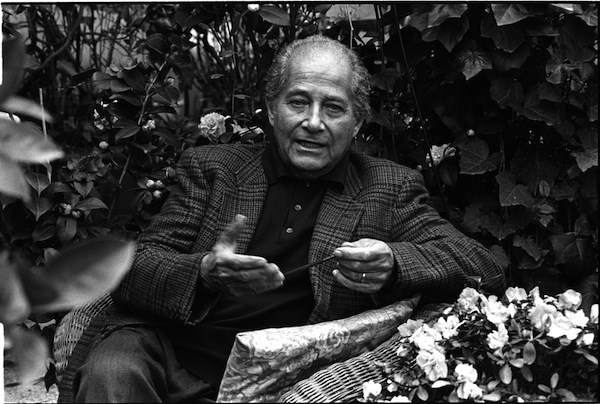

Gillo Pontecorvo (1919–2006), whose masterpiece “The Battle of Algiers” (1966) remains the most perfect example of a ‘reconstructed realism’, the purest cinematic equivalent of Marx’s famous metaphor of the ‘life of the subject-matter’ being ‘ideally reflected as in a mirror’ (1873 Afterword to Capital, vol. 1). What Pontecorvo set out to do was, in his words, ‘represent the irreversibility of a revolutionary process when a colonized people acquires consciousness of its identity as a nation’. And he did this so well that the film was boycotted by the French delegation at the Venice Film Festival in 1966 and banned for over three years in both France and England (till 1971).

This was history in the Hegelian style, reduced to its essential elements yet retaining the cineaste’s reverence for ‘form’, for the way those elements ‘appear’, the way they are ‘represented’ to the viewer. “Battle” is a chronicle of the Algerian Revolution or, more correctly, of the urban side of it, shot in black & white, in locations where the struggle actually took place, in streets too narrow for use of the dolly, shot entirely with non-professional actors (save for the French theatre actor Jean Martin who acts as the clinical Colonel Mathieu), and made with a single, hand-held camera. It was based on six months of intensive research plus another six months of script writing (cf. Marx’s distinction in the Afterword between research and the ‘presentation’ of its results), and it showed audiences the potential contained in fusing a mesmerizing Neorealism with revolutionary politics.

Pontecorvo’s whole formation as a Marxist (‘After the war I went into politics, working full time for the Italian Communist Party, until 1956 when I quit’) showed the kind of flexibility and breadth of character where Umberto Barbaro (Marxist film theoretician), Lukács and Fanon were as central to his perspectives as Eisenstein or Rossellini. The stark juxtapositions that run through the narrative are like an extended commentary on one unforgettable passage in Wretched of the Earth where Fanon contrasts the settlers’ town (The settlers’ town is a strongly built town, all made of stone and steel. It is a brightly lit town; the streets are covered with asphalt…) with the town of the natives (‘the village of the blacks, the medina, the reservation’, in Algiers the Casbah), except that the Casbah in Pontecorvo is no ‘town on its knees’ but the precise base of an urban guerrilla war targeting the colonial state in the very heart of Algiers’ European city.

Although “Battle” was frequently criticised for its alleged defects (for projecting a false ‘equality of violence’; overlooking the struggle in the countryside; failing to prefigure the problems that would beset independent Algeria; and so on), as a work of art, it had no obvious parallel. The best technical analysis of the film (by Joan Mellen in the Filmguide series) notes Pontecorvo’s ‘brilliant use of sound’, his foreshortening of time to convey a compressed or essential history of the struggle (choosing ‘episodes that could function as typical examples of the events between 1954 and 1957’), a style of camera work perfectly adapted to the rhythms of a mass struggle, a camera that ‘moves in and out of the action as quickly as the F.L.N. emerge and retreat from their hiding places in the Casbah’, actors chosen on the basis of physical appearance alone, images that convey the same ‘quality of truth’ as newsreel footage on the 9 o’clock news with a complete avoidance of any actual news footage, whole sequences of remarkable virtuosity constructed to communicate the tension of this armed struggle (such as an ‘intense, high-speed account of police assassinations all over Algeria’ early in the film or the sealing of the Arab quarters when mass repression starts), and so on.

An American critic wrote in 1973 that Pontecorvo was ‘the most dangerous kind of Marxist … a Marxist poet’. She claimed that “Battle” was ‘perhaps the only film capable of convincing [even] a bourgeois public of the need for revolutionary violence’ (Kael, The New Yorker, 9 Nov. 1973). Yet Pontecorvo, as Mellen argues, ‘condemns all human suffering … and suggests that terror committed against the innocent, no matter under what flag, undermines the cause in whose name it is deployed’. ‘Torture was the official policy of General Massu (Mathieu in the film) and his paras in Algeria’, and Pontecorvo made it the permanent counterpoint of the terrorism the FLN chose as their trigger to a wider mass involvement. Finally, in his 1974Cinéaste interview, Pontecorvo described colonialism as ‘the matrix of all our culture’. ‘Even if we speak about colonies of other people, it is connected with our life in Italy’.

The whole of this brilliant film can be watched here, all 2 hours of it;

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f_N2wyq7fCE

Jairus Banaji