as obedient servants, they were allowed to do what they had always wanted.”

Sijes also played an important role as an expert-witness in the 1963 trial in Vienna against the Austrian SS-officer Erich Rajakowitsch. Rajakowitsch had been instrumental in the persecution of the Dutch Jews. Rajakowitsch was sentenced to two-and-a-half year of prison – and released after just six months. Still, in 1963, Austria that was a relative success. After that, Sijes was involved in the prosecution of several other Nazi war criminals.

In 1970, Sijes became professor at the University of Amsterdam. In his inaugural lecture, titled ”Some Marxist Concepts Concerning the Conquest of Political Power in the Last Seventy Years”, Sijes showed he still sympathised with council communism and its ideas of the capacity for spontaneous self-organisation by the working class. Some years later, Sijes would prepare Pannekoek’s memoirs for publication. The introductory essay he wrote for it is probably the best summary of Pannekoek’s ideas and life there is.

Sijes’s first book was a study of the February strike, published in 1954. Sijes’s political sympathies could be seen in the attention he paid to the spontaneous aspect of the strike; how workers would convince each other to go on strike and gather more support, without waiting for instructions from any party or union. Still, he was careful to describe the crucial role of the underground Communist Party in laying the groundwork for the strike and spreading it. This was not enough for the post-war leadership of the Dutch CP which combined nationalism with paranoia and delusions of grandeur. It wanted to claim full and exclusive credit for the strike as the birth moment of the ”national resistance”. The party tried to use its press to denounce Sijes as a ”professional anti-Communist”.

But the February strike was not the initiative of a single party, carrying out the orders from its leadership. It was a proud moment of the whole proletarian and socialist milieu in which Sijes had grown up.

As a factory worker at the time, Sijes himself joined the strike. Decades later, he described that day when everybody around him was moved by the idea that they had to show their solidarity with the persecuted Jews, and their resistance against the Nazis:

”We got on our bikes and got the hell out of the factory because we knew that soon the German police would show up, and beat us back into it. Out, out, to the ferries and back to the city. There, on that ferry, that was beautiful, that was one of the most magnificent scenes I have ever witnessed. Those ferries were packed with people and there was singing, the Internationale was being sung. It was truly a great event.”

Sijes wrote that as historian, he attempted to highlight that there are always people who are willing to speak up for others, who are not afraid to tell the truth, and who can not be bought with fame or money. It was a description that also fit himself.

by Alex de Jong