In 1926, Naville wrote a pamphlet seeking to steer the nascent movement of French Surrealists, with which he was associated as one of ‘19 founders’, beyond its spontaneous anarchism and hatred of bourgeois society towards what he saw as a more revolutionary politics grounded in historical materialism and in the “discipline” of working for a party committed, ostensibly (!), to a socialist revolution. Breton welcomed the pamphlet but replied, “All of us Surrealists want a social revolution… but at the same time we want to pursue our experiments in the life of the Mind without any external controls, including controls by Marxists”. The irony behind Naville trying to win the Surrealists to revolutionary politics (that is, to joining the Communist party in France) was, of course, that, just as Breton and Aragon did in fact join the Party, Naville himself was expelled from it for having sided with the Left (or Trotskyist) Opposition in Russia. He was expelled in 1928.

Walter Benjamin wrote a brilliant essay on Surrealism from which it is clear that he was deeply impressed both by the French surrealists and by Naville’s attempt to create unity between them and Marxism. For Benjamin, the crucial point of convergence between these very different strands of thought was Naville’s idea of “organized pessimism”. Here is Michel Löwy’s description of this.

In Benjamin’s view, nothing could be more derisory and idiotic than the optimism of bourgeois parties and social democracy, whose political programme is no more than ‘a bad poem on springtime’. Dismissing this ‘unprincipled, dilettantish optimism’, which is inspired by the ideology of linear progress, he sees in pessimism the effective point of convergence between surrealism and communism. It goes without saying that he is not referring to a contemplative and fatalistic feeling, but to an active, practical and ‘organized’ pessimism that is totally dedicated to preventing, by all means possible, the advent of the worst.

What does the pessimism of the surrealists consist in? Benjamin refers to certain ‘prophecies’ and to Apollinaire and Aragon’s premonitions of the atrocities to come: ‘Publishing houses are stormed, books of poems thrown on the fire, poets lynched.’ The impressive thing about this passage is not only the accurate premonition of an event that was indeed to occur six years later when the Nazis made bonfires of ‘anti-German’ books in 1934; we have only to insert the words ‘by Jewish (or anti-fascist) authors’ after ‘books of poems’ – but also and above all the expression used by Benjamin (it does not appear in either Apollinaire or Aragon) to describe these atrocities: ‘a pogrom of poets’. Is he talking about poets or Jews? Or are both threatened by this disturbing future? As we shall see later, this is not the only strange ‘premonition’ to be found in this surprisingly rich text.

One wonders, on the other hand, what can be meant by the concept of pessimism as applied to the communists; after all, their doctrine of 1928, which celebrates the triumphs of the building of socialism in the USSR and the imminent collapse of capitalism, is a fine example of the optimistic illusion. Benjamin in fact borrows the concept of the ‘organization of pessimism’ from an essay he describes as ‘excellent’, namely Pierre Naville’s La Revolution et les intellectuels (1926). A close collaborator of the surrealists (he was one of the editors ofLa Révolution surréaliste), Naville had recently opted for political commitment to the communist movement and wanted his friends to follow his example. […]

According to Naville, pessimism is surrealism’s greatest virtue, both in terms of its current reality and, even more, its future developments. In his view, pessimism is rooted in ‘the reasons that any conscious man can find for not conforming, especially morally, with his contemporaries’, and it constitutes ‘the source of Marx’s revolutionary method’. Pessimism is the only way ‘to escape the incompetence and disappointments of an era of compromise’. [Naville] concludes: ‘we must organize pessimism.’ The ‘organization of pessimism’ is the only slogan that can save us from death. Needless to say, this impassioned apologia for pessimism was far from representative of the political culture of French communism at this time. Before long, Pierre Naville was expelled from the Party: the logic of his anti-optimism led him to join the ranks of the left (‘Trotskyist’) opposition, and he became one of its most important leaders. The positive reference to Naville and to Trotsky himself in Benjamin’s article … at a time when the founder of the Red Army had already been expelled from the CPSU and exiled to Alma Ata, is a good example of his independence of mind.”

Later in his long life, Naville went on to become a major ‘sociologist of work’, with a massive study of automation that was published in 1961. I interviewed him in Paris in 1986, but he spoke so fast that much of what he said about the unions and the French working class went over my head. I regret not having taped that interview. Unlike the contemporaneous American optimism about automation, Naville argued that ‘Automation induces the final rupture between the producer and the product. It deprives the worker of any contact with the raw material’, destroying any residual sense of a personal relationship with the machine. ‘He (the worker) feels that this machine is not really his.’ And Naville suggested that ‘work in the highly automated plant is frequently boring, lonely, and mentally stressful’. Automation increased mobility between jobs and encouraged companies to impose the kind of flexibility that destroyed “the worker’s sense of having a distinctive occupational identity”. Finally, Naville felt that automation would both increase conflict with management and bring about the development of new and distinctive patterns of conflict in industry, a thesis that clearly foreshadowed Serge Mallet’s own arguments. (For a concise summary of their views, see Gallie, In Search of the New Working Class, pp.21ff.).

Both Naville and Mallet were part of the left wing of the French Socialist Party (the PSU) and obviously knew each other well. For Löwy’s essay on Benjamin and Naville, see https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/walter-benjamin-and-surrealism

By Jairus Banaji

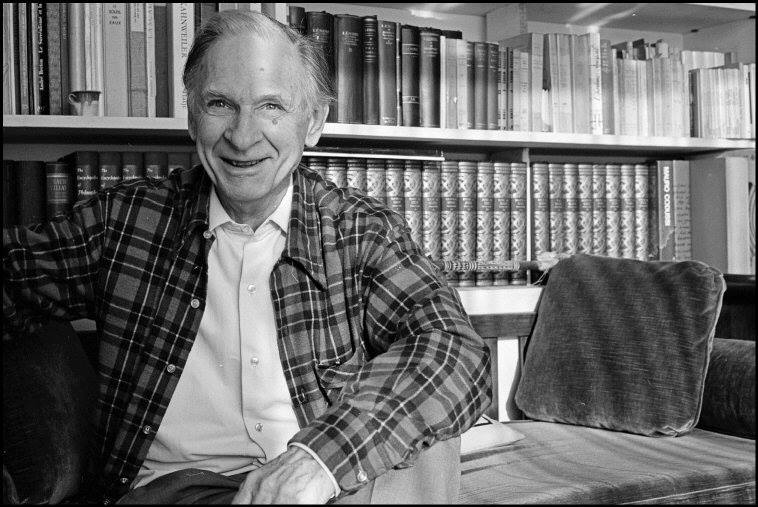

Photo caption: Pierre Naville (1903–1993) at his home in Montparnasse